How The 2023 Debt Ceiling Battle Will Unfold

If you thought the process that got Kevin McCarthy elected as Speaker of the House was chaotic, wait till you hear about what could happen in the coming months.

(You’ll find the text version of “How The 2023 Debt Ceiling Battle Will Unfold” below this embedded video)

If you thought the process that got Kevin McCarthy elected as Speaker of the House was chaotic, wait till you hear about what could happen in the coming months.

In order to get elected Speaker after 14 failed attempts, McCarthy had to make deep concessions to more than dozen lawmakers from the far-right flank of his party.

We now know what some of those concessions were.

The most significant one was a promise to create a plan that balances the federal budget over the next 10 years. To balance the budget in that timeframe would likely entail cutting hundreds of billions of dollars of spending on everything from Social Security and Medicare to the military to education.

McCarthy also promised the hardliners that unless their demands to reduce and cap government spending were met, Congress wouldn’t lift the debt ceiling—something that could be catastrophic for the U.S. economy.

The problem with these plans that McCarthy made with the ultraconservatives in his party is that they’re not going to fly with Democrats. But not only that—some Republicans in the Senate and even some Republicans in the House would be very reluctant or even hostile to attempts to cut defense spending and politically-sensitive programs like Social Security and Medicare.

But McCarthy made these concessions to the hardliners in exchange for their support and they expect him to follow through. If he doesn’t, well, it just so happens that another concession he made to them makes it much easier to remove him as Speaker.

In addition to the budget-related commitments he made, McCarthy agreed to a rule change that makes it so any one member of Congress can call for a vote to remove the Speaker.

So if McCarthy goes against the hardliners’ wishes, they could try and remove him from his position.

Echoes of 2011

A lot of what’s happening today is similar to 2011, when a group of Republicans called the Tea Party Caucus refused to lift the debt ceiling unless then-President Obama agreed to significant spending cuts.

Obama and the Republican-controlled House agreed to a last-minute deal, but not before pushing the U.S. to the brink of default, something that prompted credit ratings agency Standard and Poor’s to cut the United States’ credit rating for the first time in history.

Another debt ceiling standoff occurred in 2013 when Republicans attempted to extract concessions from Democrats, but this time the Democrats didn’t give in, and after weeks of brinksmanship, a small minority of House republicans came together with Democrats to lift the debt ceiling.

