America's Big Tariff Debate Explained

Are tariffs good or bad for America?

Donald Trump calls it the most beautiful word in the dictionary, while Kamala Harris says it’s a national sales tax that hurts ordinary Americans.

I’m, of course, talking about tariffs— a policy measure that has become a defining issue in the U.S. presidential election. So, who’s right about tariffs, Trump or Harris? That’s the question that I’m going to try to answer in this post.

Now, we know Trump loves tariffs, but he didn’t just start embracing them out of the blue.

For decades, he’s been touting tariffs as the solution to what he sees as a major problem— the idea that other countries are ripping off the U.S.

Well before he walked down the golden escalator at Trump Tower and announced his bid to become president in 2015, Trump was making this claim.

Here’s a clip of Trump talking to Larry King about it all the way back in 1987.

So, this has been a core issue for Trump for decades, and it was one of the key pillars of his platform leading up to the 2016 election.

The only difference is, instead of focusing on Japan and Saudi Arabia like he did in the 1980s, more recently, he’s been focused on China.

In early 2016, Trump went as far as to say that China was raping the U.S., and that he would fix the problem with tariffs.

That message seemed to resonate with a lot of voters, and might have played a pivotal role in shifting enough votes in the Midwestern swing states to win him the election.

Fast forward eight years and Trump is at it once again. He’s using exactly the same playbook, accusing China of acting unfairly when it comes to trade, and promising to respond with much higher tariffs.

I’m writing this post on November 4th— a day ahead of the 2024 election. You might be reading this either before or after the results are known.

But regardless of whether Trump wins or not, it’s worth exploring what higher tariffs mean for the economy, especially since this isn’t just a Trump issue.

One of the biggest legacies of the first Trump administration is that it changed the norms surrounding trade and tariffs.

As I’ll discuss, Trump upended a century of U.S. trade policy, and we’re still feeling the repercussions of that today.

His successor, President Biden, has retained and expanded on the Trump tariffs, and we’re likely to see more tariffs in the future, regardless of who wins the election.

So, lets talk about this very important issue, starting right at the top:

What are tariffs?

Well, if you’re not aware, a tariff is simply a tax on goods imported from other countries. Like other taxes, they raise money for the government, which the government can then spend on whatever it wants to spend it on.

Tariffs can also be used to protect certain industries from foreign competition and to incentivize certain behaviors.

So, tariffs have two broad functions: they’re a revenue source for the government and they protect domestic industries.

Today, tariffs are mostly used for protectionist purposes. They’re a very insignificant source of government revenue, making up just 2% of total federal tax revenue.

But that wasn’t always the case. In the century after the U.S. became an independent nation, tariffs made up the majority of the federal government’s tax revenue.

You see, tariffs have a long and tumultuous history in the U.S., with the Cato Institute calling them “the most contentious federal policy issue of the 19th century” outside of slavery.

Proponents of tariffs, like Alexander Hamilton, believed that they were a good source of government revenue and helped U.S. industries— especially those that were in their early stages— to flourish.

On the other hand, opponents of tariffs, like Thomas Jefferson, said that they distorted the free market and led to lobbying and corruption as businesses tried to game the system by getting the government to impose tariffs on their foreign competitors.

For many decades, the U.S. went back and forth from periods of very high tariffs to periods of somewhat lower tariffs.

A big moment came in 1913, when public opinion sharply turned against tariffs due to the rampant corruption associated with them and a growing awareness that they disproportionately hurt people with lower incomes.

The only problem was that the government still needed revenue to fund itself. So, what did it do?

It imposed a federal income tax, which was made possible by the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment that same year. With the income tax funding the government, tariffs were lowered dramatically— at least, at first.

The thing is, while the government no longer depended on tariffs as a revenue source, it didn’t stop a lot of people and businesses from advocating for them.

In fact, with income taxes now making up the bulk of the government’s revenue, tariffs no longer needed to be restrained.

Remember: in the early days of the U.S., the two goals of tariffs— a means to raise government revenue and way to protect industries— were often at odds with each other.

In order to protect industries, tariffs needed to be high enough to discourage consumers from buying foreign products. But if they were too high, imports would decline dramatically, hurting the government’s ability to collect revenue by taxing the imports.

But after 1913, when the government started getting most of its revenue from the income tax, that was no longer the case.

The introduction of the income tax removed one of the main functions of tariffs, leaving them as solely a protectionist tool.

