FedNow Explained

People are worried about a new government service that is launching next month.

People are worried about a new government service that’s launching next month.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who is challenging Joe Biden to be the Democratic Party's nominee in the upcoming presidential election, recently tweeted that the “Fed Now Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)” that is launching in July will “grease the slippery slope to financial slavery and political tyranny.”

If you do a search for FedNow on TikTok or on YouTube, you’ll see a lot of this same type of talk: concern that the U.S. federal government is doing something nefarious with FedNow— that it’s going to either invade your privacy or worse, steal your money.

Should you be worried? Let’s discuss.

The first thing to note is that FedNow isn’t something that the government sprung on us out of the blue. It’s been in development since 2019.

That said, yes, it is going to launch next month.

But contrary to what some people are saying, FedNow has absolutely nothing to do with central bank digital currencies, or CBDCs.

Rather, FedNow is a new system that helps money move from those making payments to those receiving them.

Think about all the ways in which you make payments today, starting with cash.

You can take a five-dollar bill and hand it to the cashier at McDonalds and boom— money has been moved.

Cash is a unique type of money. It’s a bearer asset. If you hold cash in your physical possession, you own it. There’s no official record of who owns how much cash.

That’s different from other types of money, like bank deposits, where some entity—like your bank—keeps a record of who has how much money.

Most of the money we use today is like that; it’s either in a bank like Chase or in a digital wallet like PayPal. And those companies keep track of how much money we own.

But what if we want to send the money in our bank accounts or in our digital wallets to someone else?

It’s obviously not like cash, where we physically hand someone a piece of paper to transfer ownership.

Instead, someone has to update the record of who owns the money. If I send you money from my PayPal account to your PayPal account, then it’s PayPal who updates its records to reflect that the money has gone from me to you.

It’s the same situation if I want to send money from my Wells Fargo bank account to your Wells Fargo bank account. That company, Wells Fargo, updates its records to reflect the payment.

But what if I want to send money from my Wells Fargo account to your Bank of America account?

In the previous example I just gave, both my money and your money were sitting in Wells Fargo, so when I sent you money, the bank could just update its records to show that I had less money, and you had more money.

But when you add Bank of America to the mix, things start to get a little more complicated.

In this case, the money is in my account at Wells Fargo, but I want to send it off to your account at Bank of America. How does it get from here to there?

Well, it happens through an interbank transfer. This is when money is transferred from one bank to another, usually electronically.

You see, just like we hold our money at banks and those banks keep a record of how much money we own, those banks hold money at the U.S. central bank—the Federal Reserve—and the Fed keeps a record of how much money those banks own.

So, when I, as a customer of Wells Fargo, send money to you, a customer of Bank of America, the Fed updates its records to show that money went from Wells Fargo to Bank of America.

At the same time, Wells Fargo updates its records to show that I have less money in my bank account and Bank of America updates its records to show that you have more money in your bank account.

That’s how money moves from bank to bank, but it doesn’t just magically happen. There are systems in place to orchestrate this—some are run by private companies, and some are run by the Fed.

Most interbank transfers today happen through systems like the Automated Clearing House (ACH) and wire transfers.

If your employer pays you by depositing money into your bank account or you pay your utility bill by transferring money out of your bank account, those payments are most likely taking place using the ACH system.

The way ACH works is if you want to make a payment, your bank creates an electronic file with payment information in it—things like routing numbers, customer account numbers, the amount of money to be transferred, etc.

And then it sends the file off to one of two ACH network operators—either the Fed or a private competitor called the Electronic Payments Network (EPN).

The ACH network operator then looks through that file, as well as all the other files it received on a particular day, nets all the payments, and determines how much money each bank owes or is owed.

Then based on that, the Fed moves money from banks that owe money to banks that are owed money.

Wire transfers are even simpler. When you want to send a wire, your bank simply takes the payment instructions from you and sends them to the Fed, which transfers the money from your bank to the bank of whoever you’re sending money to.

ACH payments are slower but cheaper, while wires are faster but more expensive.

That brings us to FedNow.

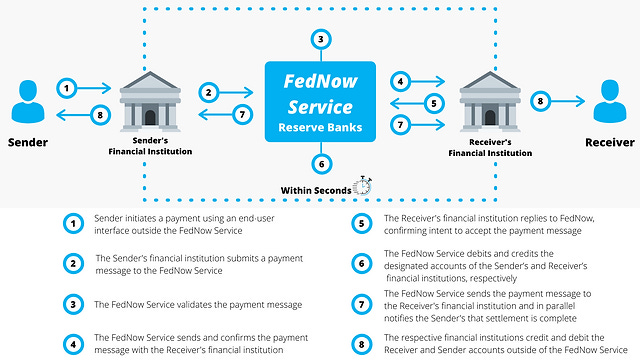

FedNow is just another system for transferring money from bank to bank.