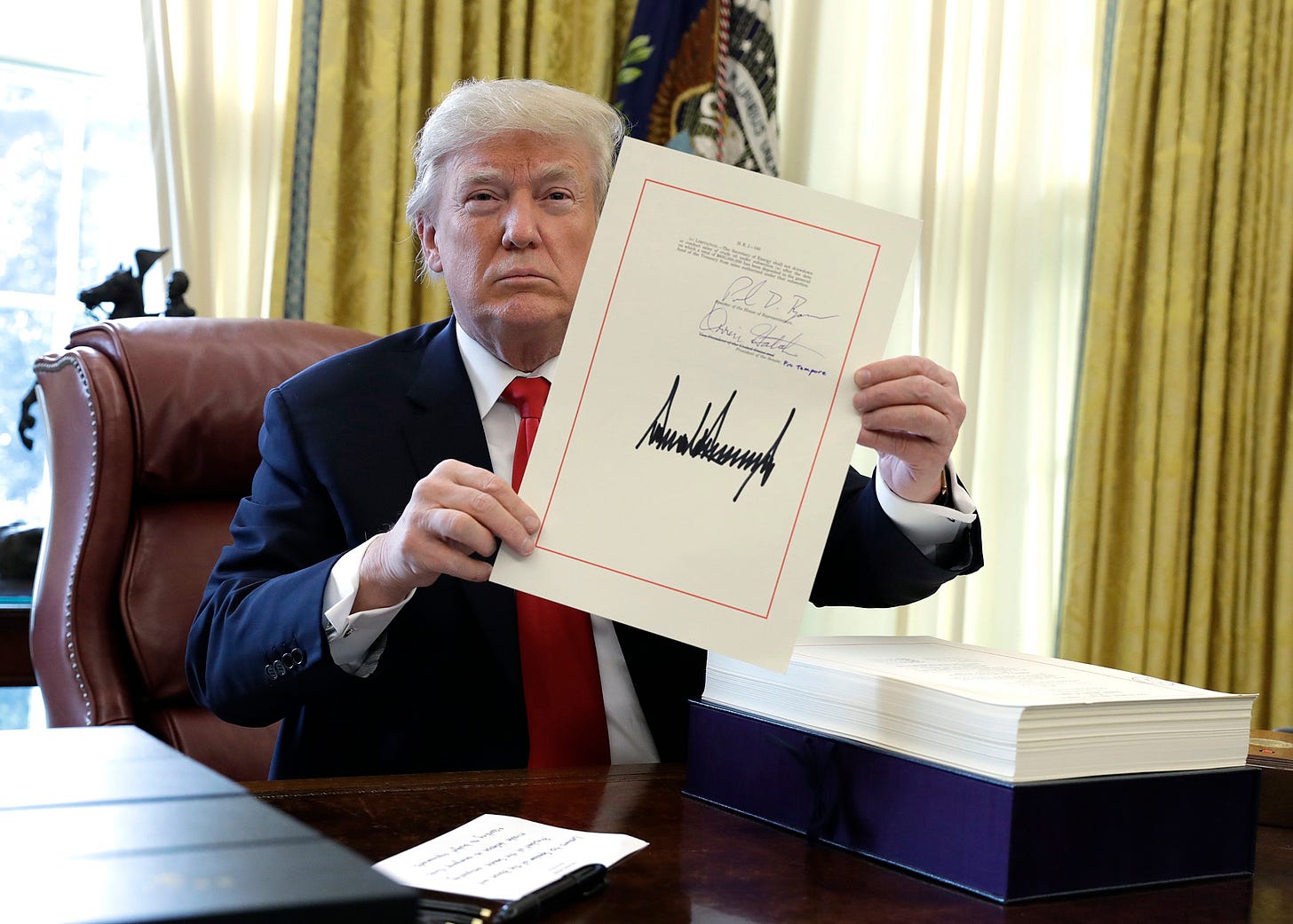

And in case you’re wondering, during the Trump presidency, a period in which Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress for two years, there were no problems raising the debt ceiling when the government needed to borrow money to fund the $1.5 trillion Trump tax cats.

In other words, the battle over the debt ceiling isn’t just an ideological standoff, it’s a matter of politics as well.

Republicans have an incentive to extract as many concessions from President Biden and the Democrats as they can ahead of next year’s election.

This is what we’re likely to see: in the lead up to date when the federal government runs out of borrowing capacity—which is expected to be sometime during the second half of this year—we’re going to see Republicans dig in and try to get Democrats to agree to their demands.

At the same time, Democrats will probably try give as little ground as possible—knowing that when they compromised in 2011, it led to big spending cuts, but when they held firm in 2013, they were able to secure a clean debt ceiling increase without making any significant concessions.

How this all plays out will depend on how close to the edge McCarthy and his hardliners are willing to take the economy—and whether they’re willing to actually go over that edge.

There’s a couple of ways this could go.

Scenario #1:

McCarthy could break his promise to the hardliners and bring a bill to increase the debt ceiling to the floor. That could be a clean debt ceiling increase with no string attached—which is unlikely—or it could be one that includes some spending cuts that are small enough for Democrats to swallow but large enough for moderate Republicans to go along with as well.

But those types of bills without dramatic spending cuts could lead to backlash from the hardliners, who could force a vote to oust McCarthy.

Remember, it now only takes one member to force “a motion to vacate the chair,” a procedure that can be used to try to remove the Speaker of the House from office.

But in order to remove McCarthy, the hardliners would need to be joined by Democrats to do so—which seems unlikely.

So McCarthy could break the promises he made to his right flank without necessarily getting removed from his position as Speaker, but that would also create another round of in-fighting within his own party, and make him reliant on Democrats to get a bill passed and keep his position as Speaker.

Scenario #2:

Another scenario is McCarthy could stick to the demands of his right flank and be willing to allow the U.S. government to default on its debt if Democrats don’t agree to deep spending cuts.

This would be a really bad situation for the economy and would effectively put the far right of the Republican party in the drivers seat when it comes to budget negotiations.

But even if this scenario plays out, there are ways to avoid a catastrophic default on the U.S. debt.

There’s something called a discharge petition, which is a tool that allows a bill to be brought to the House floor for a vote if a majority of members want it. This is a way for a bill to bypass the Speaker, but it would require some Republicans to cross party lines and join with Democrats to get the 218 signatures needed on the petition.

Then once, the bill is on the floor, Democrats and a small number of Republicans would need to join together to get it passed.

As you can see, there are ways out of this mess but it’s a very uncertain environment. In my mind, the big questions are:

-How many concessions on spending cuts will Democrats be willing to make—if any?

-Will some Republicans—including McCarthy himself— be willing to reject the uncompromising demands of ultraconservatives and make compromises with Democrats?

-And ultimately, will the U.S. default on its debt?

The worst-case scenario, where the U.S. actually defaults because a compromise can’t be reached is possible. But it would be extremely unfortunate.

Because remember, the U.S. government is only borrowing money to pay for spending that Congress already authorized.

The debt ceiling was created by Congress in 1917 to give the Treasury Department more flexibility in how it financed government spending.

Prior to that, Congress would authorize an expenditure and then have to pass a separate bill that instructed the Treasury how to finance that expenditure, whether it be with long-term Treasury bonds, short-term Treasury bills, taxes, etc.

As government spending grew in World War I, this became cumbersome, so Congress delegated that responsibility to the Treasury. It said: “we’ll tell you what to spend money on; you figure out how you want to pay for it.”

A Dangerous Road

To me, it’s a little bit odd that one part of the government—Congress— would prevent another part of the government—the Treasury department— from paying for things that the first part of government told it to spend money on.

And not only is it odd, it’s dangerous.

A default would lead to a deep recession in the U.S. and worse, it could have long-lasting negative consequences for the creditworthiness of the U.S. government, and by extension the U.S economy.

Fortunately, even if we get to position where Republicans and Democrats can’t reach a deal to raise the debt ceiling, there are some really unconventional, untested things that the president can do to try and avoid a default.

Those include prioritizing payments to Treasury bond holders over everyone else; invoking the 14th amendment of the constitution—which says that “the validity of the debt of the United States shall not be questioned;” and minting a $1 trillion platinum coin.

These workarounds might be successful, they might not. It’s good that they’re potentially available, but let’s hope we don’t get to the point where they need to be tested.