How Silicon Valley Bank Failed

How can a bank be worth $16 billion one day and then be worth close to zero two days later?

How can a bank be worth $16 billion one day and then be worth close to zero two days later?

As you might have guessed, I’m talking about Silicon Valley Bank—a bank that was one of the largest in the nation a few days ago, but depending on what happens in the coming weeks, might not exist in the future.

The easiest way to make sense of what happened to SVB is to think of its demise as a being caused by four separate, but connected acts— almost like some kind of Greek tragedy.

Act 1: The Tech Bubble

The first act was the tech bubble.

This took place in 2020 and 2021. Obviously, the world was very different back then. We were in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Fed had just cut interest rates to zero in order to support the economy.

The federal government sent out thousands of dollars worth of stimulus checks and a lot of people were stuck at home where they used new technologies to help them work and to entertain themselves.

It turns out that this was the perfect environment for a bubble to form.

With interest rates at zero and demand for tech products and services going through the roof, investors sent stocks of technology companies into the stratosphere.

That enthusiasm filtered down into the market for earlier stage tech companies as well.

These tech startups were funded by venture capital firms, who were suddenly willing to invest millions or billions of dollars into any tech startup that could come up with a promising story. Flying taxis, space tourism, quantum computing—you name it—it all got funded during the easy money era of 2020 and 2021.

So you had all these starts up raising a ton of money during those years and where did they put that money?

They put it in Silicon Valley Bank—the preeminent bank for tech startups.

SVB had deep connections with the tech startup ecosystem. It went above and beyond to cater to young up-and-coming tech companies, doing whatever was necessary to get them to bank with SVB.

The bank reportedly did business with half of all VC-backed companies in the U.S.

Between 2020 and 2021, as the tech bubble inflated, SVB’s deposits more than tripled from $62 billion to $189 billion as its tech startup clientele became flush with cash.

Act 2: SVB’s (bad) Investments

With tens of billions of dollars coming into the bank on such short notice, Silicon Valley Bank had to quickly decide what it wanted to do with all of this new money.

More deposits meant that SVB had the capacity to make more investments of its own. But what kind of investments it made was up to the bank.

It could have tried to make loans to its customers. But the startups that SVB catered to already had a lot of cash from their VC investors; they didn’t really need bank loans.

SVB could have also bought really safe government securities like Treasury bills. The great thing about T-bills is they are issued by the U.S. government and don’t fluctuate much in price. They get paid back in less than a year, and so they are essentially the safest investments in the world.

The problem is, with interest rates at zero, you couldn’t really make much money on T-bills. They were paying almost nothing.

So in order to generate a little bit more interest—between 1% and 2%—what SVB did was buy bonds that took much longer to get paid back, like long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

This enabled the bank to generate higher returns, but with higher risk, since long-term bonds are really interest rate sensitive. Their prices go up a lot if interest rates go down, but their prices go down a lot if interest rates go up.

Making these investments would prove to be a crucial mistake for SVB.

Act 3: The Bursting of the Tech Bubble

In 2022, the good times ended.

Whether it be because the Fed started hiking interest rates aggressively to combat inflation or people started to realize that they were being irrational, in 2022, the demand for tech investments plunged.

First tech stocks within the public stock market crashed and then that filtered into the private market, where tech startups operate.

All of a sudden, venture capitalists weren’t willing to mindlessly plow money into these startups, most of which didn’t make any profits.

Less money for startups meant that they had less money to put into SVB. And what money they had in the bank, they started to pull out to pay their workers and for other expenses.

After peaking at $198 billion in March 2022, SVB’s total deposits dropped to $165 billion in February 2023.

So this went on throughout 2022 and into early 2023. It wasn’t good for the bank but no one thought the problems facing SVB were that severe.

But then last week, the ratings agency Moody’s called up SVB and told them that it was about to downgrade the bank’s credit rating.

