Investing In Gold & Platinum

Should you be buying either of these metals as an investment?

In the mid-1800s, aluminum was a sign of wealth. Rich women wore jewelry made of aluminum and the emperor of France provided his most important dinner guests cutlery made of aluminum.

At the time, aluminum was extremely expensive; it was worth more than gold.

Obviously, that isn’t the case any longer, but let me ask you this: which do you think is more valuable today, a bar of gold or a bar of platinum?

If you asked me this question 20 years ago when I was in high school, I wouldn’t have hesitated. I mean, look at all the rappers from back then with their platinum chains and platinum watches.

If they were wearing platinum jewelry, it had to be expensive—and it was.

Platinum was worth a lot, and it was significantly more expensive than gold was two decades ago—$750 per troy ounce versus $380 for gold—or nearly double the price.

But today? That ratio has flipped. Gold is more than twice as valuable as platinum—$1,900 versus $900.

That raises a couple of questions: why is gold so much more valuable than platinum today when it was the other way around for most of the past 100 years? And, should you be buying either of these metals as an investment?

To answer those questions, we need to understand what makes gold and platinum different, but also what makes them similar.

Precious Metals

As you probably know, both gold and platinum are precious metals. A metal is considered precious if it’s valuable—and that can change over time.

You might have gathered from the anecdote at the beginning of this video that aluminum was once considered a precious metal.

It was expensive even though it’s the most abundant metal in the Earth’s crust because aluminum bonds very easily with other elements, and up until the late 1800s, people didn’t know how to cheaply and easily separate it from those other elements.

Once they figured out how to do that using a technique called electrolysis, the price of aluminum plunged (it’s now considered a “base metal”).

Obviously, gold and platinum are different. They are much scarcer than aluminum is, so they’ve always been hard for people to get their hands on.

But that alone isn’t what makes them valuable. For example, another metal, Ruthenium, is three times rarer than gold based on the amount that is in the Earth’s crust, but it’s a fourth of the price ($465/troy ounce currently).

What makes a metal valuable or not isn’t just the amount of it that exists on Earth; it’s how much people want to buy it, combined with how much is available for sale.

Supply

Today, the majority of gold and platinum that is available for sale comes from mining operations. Most of the platinum that is mined in the world—or a whopping 70% of it— comes from South Africa.

On the other hand, gold mine production is distributed much more evenly across the world. China, Russia, and Australia account for around 9% to 10% of global gold production, while Canada, the U.S., Ghana, Peru, Indonesia, and Mexico account for 3% to 5% of world production.

Mine production is where most of the gold and platinum that’s available for sale comes from, but it’s not the only source of gold and platinum supply.

You see, all of the gold and platinum that has ever been mined is still around in some form of another. It’s estimated that around 200,000 metric tons of gold and 10,000 metric tons of platinum have been mined throughout history.

(To put that in perspective, all of that gold could fit into a cube that’s roughly 20 meters on each side, while all of that platinum could fit into a cube that’s 7 meters on each side).

Most of that above ground stock of gold and platinum isn’t available for sale because people are using it. But every year, a little bit of that existing stock is resold onto the market (it’s known as recycled metal).

When you combine mine production with recycled metal, you get the total supply of gold and platinum that is available for sale— which is one half of the equation that determines how valuable these metals are.

The other half is, of course, demand.

Demand

Demand for gold and platinum can be broken down into three broad buckets: jewelry demand, industrial demand, and investment demand.

Both gold and platinum are widely used for jewelry. About half of global gold demand comes from jewelry, while a quarter of global platinum demand comes from jewelry.

Both of the metals are also used in industry. Gold is used in electronics, while platinum is used in the chemical, glass, medical, and automotive industries.

That said, while both have industrial uses, platinum is much more of an industrial metal than gold is. Only 8% of gold demand comes from industry, which compares to 72% of demand for platinum.

In fact, more than a third of platinum demand comes specifically from the automotive industry, where the metal is used in catalytic converters to reduce the emission of harmful gases from vehicles.

I’ll get more into that in a minute, but before I do, let’s talk about the third category of demand: investments.

