Government Reacts To Bank Failures

The government has been working overtime to protect the economy from the fallout of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse on Friday.

The government has been working overtime to protect the economy from the fallout of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse on Friday. We saw some big developments over the weekend, but people are still kind of nervous.

Here’s what’s going on.

As you might know, SVB was taken over by the government last week after its customers tried to take $42 billion out of the bank in a single day.

It was a massive bank run that overwhelmed the amount of cash that SVB had on hand.

There’s a whole backstory about how Silicon Valley Bank got into this situation, but in a nutshell, it had a very homogenous customer base (mostly tech startups) who were facing hard times and primarily kept uninsured deposits at the bank—or deposits worth more than the $250,000 amount that’s covered by FDIC insurance.

SVB also made some relatively risky investments over the past couple of years.

Specifically, the bonds it purchased— like mortgage-backed securities— don’t get paid back for many years, which meant that their prices went down a lot when interest rates spiked in 2022.

What SVB just went through is what’s known as a liquidity crisis, a situation where it didn’t have enough cash to pay its obligations in the short-term.

But if it had enough time, the bonds that it owned would eventually be paid back in full and then it would have enough money to pay its customers back.

The problem is when your customers demand a huge amount of their money back all at once, you don’t have the luxury of time. You pay your customers back with whatever cash you have on hand and then when you get through all of that, you have to sell your other assets at fire sale prices.

That pushes the prices of those assets down, causing more panic and customer withdrawals, followed by more forced selling of assets in a vicious cycle.

Before you know it, a liquidity crisis turns into a solvency crisis, where the bank can’t pay its customers back no matter how much time it has.

To prevent that situation, the government took over SVB.

It stopped the vicious cycle and it said that everyone with insured deposits would have access to their money on Monday.

But it also said that the uninsured deposits at SVB wouldn’t be paid back until later—no one knew exactly when it would be or how much of the uninsured deposits would be paid back.

It all depended on whether the government could find a buyer for the entire bank or if it couldn’t, how much money it could recoup by selling SVB’s assets piece by piece.

As people digested this news, panic began to grow over the weekend. Not panic about SVB— that bank had already shut down—but panic about other banks that have similar characteristics: banks that have a lot of uninsured deposits, banks that cater to one or a handful of industries, etc.

If you were on Twitter over the weekend, you saw a bunch of people with huge followings predicting massive bank runs all across the country at community and regional banks. And that was concerning because bank runs are a psychological phenomenon.

If people panic based on what they see online or wherever, and that causes a bank run, that can cause a liquidity crisis at a perfectly healthy bank. And then that liquidity crisis could turn into a solvency crisis after the bank sells its assets at fire sale prices.

