How AI Turned Memory Into A Bottleneck

Is this time different for memory stocks?

An unexpected company has become one of the hottest stocks in the market. With a market cap that recently crossed $400 billion, Micron Technology has climbed roughly fourfold from where it traded a year ago and now sits among the top 20 companies in the S&P 500.

Micron makes memory chips, a product category that for most of its history has been defined by brutal cycles, weak pricing power, and repeated periods of overcapacity. When memory stocks rally the way they have recently, experienced investors usually start nervously eyeing the exit.

Is this time different?

How AI Changed Memory

To understand why Micron suddenly matters so much, it helps to look at how modern AI systems operate.

Over the last few years, technology companies have been racing to build massive data centers to power tools like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. These systems don’t run on conventional computers. They are made up of thousands of chips working together, continuously moving enormous amounts of data.

That data has to live somewhere while the system is operating, and the speed at which it can be accessed increasingly determines how much work the system can do.

Most computers use different types of memory for different jobs. Some memory lives directly on the processor and is extremely fast but limited in size. A larger pool of short-term memory sits nearby, holding data that is actively being used. Beyond that is long-term storage, which is slower but cheaper.

That basic structure still exists today, but AI places an unusually heavy burden on the middle layer in particular. AI models constantly move huge amounts of data in and out of memory. As models grow larger and conversations last longer, the volume of data moving through the system increases dramatically.

HBM Becomes The Bottleneck

This is where high-bandwidth memory enters the picture.

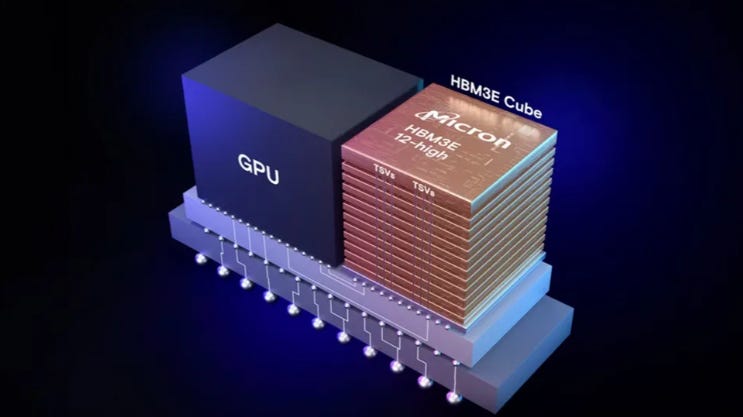

In AI systems, short-term memory increasingly comes from HBM, which is a specialized type of memory that is stacked vertically and placed directly next to the processor. This physical proximity allows data to move between memory and processor far faster than in traditional designs.

In modern AI systems, the processor is most often a GPU supplied by Nvidia, though there are competing GPUs from AMD and custom AI chips from other large technology companies, such as Alphabet’s TPUs.

HBM effectively fuels these processors by keeping them supplied with data quickly enough to operate efficiently. Without HBM, AI chips would be far less effective, regardless of how powerful they are.

The importance of HBM has been a major benefit for the companies that manufacture it. Today, only three companies produce HBM at scale. Micron is one, and South Korea’s SK Hynix and Samsung Electronics are the others.

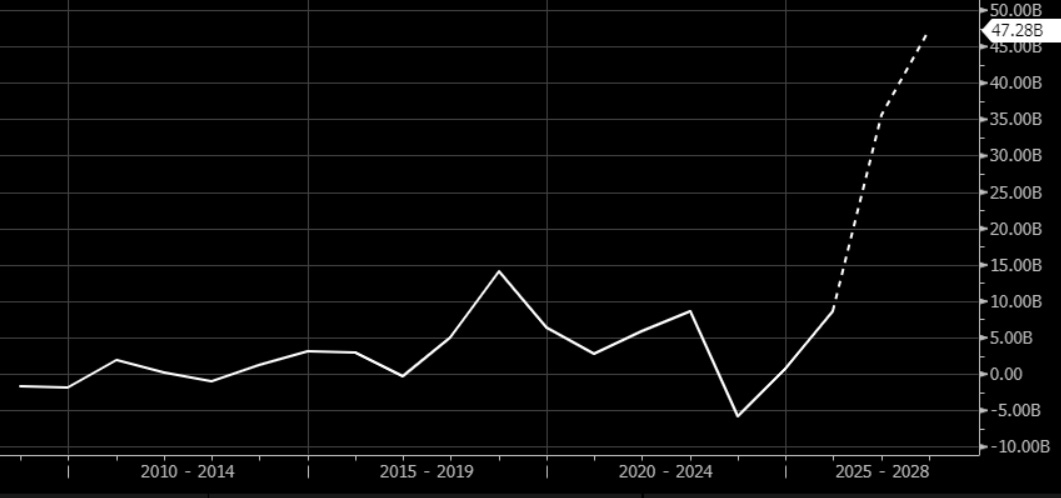

As demand has skyrocketed, prices for HBM have surged. Micron is expected to generate close to $50 billion in profit next year, up from less than $10 billion last year.