Gold and platinum are used by people to store their wealth and to protect against inflation. This investment can come in the form of physical bars and coins, or it can come in the form of ETFs—which trade like stocks and hold physical gold and platinum on behalf of investors.

(Some people also make investments in gold and platinum by buying jewelry, so there’s a bit of overlap between jewelry demand and investment demand).

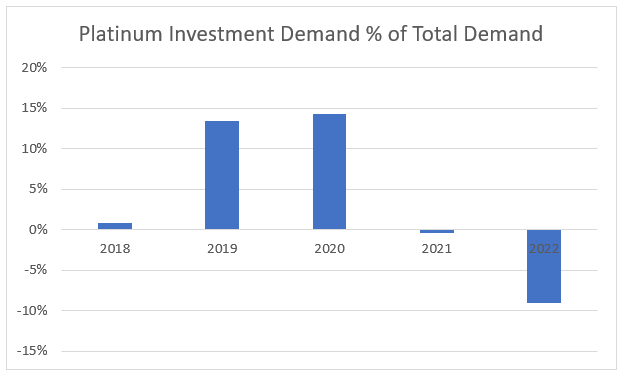

Now, while platinum is considered an investment by some, the demand for platinum as an investment isn’t consistent. For example, in 2020, investments in platinum bars, coins and ETFs accounted for 14% of total platinum demand, while in 2022, platinum investment demand was negative (meaning that investors were net sellers of platinum).

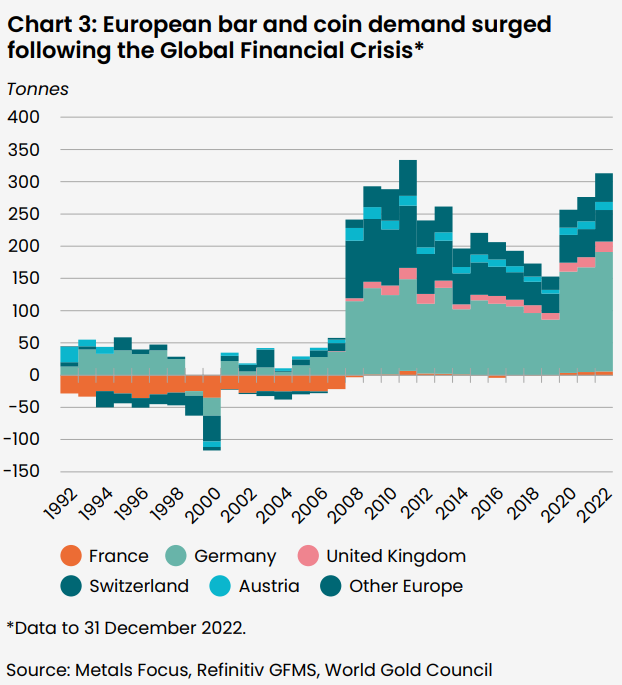

That contrasts with gold, which has a very large and consistent source of demand from investors. Gold investment—which primarily comes in the form of gold bar and coin purchases, but also includes the purchase of gold ETFs—is typically around 25% to 30% of total gold demand (though it can be as high as 50% in some years).

It’s not just individuals who store their wealth in gold. Central banks around the world also buy the metal as a part of their foreign exchange reserves. In recent years, central banks in China, India, Turkey, and many other countries have been stocking up on gold.

These purchases by central banks have accounted for an average of 14% of total gold demand over the past five years.

Gold’s Resurgence

So, now that you’re familiar with the supply and demand drivers of gold and platinum, let’s talk about why gold has performed so much better than platinum over the past couple of decades.

There are really three main reasons why gold has performed so well. One is that central banks of developed countries stopped selling gold.

For about 100 years, most countries in the world operated under the “gold standard,” where paper currencies were convertible into physical gold. To keep this system running, central banks accumulated reserves of gold.

The gold standard eventually morphed into the Bretton Woods system, in which U.S. dollars were convertible into gold, while other currencies were convertible into dollars.

But in the 1970s, that system collapsed and gave way to the current paradigm of fiat currencies, which aren’t convertible into gold or any other asset.