When the economy crashed during the Great Depression, Congress used this tool in a big way, hoping that it would help end the depression and turn the economy around.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 raised tariff rates to more than 59%, the second highest level on record.

But rather than help the economy, the tariffs exacerbated the downturn as America’s trading partners retaliated against the tariffs by imposing tariffs of their own, which hurt U.S. exporters.

Once it became clear how disastrous the Smoot-Hawley tariffs were for the economy, tariffs once again fell out of favor— and this time, the shift away from tariffs would last for a long time.

In 1934, the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) was passed, which took the power of the tariff from Congress and put it in the hands of the president.

With the RTAA, the president could negotiate tariff reductions directly with other countries, benefiting both the U.S. and its trading partners.

Around two decades after the RTAA came the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), a pact between dozens of countries to lower tariffs and other trade barriers.

The GATT eventually led to the formation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, which now serves as the primary international body overseeing global trade rules and resolving trade disputes among nations.

That, in a nutshell, is the history of tariffs in the U.S.

We went from tariffs being the primary source of government revenue and a tool to protect certain domestic industries, to them being used just as a protectionist tool after the establishment of the income tax.

Then we went through a long period of trade liberalization, where tariffs were cut substantially.

Over the past century, that has been the trend; tariffs have been going down. From a high of 59% in 1932, average tariff rates in the U.S. fell as low as 4% in 2008— and that’s generally been a good thing for the U.S. economy.

You see, there’s this concept in economics called comparative advantage, and it says that countries benefit by specializing in the production of goods they can make the most efficiently, then trading with others for the rest.

That’s the allure of free trade: trade without tariffs or any other restrictions leads to the greatest amount of prosperity because countries can focus on their strengths.

But even though free trade is optimal in a perfect world, we don’t live in a perfect world.

Tariffs are still being used— sometimes rightly and sometimes wrongly.

Under WTO rules, tariffs are allowed to protect against dumping— a situation in which a country sells goods to another country at prices below the cost of producing those goods in an effort to gain market share.

They can also be used in cases where unfair subsidies are used to produce goods.

The Trump Tariffs

That brings us full circle back to Trump. These are the types of things that Trump claims that China has been doing; and as I talked about earlier, he promised to fix the situation by using tariffs.

In 2018 and 2019, Trump followed through on his threat by putting tariffs on $380 billion worth of goods, mostly from China but from other countries as well.

And now with the benefit of hindsight, we can see the impact that Trump’s tariffs have had, and whether he was successful or not in achieving what he wanted to do.

Generally speaking, studies have shown that Trump’s tariffs haven’t had the impact that he hoped they would have.

To understand why, first, let’s briefly recap how tariffs work.

A tariff is paid to the government by the company importing the foreign good. Sometimes the foreign company selling the good lowers the price of their product to fully or partially offset the tariff.

Other times, the cost of the tariff is absorbed by the U.S. company that imports the product.

But most commonly, the tariff is passed on to the end consumer of the product— either other companies or individuals like you and me.

Let’s take the example of the government putting tariffs on washing machines.

If Walmart imports washing machines from China, it pays the government a tariff on those imports; that’s an additional cost for Walmart.

The washing machine manufacturer in China might lower the price it charges Walmart to help offset the tariff.

But if the Chinese company is already selling its washing machines at a low price, it might not be able or be willing to lower the price further.

In that case, Walmart could either eat the cost, reducing its profits, or more likely, pass the higher cost along to consumers by raising the retail price of the washing machines.

Here’s a great chart from Justin Wolfers, economics professor at the University of Michigan, which shows what happened when the Trump administration actually put tariffs on foreign washing machines back in 2018.

Right after the tariff hike, prices for washing machines went up significantly, much more than the prices for other appliances which weren’t hit by tariffs.

Then, when the tariffs expired in early 2023 under the Biden administration, prices for washing machines fell significantly, dropping much more than the prices for other appliances.

This is a real-life illustration of the fact that most tariff increases are ultimately passed on to the end customer; studies show this over and over again.

Some might argue, though, that maybe that’s acceptable. If tariff increases encourage companies to manufacture goods in the U.S. and hire workers in the U.S. rather than importing foreign products made with foreign labor, perhaps they’re worth the pain of higher prices.

Unfortunately, most studies also show that the Trump tariffs weren’t very effective at jumpstarting industries or creating jobs.

Here’s a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research which explains that the tariffs didn’t raise employment in the industries that were protected by the tariffs.

Even worse, other countries retaliated against the U.S. tariffs by targeting U.S. exports with their own tariffs. This, in turn, had “clear negative employment impacts, primarily in [the] agriculture [industry].”