Moody’s saw that the value of the investments that SVB made over the last couple of years had dropped significantly, and that they weren’t generating much income for the bank since they were bought when interest rates were much lower.

At the same time, Moody’s noticed that SVB was having to pay higher and higher interest rates to its customers on their deposits. This was squeezing the bank’s margins.

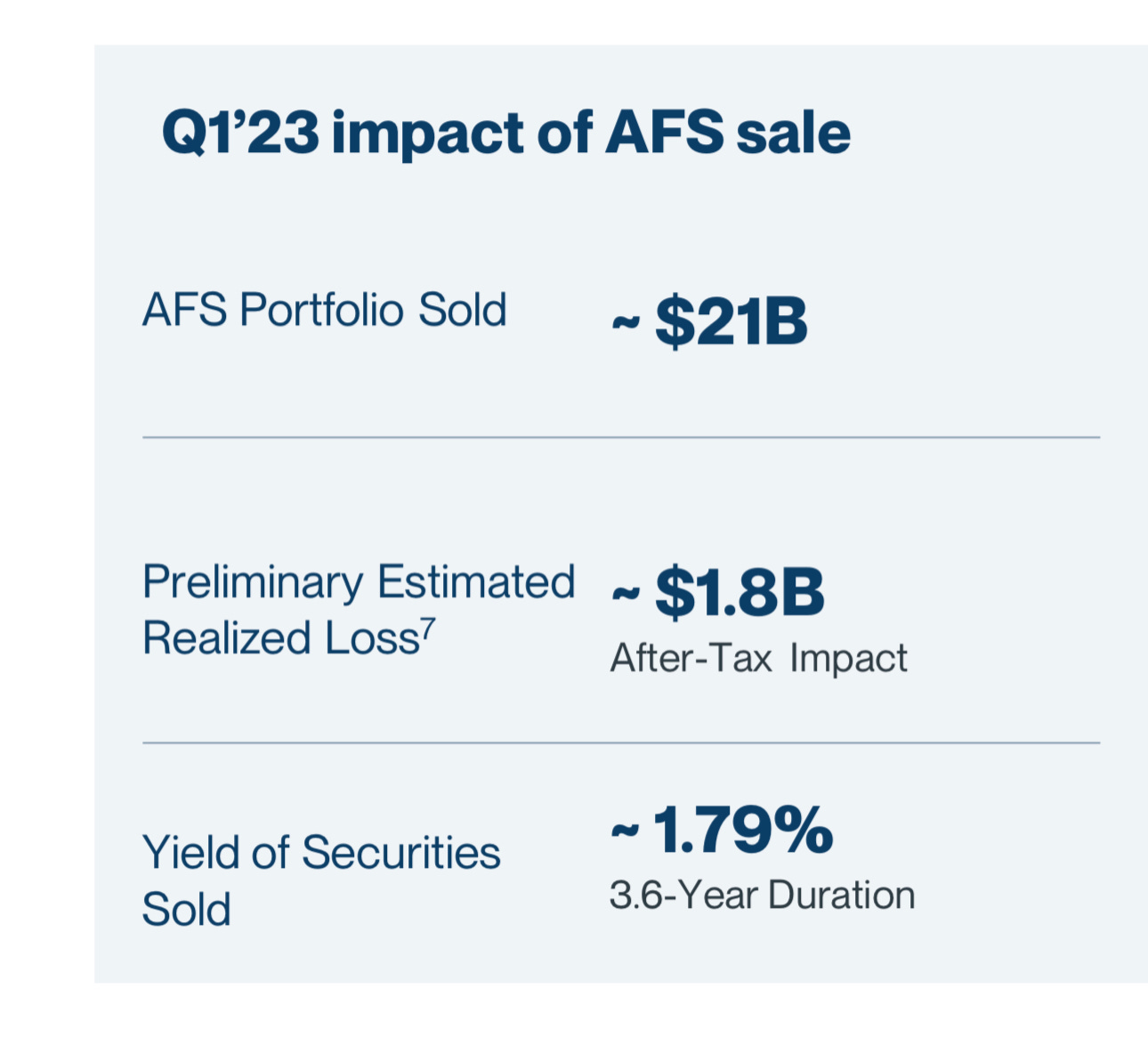

The threat of the credit downgrade from Moody’s caused SVB to scramble. The bank came up with a plan to sell $21 billion worth of its long-term assets, which it would then reinvest into shorter-term assets that were less volatile and had higher interest rates.