Those fat profits are motivating Micron and its competitors to expand capacity, but doing so is not trivial. HBM is more expensive to produce, more complicated to manufacture, and more tightly integrated with the AI chips it serves than traditional memory.

The enormous demand for HBM is having spillover effects as well. As more memory production is diverted toward HBM, less capacity is available for the memory used in smartphones and PCs.

According to IDC, this shift is already putting upward pressure on memory prices for consumer devices, forcing phone and PC makers to either raise prices, cut specifications, or accept lower margins as supply tightens.

This represents a meaningful change in the memory market’s center of gravity. For decades, consumer electronics were the primary driver of memory demand. Today, AI data centers are increasingly setting the terms, and they are far less sensitive to price than consumers buying phones or PCs.

Cyclical or Structural?

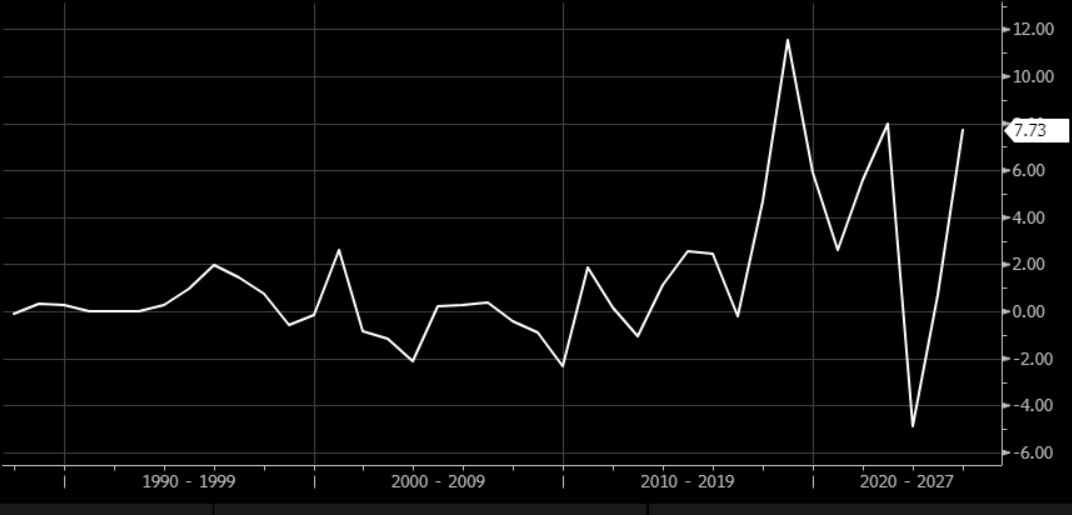

None of this eliminates the risks associated with memory stocks. The industry has historically been cyclical. Prices rise, companies build capacity, supply eventually catches up, and prices collapse. That cycle has burned investors repeatedly.

The open question is whether AI has altered the structure of the market enough to change how that cycle plays out.

Some investors argue that high-bandwidth memory is no longer a true commodity. It is more complex and performance-critical, which could make pricing more resilient than in past memory cycles.

Others remain skeptical and argue that memory is still memory, and that given enough time, capacity expansion and competition will erode pricing power just as they always have.

Micron’s stock reflects both sides of this debate. At a roughly $400 billion valuation, the company is trading at about 8.5 times projected 2027 earnings. That valuation may appear low on the surface, but it reflects the historical cyclicality of the memory business.

The chart below shows how volatile Micron’s earnings have been over time. As recently as 2023, the company lost $4.89 per share.

Despite the debate, most observers agree that the current memory bottleneck is likely to persist at least through the end of this year. Beyond that, visibility becomes far less clear.

Nvidia’s Big Bet

One development worth watching involves recent moves by Nvidia. In December, the company struck a $20 billion licensing deal with a startup called Groq, which makes LPUs, or language processing units.

LPUs are AI chips designed to run AI models extremely fast and consistently. What’s interesting is that they don’t rely on HBM in the same way GPUs do. Instead, they use a different design, with more memory embedded directly on the chip.

LPUs are great for running certain AI tasks efficiently, but they’re not a replacement for the general-purpose systems that pair GPUs with HBM.

But the deal does send an important signal. It suggests that Nvidia is exploring alternative chip designs, either because they’re better for specific tasks, or because they reduce reliance on scarce, expensive high-bandwidth memory.

The Bigger AI Trade

Zooming out, the surge in memory stocks like Micron fits a pattern we’ve seen throughout this AI boom. New bottlenecks keep emerging in the AI supply chain.

First it was GPUs. Then it was power. Then cooling. Now it’s memory.

Each time a new bottleneck appears, stocks tied to that part of the supply chain surge. Right now, demand is strong enough that nearly every part of the AI supply chain has pricing power.

But over the long run, only the companies with real, durable competitive advantages will be able to sustain it.

The challenge for investors is figuring out which parts of the AI supply chain have those advantages, and which are simply benefiting from a temporary bottleneck.