So, as you can see, there are a lot of issues with tariffs.

They make products more expensive for consumers, and because they hit people with lower incomes the hardest, they are considered a regressive tax.

Additionally, tariffs usually lead to retaliation by other countries, which hurts American exporters. These exporters are also hurt by the higher prices they have to pay for the imported goods that they use in their production processes.

For instance, you could raise tariffs on imported steel, benefiting the U.S. steel industry. But that in turn hurts the much larger U.S. auto industry, which now has to pay higher prices for steel.

The problems don’t stop there.

Pitts Enterprises vs CIE Manufacturing

Bloomberg wrote a great story about what really happens on the ground when the U.S. puts tariffs on China.

The story centers on two companies in rural towns— one in Alabama and one in Virginia— that built trailer chassis, the thing that trucks use to transport shipping containers over roads.

In 2020, the Alabama company, Pitts Enterprises, was really struggling to survive because of intense competition from a Chinese company called China International Marine Containers Group.

This company was absolutely dominating the market, pushing Pitts to the brink.

But Pitts argued that the Chinese company wasn’t competing fairly, that it was being subsidized with cheap steel and electricity by the Chinese government— and Pitts just couldn’t compete with that.

After conducting an investigation, the U.S. government agreed with Pitts and in response, put tariffs of 220% on Chinese trailers, increasing their price by 3.5x.

All of a sudden, Pitts was back on track and business starting to take off again thanks to the tariffs.

But the Chinese company didn’t give up. They already had a small presence in Virginia; so, after the tariffs went into effect, they expanded that significantly.

They created subsidiary called CIE Manufacturing and invested $20 million into the Virginia operations to build trailers without any Chinese parts.

Things were going well: they hired 400 people, sales were strong, and they were happy.

That is, until they discovered something really fishy.

CIE claims that Pitts— their Alabama competitor who had gotten the government to put tariffs on Chinese chassis— was importing thousands of trailers from Vietnam, and that these trailers were being made with Chinese steel (meaning that they should be subject to the same tariffs that CIE’s parent Chinese company was subject to).

So, another investigation ensued and the U.S. government ended up agreeing with CIE. As a result, they put tariffs on Pitts.

The story didn’t end there. Pitts shot back by accusing CIE of importing Chinese-made trailers through Thailand.

This time, though, the investigation didn’t turn up anything nefarious, and the government ended up clearing CIE of any wrongdoing.

But the damage had already been done. The company had laid off most of its 400 employees and drastically scaled back its operations in Virginia.

As for Pitts, it’s still being investigated by the government and it continues to deny any wrongdoing.

Skirting Tariffs

So, this saga is a great illustration of the difficulty of fixing trade issues with tariffs.

You have a well-intentioned solution (tariffs) to a legitimate problem (China dumping goods into the U.S. at below cost), but it turns out to be extremely messy when put into practice.

It kind of brings us back to what I was talking about earlier in this post about how in the early days of the U.S., tariffs would lead to lobbying and corruption as companies tried to use the government to hurt their competitors.

I mean, even in cases where there’s nothing illegal or shady going on, companies have every incentive to try to skirt tariffs by shifting their operations to countries that aren’t affected by them.

One of the big goals of the Trump tariffs was to bring manufacturing industries back to the U.S., but as I said earlier, the tariffs haven’t done a great job of doing that.

Instead, we’ve seen production shift to other countries, like Mexico and Vietnam. And in many cases, it’s Chinese companies themselves setting up shop in those countries to export their goods under the radar.

The China Shock

So, what’s the solution to that? Because some of the issues that Trump has rightly pointed out over the years haven’t gone away.

In fact, there is now broad agreement that ever since it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has been, at least to some extent, abusing the global trading system; for instance, by giving massive subsidies to its companies— some of which are owned by the government— and by stealing American intellectual property.

