Everything You Know About How Money Is Created Is Wrong

If you’re like most people, you probably think that money is created by the government. But that’s only partially true.

Everything you know about where money comes from is wrong.

If you’re like most people, you probably think that money is created by the government.

But that’s only partially true. In modern, developed economies like the U.S. and the U.K., less than 10% of what we call money is created by the government—specifically central banks.

The rest is created by private banks.

Yes, the banks you keep your money with—like Chase, Bank of America and Barclays—create most of our money.

They do this every time they make a loan.

For instance, say you want to buy a house, so you take out a mortgage with your local bank. The money that the bank gives you is created out of thin air.

This is a key point that a lot of people don’t understand. Even many introductory economic textbooks erroneously claim that banks lend out the money that people put into their checking and savings accounts.

Based on that, banks can only lend out the money that already exists and is deposited with them.

But that’s not correct. Banks can lend out as much money as they want, and all their loans are made up of money that they create.

At this point, you’re probably thinking: if this is true, what’s stopping a bank from creating an unlimited amount of money and enriching itself and all its executives in the process?

Let’s talk about why that doesn’t happen.

The first thing you need to understand is that there are a few different types of money. To us, money is money, but it turns out that not all money is the same.

One type of money is the type I’ve been talking about—deposit money. This is the money you see in your bank account. It’s completely digital and only exists as numbers in a database maintained by your bank.

But there are other types of money as well, like physical currency, which everyone is familiar with; and something called reserves, which is money held by private banks at a country’s central bank (for instance, money held at the Federal Reserve by Wells Fargo or at the Bank of England by Barclays).

Together, physical currency and reserves are called central bank money because they’re both created by central banks.

So, how does this all tie together?

Well, as I said, banks create deposit money through lending. But after they make a loan, that money doesn’t necessarily stay with the bank that made the loan.

If you take out a mortgage from your local bank, the bank gives you money and then you pay that money to the seller of the house that you purchased.

The money then ends up in the seller’s bank—and there’s a good chance that the seller’s bank is different from your bank.

As a result, your bank will have to send money to the seller’s bank.

How do banks send money to each other? By transferring the reserves that they keep at the central bank.

The central bank acts like a banker for private banks, allowing them to send money back and forth to each other.

Banks can only create “deposit money;” they can’t create central bank money, which is what they need to send money to other banks.

The fact that money flows in and out of individual banks is a constraint on the amount of money that banks are willing to lend because they need a certain amount of central bank money on hand to send to other banks during the course of normal business operations.

Every day, customers of some banks are sending money to customers of other banks and money is flowing in and out of all of these banks. Central bank money what they use to transfer funds to each other.

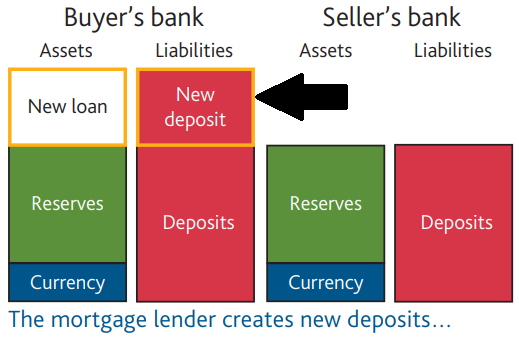

This might make more sense if we look at it visually. These are the balance sheets of two banks involved in the purchase of a house.

Both the bank of the homebuyer and the bank of the home seller start with a combination of reserves and currency, which together are central bank money. Those are the banks’ assets.

On the other side of the ledger are the deposits that customers hold in their accounts. To us, that’s money—it’s an asset— but to the banks, it’s a liability. They owe us that money.

Now let’s look at step two. Your bank gives you a mortgage, so it credits your account by the amount of the loan. Your checking account balance goes up, which again, to the bank, is like an increase in its liabilities.

While the mortgage itself is an asset for the bank, which it expects to be repaid with interest.

You can see that when your bank gives you a mortgage, money is created out of thin air. This new money in your account didn’t exist before you got the mortgage.

In step three, you take the money your bank lent you and you send it to the home seller.

If the homer seller uses the same bank as you, the bank could just transfer some of the deposits in your account to the home seller’s account and it wouldn’t have to do anything else; it would just be moving number around internally within its own database.

But more likely, the home seller uses a different bank, so your bank has to make a bank-to-bank transfer using central bank money. That reduces your bank’s reserves and increases the reserves at the home seller’s bank.

Additionally, the seller’s bank credits their account with new deposits.

If you compare the first chart I showed to the last chart I showed, you can see that the total amount of money did increase by the amount of the mortgage loan.

But your bank’s reserves went down a lot, which reduces the amount of money it can lend in the future, while the home seller’s bank’s reserves went up, which increases the amount it can lend.

As you can see, a bank need reserves on hand in case customers take money out of the bank, and that limits the amount of loans any individual bank can make, and thus the amount of money they can create.

The good news is that reserves are almost always available to banks—at the right price.

There are a couple of ways they can get them.

They can try to get customers to add more money into their accounts (“steal” reserves from other banks). Just like we saw in the example with the mortgage— when the home seller got paid for their house, that inflow of money resulted in the seller’s bank getting more reserves.

Another way a bank could get reserves is by borrowing them, either from other banks or the central bank itself. When it does this, it has to pay an interest rate—and in fact, this interest rate is the way in which modern central banks conduct monetary policy.

By setting the interest rate banks pay to borrow reserves, the central bank can influence how much lending and money creation happens in the economy.

When banks can borrow reserves at a low interest rate, they’re more likely to be able to make loans profitably. There will also be more demand for loans from businesses.

The opposite is true as well. When interest rates on reserves are high, you’re going to see less lending and money creation.

So there you have it. Banks create money but the amount of money any individual bank can create is limited by access to funds called reserves. These reserves are readily available at a price set by central banks.

And finally, here’s a cool corollary to the fact that banks create money by lending. When you repay a loan—and that includes when you repay your credit card balance—you’re destroying money. That money no longer exists in the economy.

Pretty cool, right?