The bank sold the assets earlier this week and it lost $1.8 billion on the sales.

Then this Wednesday, the bank came out and announced that it would sell $2.25 billion worth of stock to investors in order to make up for those losses.

But instead of reassuring investors, the plan caused panic.

Act 4: The Bank Run

For most people, the news of SVB selling assets at fire sale prices and then trying to raise money through a stock offering came completely out of left field.

People thought they had their money in a safe, reputable bank. Once they learned that that might not be the case, everyone started to pull their money out.

Venture capital firms advised the startups that they invested in to transfer their funds out of the bank ASAP. The Silicon Valley tech community, which is all kind of tuned into the same news and follows the same people on Twitter, acted all at once.

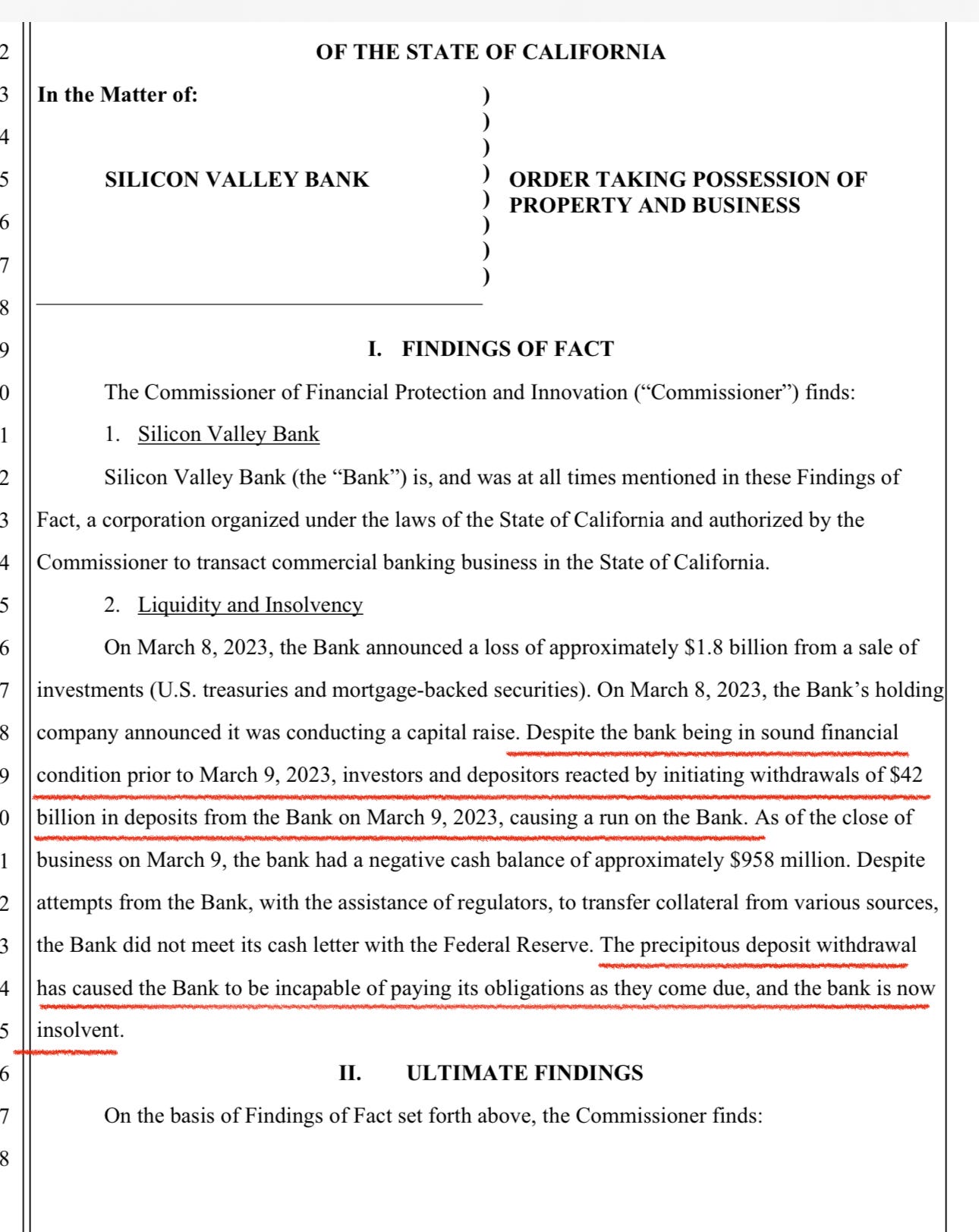

On Thursday, depositors at the bank collectively initiated withdrawals of a whopping $42 billion. That completely overwhelmed the amount of cash that SVB had on hand, making the bank insolvent.

As a result, California authorities took over the bank and handed it off to the FDIC. Silicon Valley Bank had failed.

The Story Continues

That’s Act 4 and you could say the story is over, but there might be some more developments in the coming days and weeks.