Banks will send payment instructions to the FedNow service, and the FedNow service will facilitate the movement of money from one bank to another.

But unlike ACH and wires, which have been around for decades, FedNow is a completely modern system that is designed to transfer money instantly, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

That means you can initiate a FedNow transfer anytime, and money received with FedNow can be used immediately.

By comparison, ACH payments and wire transfers are only available on weekdays during business hours, and it can take anywhere from a few hours to a few days to send and receive money through those systems.

With FedNow, payments are instant and extremely cheap—only $0.045 per transaction.

There are obvious benefits to that. If you work at a job and you get paid through FedNow, you’ll be able to spend your money as soon as your employer pays you. You don’t have to wait around a few days for the payment to clear like you would with a direct deposit that goes through the ACH system.

By the same token, if you want to send money quickly (maybe to make a last-minute payment on a loan), you can do that without worrying about missing the deadline for that payment.

So, these are all benefits of instant payments and they’ll be useful for a lot of people, but maybe not everyone.

Some people might not need instant payments. Getting your money a few days after someone pays you might not be a big deal for you.

And even if you want your money faster, you might already use apps and services like PayPal, Venmo, Cash App and Zelle, which allow you to receive and send money in a way that seems instant.

As I mentioned earlier, if you transfer money from one PayPal account to another, that transaction happens instantly because the only thing PayPal needs to do is update its records of who owns how much money.

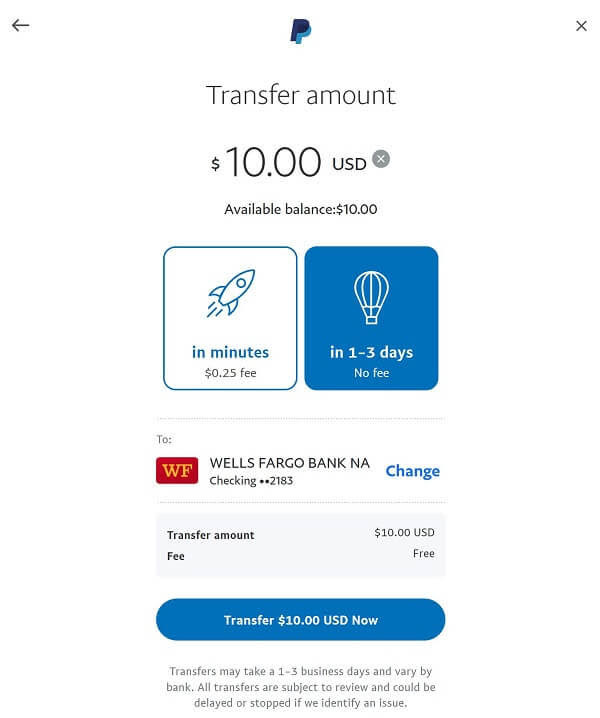

It’s only when you try to transfer money off PayPal do you notice that these transactions aren’t exactly instant.

For instance, if you transfer money from PayPal to your bank account, it usually takes a few days because that’s an interbank transfer from Paypal’s bank to your bank.

But you can still get around that. If you’ve used PayPal, Venmo, Cash App, Zelle and similar services, you might have seen that, for an extra fee, they allow you to transfer money from those apps to your bank account within minutes.

They do this by utilizing networks operated by either Visa (Visa Direct), Mastercard (Mastercard Send), or the Clearing House (RTP).

Like FedNow, these are other systems that help move money around electronically, but they’re run by private companies.

Building Blocks

So, as you can tell, the payment landscape is quite complex. You have a mix of services provided by private companies, as well as the Federal Reserve.

And these services compete with each other, but they complement each other as well.

For instance, if you send money from Venmo to your bank account, Venmo sends the money to you through the ACH network, which is operated by the Fed.

Or if you use Zelle to send money from your bank account to someone else’s bank account, Zelle transfers the funds using the RTP system (which is an instant payments system owned by a group of big banks) and the RTP system uses joint accounts at the Federal Reserve to ultimately move money from bank to bank.

As you can see, these payment systems and services can be mixed and matched and layered on top of each other.

FedNow is just another system and building block that banks and other companies can use to improve the payment experience for their customers.

Now, I should mention that we won’t be using FedNow directly. It will be available to banks, which will in turn likely offer it to their customers—people like you and me, as well as apps like Venmo, PayPal and Cash App.

So, we’ll use it when we use our banking apps or these other apps (it will power some of the payment capabilities within these apps and most people won’t even be aware they’re using it).

Hopefully, you now have a better understanding of what FedNow is. It isn’t anything nefarious. It’s just a boring piece of payments infrastructure that will help us send and receive payments faster.

A lot of other countries already have similar systems, like the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in India, and Pix in Brazil. And for the most part, they have been well received by consumers and businesses.

The U.S. has been lagging many other countries when it comes to adopting modern and efficient payment systems. FedNow will help the country catch up.