India's Richest Man vs Hindenburg Research

A tiny New York-based research firm caused India’s richest man to lose almost $40 billion in a week.

A tiny New York-based research firm caused India’s richest man to lose almost $40 billion in a week. Here’s what happened.

The story involves Hindenburg Research, a 10-person firm headed by Nate Anderson.

What Hindenburg does is try to identify companies doing shady things. It then releases evidence of those shady things and if it’s right, it profits from the demise of those companies.

About a week ago, on Jan. 24, Hindenburg released an extensive report accusing the Adani Group of “the largest con in corporate history.”

It said that it had uncovered “brazen accounting fraud, stock manipulation and money laundering at Adani” that took place over the course of decades.

That type of accusation is a big deal for any company, but Adani Group isn’t just any company—it’s India’s second-largest conglomerate—and it’s headed by Gautam Adani, an insanely rich businessman who is reportedly close with India’s prime minister Narendra Modi.

A week ago, Gautam was the world’s fourth-richest man with a net worth of $120 billion. Today, he’s worth $84 billion, putting him at No. 10.

Gautam’s net worth has been tumbling along with the price of his stocks.

The conglomerate known as the Adani Group is made up of many different companies, nine of which are publicly traded.

These are industrial companies focused on the development and operation of things like ports, mines, airports, data centers, and power plants.

Over the past few years, the stocks of these companies have exploded to the upside, pushing the value of the Adani Group to more than $200 billion at its peak.

But Hindenburg Research says that most of that value is hot air.

Hindenburg’s report painstakingly details how the Adani Group uses a sprawling, convoluted web of offshore shell companies to evade regulations, manipulate its stock prices, and inflate its profits.

Here’s how it does it.

Indian securities regulations restrict insiders from owning more than 75% of a publicly traded company’s stock. These rules are meant to prevent stock manipulation.

The assumption is that if there’s not a lot of stock held by non-insiders, then it’s easy for insiders to manipulate the stock, pushing it up and giving the appearance of strength.

Four of Adani’s stocks have insider ownership that’s brushing up against the 75% insider ownership limit, but Hindenburg says that if you include stocks held by suspicious offshore shell companies, the actual percentages are much higher.

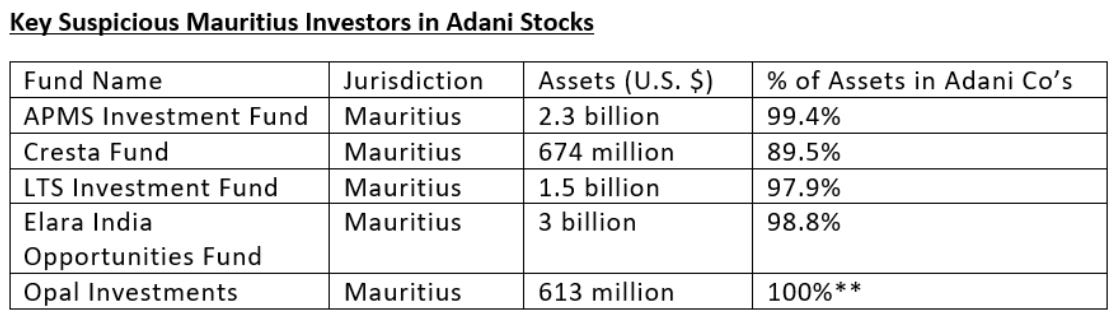

Hindenburg looked at five of these offshore entities that are set up as investment funds and they came up with some pretty suspicious findings.

All five of these funds are controlled by the same holding company, there’s very little information about them anywhere, and their assets mostly consist of Adani stock.

Adding to the suspicion, Hindenburg says that it found data which showed that these funds have been coordinating their trades in Adani stocks, artificially inflating the volume and price of the stocks.

Essentially, Hindenburg believes that these funds are being used by Gautam Adani and other insiders to get around the 75% rule and manipulate his companies’ stocks.

But that’s not all.

The Hindenburg report details transactions between the Adani Group and dozens of other offshore entities, many of which are connected to Gautam’s brother Vinod Adani.

Hindenburg says that these shell companies are used to move money in and out of the Adani Group’s publicly traded companies to inflate their reported profits and make the companies look healthier than they are.

The report highlights some really suspicious behavior, like how many of these companies have nearly identical text on their websites and how their websites were created on the same exact day.

In one example, Hindenburg talks about a shell company which lent an Adani company $202 million (NR 15 billion).

According to corporate filings, this company is supposed to be a silver bar merchant, yet there’s little evidence the company even exists.

When Hindenburg sent an investigator to visit the address listed in the corporate filings, they found an “out of office” sign located in a rundown building.

The contact information on the sign was for a man who Hindenburg later found out works at Adani.

The Hindenburg report is filled with countless other examples like these that call into question the Adani Group’s business dealings and financials.

Ordinarily, investors don’t have to worry about these things because external auditing firms look at a company’s financials to make sure they’re accurate and transparent.

But Hindenburg points out that in the case of Adani Enterprises (the largest of the Adani Group companies) the auditor is a tiny company with a staff of less than a dozen people who work out of a small office—hardly the type of auditor that inspires confidence and that you’d expect a giant industrial company to use.

The Hindenburg report also mentions that even if the Adani Group isn’t doing anything wrong, just based on pure fundamentals, the conglomerate’s stocks are wildly overvalued.

As you might expect, the Adani Group wasn’t happy about this report and they responded by slamming Hindenburg, calling the research firm “the Madoffs of Manhattan” while threatening legal action.

Adani claims that the Hindenburg report contains selective misinformation intended to create uncertainty so Hindenburg can profit from its decline.

Adani also said that the Hindenburg report was “a calculated attack on India, the independence, integrity and quality of Indian institutions, and the growth story and ambition of India.”

Interestingly enough, I think that Adani is partly correct, but not for the reasons it thinks.

If Hindenburg is right about Adani, then it does raise questions about the financials of other Indian companies—just like accounting scandals at U.S. companies like Enron and WorldCom two decades ago raised questions about U.S. accounting standards.

Investors want to know that the companies they invest in portray themselves in an accurate manner.

Obviously, Hindenburg has something to gain if Adani were to fall, but that doesn’t mean their analysis is wrong or that they want to see India itself fail.

In fact, Hindenburg’s reputation depends on its research being accurate.

Their most high profile report up until now was a 2020 report accusing Trevor Milton, the founder of electric vehicle company Nikola, of fraud. Two years later, Milton was found was found guilty of fraud and the company’s stock has collapsed more than 90% since the date the report came out.

Of course, that doesn’t mean Hindenburg will always be right.

The verdict when it comes to the Adani Group specifically will come down to whether the allegations Hindenburg made in its report are true.

That remains to be seen, but I think the report raises enough questions to warrant deeper examination of the conglomerate by Indian regulators.

And ultimately, that type of scrutiny will be good for the Indian capital markets and the Indian economy.