With no need for gold, central banks started selling off their reserves of the metal. Those sales lasted for years, but they finally came to an end around a decade ago, which is about the time that central banks in developing countries began to aggressively purchase gold to diversify their foreign exchange reserves, pushing up demand for the metal.

So, that’s reason No. 1 why gold has performed so well: central banks went from being net sellers to net buyers of gold.

The second reason gold has performed so well is the rise of the Chinese and Indian economies. As Chinese and Indian consumers have gotten richer, their demand for gold—a metal that carries great cultural significance in those countries— has risen in lockstep.

Demand from China and India represented around a quarter of global gold demand two decades ago; today it represents 50% of gold demand.

Finally, the third reason that gold has outperformed over the past two decades is because it’s become increasingly recognized as a store of value and as an investable asset (this ties into the growth of demand in China and India).

Gold has a long history of being considered a safe asset that tends to hold its value over time, but there was a period of about thirty years after Bretton Woods collapsed during which people kind of forgot about it.

Over the past couple of decades, people have started to embrace gold again.

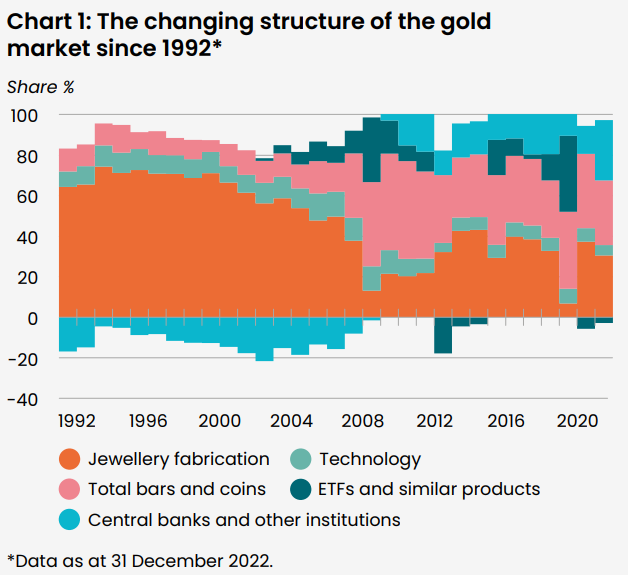

If you look at this chart, you can see the dramatic transformation of gold demand over the past 20 years. Whereas jewelry demand made up the bulk of gold demand in the late 90s and early 2000s, today, there’s much more demand coming from investors, as well as central banks.

So, that’s why gold has done well. Now let’s talk about why platinum has done poorly.

Out of Fashion

Remember that unlike gold, platinum is primarily an industrial metal, with 35% of demand coming from the automotive sector alone.

And what we see is that trends in the automotive sector haven’t been favorable for platinum.

As I said earlier, platinum is used in catalytic converters to reduce vehicle emissions. Starting in the 1970s, the U.S. and other countries started requiring automakers to put these devices in their vehicles.

Initially, automakers used platinum as the key catalyst within these devices. But eventually, they turned to another precious metal, palladium, because it has similar properties and it was cheaper—around one-third or one-fourth of the price.

Automakers eventually settled on using platinum within diesel-powered vehicles and palladium within gasoline-powered vehicles, which sapped a lot of demand from platinum since gasoline-powered cars are much more prevalent.

But that wasn’t the only thing working against platinum. Over the past several years, platinum jewelry has gone out of fashion.

Demand for platinum jewelry has fallen by more than half, from 2.8 million ounces in 2012 to 1.3 million ounces in 2022.

So, now you have a sense of why platinum has performed so poorly compared to gold over the past couple of decades. But what could happen from here?

A Mixed Outlook

There’s expectations that over the next few years, platinum demand in the automotive sector might tick up.

You see, a funny thing happened over the past few years. As demand for palladium for use in catalytic converters increased, the price of the metal exploded to the upside. For a few years, palladium was trading at two to three times the price of platinum. Even today, it’s trading at a 33% premium.

Naturally, that is going to cause automakers to substitute platinum in place of palladium in their catalytic converters.

So, that’s good news for platinum in the short-term.