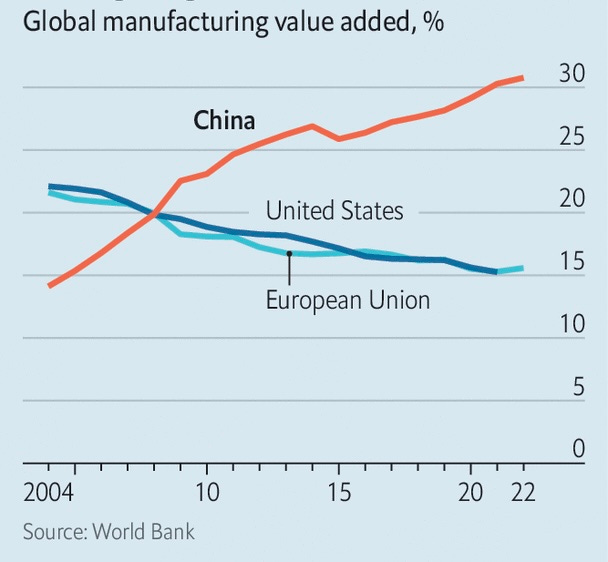

China’s controversial trade policies have contributed to it becoming a manufacturing powerhouse. But that’s taken place at the expense of America’s manufacturing industry, which has seen a steep decline in the same period.

This is known as the “China shock,” and it led to millions of job losses in the U.S., particularly in the Midwest and Southeast of the country.

And now, some, like Brad Setser, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, argue that we are in the midst of a second China shock.

This time, China is subsidizing key industries of the future with the intention of dominating them. It’s already become the global leader in electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels. And it’s flooding the world with these products.

This is problematic— not just because it’s difficult for companies in other countries to compete with Chinese companies that are heavily subsidized by the Chinese government, but because there are national security implications.

China is an adversary of the U.S., so being so dependent on the country for key goods could be seen as a national security risk.

Ever since the Covid pandemic, it’s also become abundantly clear that there are supply chain risks from relying heavily on a single country for critical goods.

So, as wonderful as international trade is for economic growth, perhaps there’s a limit to how “free” trade can be.

Sometimes there are other countries who aren’t playing by the rules; sometimes there are national security risks; and then there are supply chain risks as well.

But again, what is the solution to the problem?

Well, different people have different views on that.

Solutions

Obviously, you have Trump, who favors very high, across-the-board tariffs. But as I discussed, that approach hasn’t been all that effective.

You also have the approach taken by the Biden administration, which combines targeted tariffs and other trade restrictions with industrial policy.

During his term, Biden has kept most of the Trump tariffs in place, while adding additional tariffs on $18 billion worth of Chinese goods.

Notably, he raised tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles to a whopping 100%, effectively cutting them out of the U.S. market.

Additionally, Biden has put restrictions on the sale of critical components— like advanced semiconductors— to China, in an effort to ensure that the U.S. stays ahead of its rival when it comes to the development of cutting-edge technologies like AI.