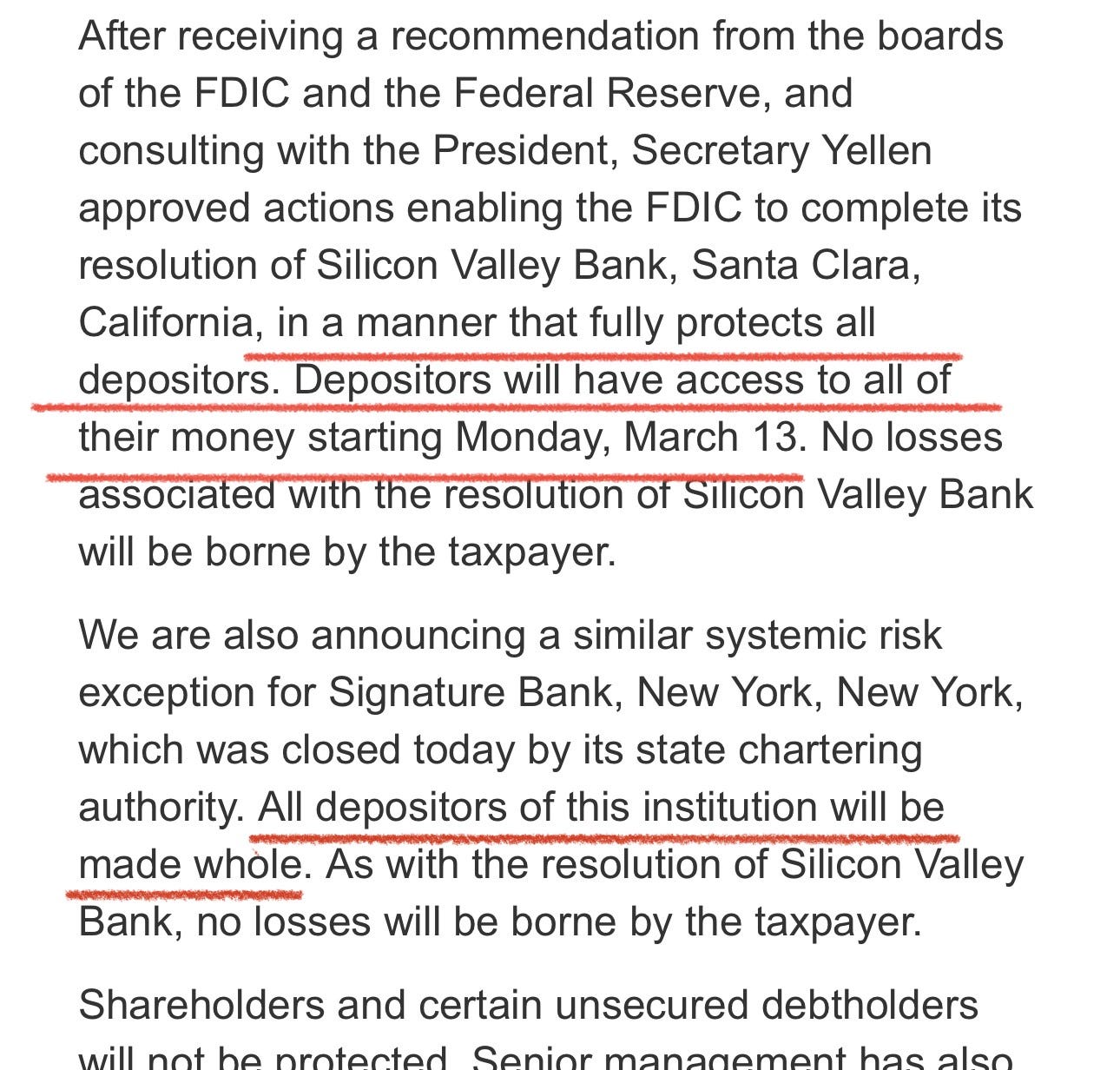

The government wanted to prevent this from happening, so it did a couple of things. The first is it guaranteed all depositors in Silicon Valley Bank.

Whether they had insured deposits below $250,000 or uninsured deposits of more than $250,000, they would have access to their money starting this week.

And it did that same thing for another bank, New York-based Signature Bank, which authorities had shut down over the weekend.

The second thing that happened is the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve, opened a new program (Bank Term Funding Program) through which it would offer loans of up to one year to banks who pledge certain high quality assets as collateral.

In other words, assets like Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities can be used to get loans from the Fed, making it so banks don’t have to sell them at rock bottom prices during times of stress.

And the great thing for banks is that the assets that are pledged as collateral for the loans will be valued at par—meaning their original full price—not the lower market prices that they currently trade at.

If this program was available last week, Silicon Valley Bank could have taken its bonds and gotten a loan from the Fed, which it could have then used to pay its customers.

It wouldn’t have had to sell any assets at fire sale prices and it wouldn’t have run out of cash period.

So these were big moves by the government over the weekend and they headed off what could have been an ugly week for other banks this week.

If the government didn’t act, the concern was that people would see what happened at SVB and they’d pull money out of all of the other small and medium sized banks where their deposits weren’t fully insured, and put them either into the mega banks that are considered “too big to fail,” or into super safe investments like government money market mutual funds.

So with the actions we saw over the weekend, the urgency to do this wasn’t as great. By guaranteeing all deposits at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, the government put an implicit guarantee on uninsured deposits at other banks as well.

Now the thinking is, “Yes the government isn’t explicitly saying that all deposits at all banks are guaranteed, but if they offered a full recovery for depositors at SVB and Signature Bank, they’ll probably do it for other banks as well.”

And then on top of that, you have this new Fed facility that allows banks to borrow money so they can meet really big withdrawal requests from their customers without dumping their assets at a loss.

This all goes a long way towards stemming any potential contagion from the collapse of SVB and protecting the soundness of the banking system.

But even so, it didn’t stop some people from continuing to worry about the health of specific banks. We saw shares of several medium sized regional banks plummet on Monday.

First Republic Bank fell by 60%, Western Alliance Bank dropped 47%, and Zions Bank lost more than a quarter of its value.

The size of these declines was shocking.

But what I think it comes down to is this: investors are worried that even with everything the government did over the weekend, it doesn’t mean that these banks can’t experience bank runs.

Yes, most deposits in the country are safe today based on the example set by SVB and thanks to the Fed’s new lending program, but if people are still worried, you could see runs on certain banks.

Think about it: even after everything that government has done to try to assure you that your money is safe, you could take money out of a smaller bank and put it into larger bank, where it might feel like your money is safer.

And if that happens enough, some of these other banks can theoretically meet a similar fate as SVB.

They won’t run out of cash probably—they can just borrow money from the Fed to meet withdrawal requests— but the amount of customers and deposits they have can shrink significantly, which could have a crippling effect on the banks’ businesses, reducing their profits and stock prices.

That’s the fear that dragged these bank stocks down on Monday. For their part, the banks have responded by saying that they’re fine and they aren’t seeing significant customer withdrawals.

So we’ll see what happens. We now know that in the fast moving, digital, highly-connected world we live in today, a panic-induced bank run can cripple a bank very quickly.

Will that happen to other banks like it happened to SVB and two other banks last week?

It certainly could, but compared to last week, depositors of all sizes have much less reason to panic this week because of all the actions that the government took over the weekend.

Today, it’s less likely, though not impossible, that other banks will fail in the same way that SVB did.