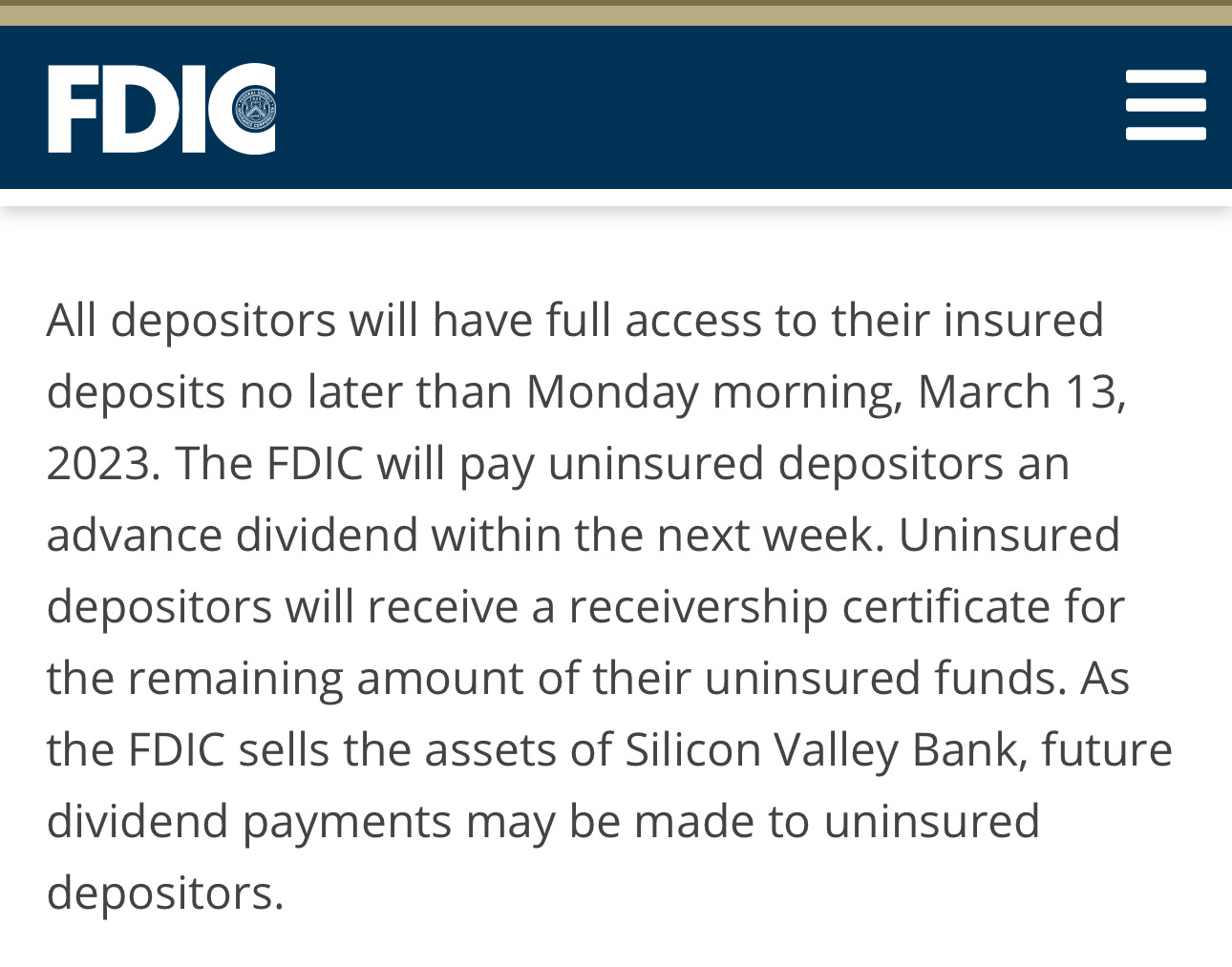

Starting on Monday, anyone who had deposits at SVB that are covered by FDIC insurance—or deposits of $250,000 or less—will have access to that money. But anyone with uninsured deposits—meaning deposits at the bank beyond $250K—will have to wait to find out how much money they’ll be getting back.

This is kind of a scary thing because more than 85% of the bank’s deposits were uninsured.

Remember, the customer base of SVB was mostly made up of tech startups and they had tens of millions, or hundreds of millions of dollars at the bank in many cases.

Now they don’t know how much money they’ll get back and whether they can even pay their workers next week.

There’s two pieces of good news though. One is that the FDIC is trying to find a buyer for SVB that can take over the bank in its entirety and resume its operations relatively seamlessly. If that happens, depositors will most likely be made whole.

But even if that doesn’t happen—maybe because the value of the bank’s assets is now less than its liabilities—or for whatever reason, then the FDIC will sell SVB’s assets piece by piece.

Even in that scenario, uninsured deposits will most likely get their money back because the government wants to reassure the public that their money is safe at their local bank. They don’t want to see contagion where bank after bank fails because people are nervous about their money.

In most cases where banks have failed in recent years, uninsured deposits have been fully compensated. So that’s good news.

But still, it’s kind of scary that the 16th largest bank in the U.S. went under and most of its deposits aren’t completely guaranteed to be paid back in full. They probably will be, but it’s not guaranteed.

That’s why some people, like hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, are now worried that we might see similar runs at other banks which have a lot of uninsured deposits.

Now, don’t get me wrong. That is possible and financial panics tend to feed on themselves and spread. You never want to rule anything out.

But SVB was unique in the sense that it catered to a single, very volatile industry. When that industry went bust, it caused a lot of strain on the bank’s customer base. Most banks—especially the top 10 U.S. banks which hold more than half of all deposits—are much more diversified across industries and across the types of depositors they have—from regular people, to small businesses to large businesses, etc.

So those big banks, which are also considered to be “too big to fail” by regulators, are probably safe.

Where we might see strains are in other banks like SVB, which focus on a homogenous set of customers that are going through tough times.

The downfall of SVB and the crypto-focused bank Silvergate earlier this week probably aren’t the start of a 2008-style banking crisis. But we have to stay vigilant, and the government has to do all it can to reassure the public that these are isolated events.