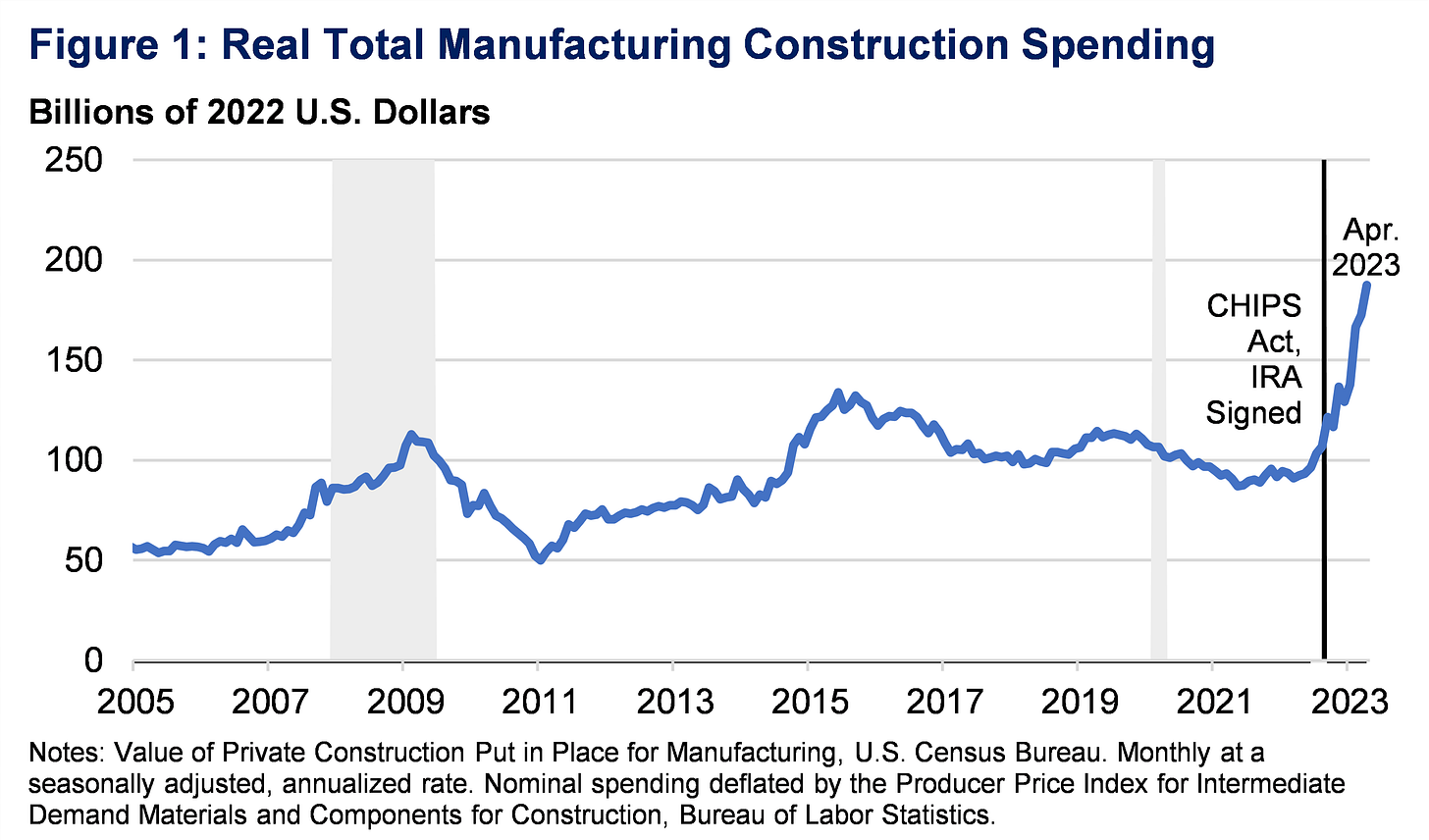

Biden has also helped pass bills like the CHIPS And Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act that provide funding for companies to produce key goods in the U.S.

And if that sounds familiar, it should— that's what China is doing: providing support to key industries. So, industrial policy in the U.S. is essentially a way to match what China is doing.

From what we’ve seen so far, these policies have had an impact in a way that tariffs haven’t. Construction spending on manufacturing facilities in the U.S., for instance, has surged over the past few years to levels we haven’t seen in decades.

That said, not everyone supports these policies. Some believe that industrial policies face the same flaws as tariffs and other heavy-handed government interventions, with the potential for wasteful spending and resources being used inefficiently.

Related to this is another view that says that instead of using industrial policy, tariffs or any other sort of government intervention in the markets, the U.S. should double down on free trade.

Henry Gao, a professor at Singapore Management University, makes this argument. He says that China’s economic model is unsustainable and that the U.S. shouldn’t try to replicate it with industrial policy.

Instead, the U.S. should advocate for free trade and work to reduce trade barriers through the World Trade Organization and by creating multilateral trade agreements with other countries.

He sums up his main point by saying, “if you try to compete with China by becoming China, what is the point even if you win in the end?”

As you can see, there are a wide range of views on how to approach international trade— particularly with China— in today’s world.

Tariffs are one tool being proposed, but there are many others as well.

What Happens Next

So, we’ll see what happens.

If Kamala Harris wins the election, we’ll probably see a continuation of Biden’s approach.

On the other hand, a second Trump administration would likely lean much more heavily on tariffs.

Trump has said in a second term, he would push for tariffs of at least 20% on all imports, while hiking tariffs on Chinese imports to 60%.

According to the Tax Foundation, this would push the average tariff rate in the U.S. to the highest level since the Great Depression.

Trump has even gone as far as to float the idea of abolishing the income tax and replacing it with tariffs, taking the U.S. back to the type of tax regime that existed prior to 1913, as I discussed as the beginning of this post.

But that type of situation is a pipedream is the current environment. There is almost no way for tariffs to replace income taxes; the math simply doesn’t add up.

I think a lot of these really aggressive tariff proposals from Trump stem from his mercantilist worldview— his belief that a country can only be wealthy if it exports more than it imports.

But that type of thinking is a relic of the distant past. A country’s trade balance in and of itself has no bearing on its wealth. Maybe I’ll write another post on that in the future.

I hope you learned something about how tariffs work and what the whole debate surrounding them is about from this post. Thanks for reading and remember to vote on Tuesday if you haven’t already!

Excellent writing & well researched!

Very balanced take on the situation. Great write up there.

Trump has won as I type this so hope he looks at the bigger picture while taking any decisions!