But the longer-term picture for platinum looks more challenging. Battery electric vehicles don’t contain any platinum (or palladium), which means that as consumers increasingly shift towards using those vehicles, demand for platinum (and palladium) may fall.

On the other hand, hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles contain more platinum than traditional gas or diesel-powered vehicles.

There’s been some interest in fuel cell trucks because they have greater range and quicker refueling times than battery-powered trucks. So, if we see growth in fuel cell electric vehicles, that could be a driver of platinum demand growth.

So, the long-term bull case for platinum rests on seeing enough growth in demand from fuel cell EVs to offset the demand lost from battery-powered EVs replacing traditional (internal combustion engine) vehicles.

Okay, so that’s platinum, how about gold?

A Unique Quality

For gold, the investment case is different. Remember, the investment case for gold isn’t dependent on gold’s use in industry because that makes up only a small portion of demand for the metal.

Rather, it’s demand for gold jewelry, and arguably more importantly—demand for gold as an investment and central bank reserve asset—that is going to drive the price of the metal long-term.

Last year, demand for gold from central banks hit the highest level ever*, and demand for gold bars and coins hit the highest level in a decade. In turn, the price of gold got really close to all-time highs.

I expect that dynamic to continue; if central bank and investment demand keep climbing, that should bode well for the price of gold.

Now, you might have noticed that there’s a bit of a self-reinforcing effect when it comes to gold. The price of the metal goes up as more people invest in it, and that high price encourages more investment in gold.

And that’s true. Gold’s value comes from a collective belief that it’s valuable. A lot of people agree that gold is valuable, so gold is valuable.

Not many other assets have this quality. Some of the other precious metals, like platinum and silver, kind of do, but certainly not to the extent of gold.

Gold’s Investment Case

And that’s why I find gold to be interesting. There’s clearly a lot of demand for a safe haven asset that’s uncorrelated with other investable assets. The price of gold tends to do its own thing; it usually doesn’t go up and down with the stock market or the bond market. And that’s a nice feature to have in your investment portfolio.

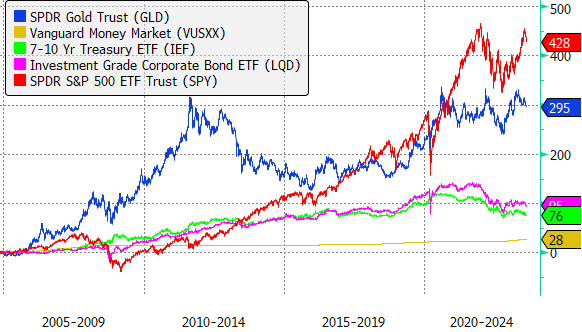

That said, gold isn’t an asset that’s going to deliver eye-popping returns. Since the first U.S.-listed gold ETF, the SPDR Gold Trust (GLD), was launched in 2004, it’s delivered returns of almost 300%, which is equal to an annualized return of 7.5%.

That’s not bad. It’s better than the returns that 10-year Treasuries, T-bills and corporate bonds have delivered. But it’s less than the return for the stock market.

Not to mention, those returns came during a period when gold performed quite well. There’s been periods where it hasn’t done as well—like in the 1980s and the 1990s—when the price of gold was essentially flat for two decades.

So, this is how I see gold: it’s a portfolio diversifier that has the potential to deliver decent returns if you hold it over the long-term, but like any commodity, the timing of your purchase makes a huge impact on the performance that you see.

Personally, gold is not something that I own right now, especially with money market funds yielding over 5%. If I want a safe asset, I’d rather buy those.

But if interest rates go down, then gold might start to look a little bit more attractive versus the other options that are out there, especially if the price of the metal is down.

If we see a 20% or a 30% percent drawdown in gold prices, I might add a little bit to my portfolio (using the SPDR Gold MiniShares Trust [GLDM]) and sell it when prices rebound.

But it’s not the type of asset I’m going to buy and hold forever.

*Some central banks were probably motivated to diversify their foreign exchange reserves away from dollars/euros after the U.S. and its European allies placed aggressive economic sanctions on Russia in 2022