It’s Over: Reflecting On The Disruptive Tech Bubble

In hindsight, it was obvious.

In hindsight, it was obvious. The bubble in the high growth, high valuation segment of the market has burst in spectacular fashion, a meltdown reminiscent of the implosion of dot-com stocks a little over two decades ago. While it’s obvious now that what we witnessed in the second half of 2020 and much of 2021 was a bubble, at the time, it wasn’t as clear cut.

Maybe it should have been.

Looking back, there were obvious signs of excess:

The pre-revenue special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) that doubled or tripled in a day on no news; the meme stocks that went vertical after being touted on WallStreetBets; the ape NFTs and dog coins that were collectively valued in the billions; and the widespread participation of retail investors in the markets, including the Robinhood crowd.

At its peak, pre-revenue Nikola was valued at $29 billion, a sign of the times

On their own, any one of these things could be written off as being among the isolated, whacky market moves that happen every year. But taken together, it was a clear signal that euphoria and FOMO had deeply penetrated the markets.

Memes about “diamond hands” and how “stocks only go up” spread far and wide. Institutional investors, who had dominated the old investment regime, were overshadowed by their retail counterparts, but they too, were swept up in the mania.

Fund companies that traditionally invested exclusively in the public markets began to invest in private markets as well, attempting to buy into hyped-up tech stocks before they would IPO and inevitably soar.

Crossover funds, which invested in both public and private companies, became pervasive. They paid top dollar for stakes in richly-valued private companies ahead of their exits into the even frothier public markets. Any company with a good story in a hot area—fintech, crypto, e-commerce, B2B SaaS, electric vehicles, you name it— was inundated by offers to invest.

In 2021:

•Global venture funding reached $643 billion, double the previous year and up 10x from a decade ago (Crunchbase)

•Nearly 1,000 private companies reached unicorn status, up from 43 in 2013 (CBInsights)

•Close to 400 U.S. IPOs (ex. SPACs) raised $153.5 billion, breaking the $108 billion record from 1999 (WSJ)

•613 SPACs raised $162 billion—more than the previous ten years combined (SPACInsider)

Yet, as many red flags as there were, in the midst of the bubble, it didn’t seem like it would end anytime soon. Like with all bubbles, a series of powerful narratives lent credibility to what was going on.

In the 90’s, it was that the internet was going to revolutionize everything. In the 2000’s, it was that new financial products had unlocked housing demand for millions of new people. These narratives aren’t always wrong—often there’s at least some truth to them—but when they lead to asset prices becoming unhinged from fundamental values, that’s when you get a bubble.

This time around, the initial spark was the pandemic and the lockdowns that followed. Covid created a massive shift in economic activity from the physical world to the digital world. Demand for everything from e-commerce to video games to streaming to B2B software accelerated overnight.

"We’ve seen two years' worth of digital transformation in two months,” Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella famously said in April 2020. Meanwhile, communications software provider Twilio said that the pandemic had accelerated its customers’ adoption of digital technologies by six years, and consultant McKinsey noted that e-commerce penetration had accelerated by ten years in three months.

All of this gave us a sense that the pandemic had shifted the paradigm—a once in a hundred-year virus had created a once in a hundred-year opportunity for investors. Many of these technological trends were already on an upward trajectory before 2020, which made it easy for them to become turbocharged once the pandemic hit.

The other narrative the drove the bubble came about from the government policy in response to the pandemic. As central bankers around the world lowered their benchmark interest rates to zero, investors extended themselves further out on the risk spectrum.

With risk-free rates at zero, the future value of cash flows was worth significantly more than it was before, especially for growth stocks, which derive the majority of their profits in later years. This gave investors fundamental cover for bidding asset prices ever higher.

That’s always the case with bubbles, isn’t it? One or more extremely compelling narratives give investors the sense that there’s been a paradigm shift, that things are different this time. This has investors believing that valuations that are much higher than normal are warranted.

So, while the obvious ridiculousness of certain meme stocks and SPACs going up could be brushed off, the same sort of skepticism wasn’t usually applied to more solid businesses. The work-from-home cohort of stocks—DocuSign, Zoom, Peloton, and others— were case in point.

Few raised an eyebrow at their valuations because their businesses were growing enormously thanks to the pandemic at the same time that interest rates were at all-time-low levels.

Valuations of 30x, 40x, or 50x sales became commonplace, and it was all justified based on the idea that the pandemic had changed everything and rates were going to stay low forever. In this environment, profits didn’t matter, only growth did.

But like any mania, it couldn’t go on forever.

Cloud enterprise value-to-revenue multiples

Source: Meritech

The first cracks in the growth bubble started to form in early 2021. That’s around the time that the first COVID vaccines began to roll out and people started to see a pathway towards a normalization of the economy and life in general.

A lot of biotech stocks topped out at this time, and so too did the ARK Innovation ETF (ARKK). The fund was a posterchild for the excesses of what could aptly be named the “disruptive tech bubble.” I like the term because it encompasses a bunch of areas, all of which benefited from the profligacy of the time, including EVs, software, biotech, cryptocurrencies and nonfungible tokens (NFTs).

ARKK had $28 billion in funds under management at its peak, a 20-fold increase from a year earlier, and was managed by Cathie Wood, a ubiquitous presence across the financial media for much of the past few years.

Her ETF was known for taking aggressive bets on what she called disruptive technology stocks—most famously Tesla, but also pandemic darlings like Zoom, Roku and others. ARKK topped out on February 12 after rising 350% over the preceding 11 months.

ARKK lost about a third of its value between February and May before stabilizing, but the party in disruptive tech was far from over. Many pockets of the disruptive tech universe continued to inflate unabated. Crypto and the metaverse became super hot topics over the summer and into the fall, igniting massive rallies in everything NFTs to shares of Roblox. This phase of the bubble reached a crescendo on Oct. 28, when Facebook announced it would be changing its name to Meta to reflect its metaverse ambitions.

That nearly marked the peak of the bubble; prices rallied a bit more until November 9, after which the bubble began to burst.

Though bubbles sometimes burst spontaneously, just as often, there is a trigger.

In the case of the disruptive tech bubble, that trigger came from macroeconomic factors. For months leading up to the top, a combination of factors, including supply chain bottlenecks and the post-pandemic reopening of the economy, had led to surging prices for goods and services. Inflation all around the world was running at multidecade highs.

Yet, central bankers assured investors that the issues causing inflation would abate quickly; the U.S. Federal Reserve famously used the term “transitory” to describe the price pressures, a characterization that investors eagerly bought into for much of 2021.

That all changed in November. After inflation took another leg up that fall, Fed chair Powell shocked markets when he told Congress that the word transitory was no longer an appropriate way to describe inflation, scrapping the word he and his fellow central bankers had used just weeks earlier at their policy decision meeting.

The reaction was immediate; stocks tumbled, led by the bubbly high growth segment of the market. Powell was setting the stage for an aggressive set of rate hikes, though at the time, he nor the markets understood just how aggressive those hikes would end up being.

The air began to be let out of the bubble, gradually at first, and then faster and faster as the market began to realize that inflation would be a much tougher beast to slay than it had anticipated. It’s a battle that continues until this day, though there are hopes that consumer price pressures could be peaking.

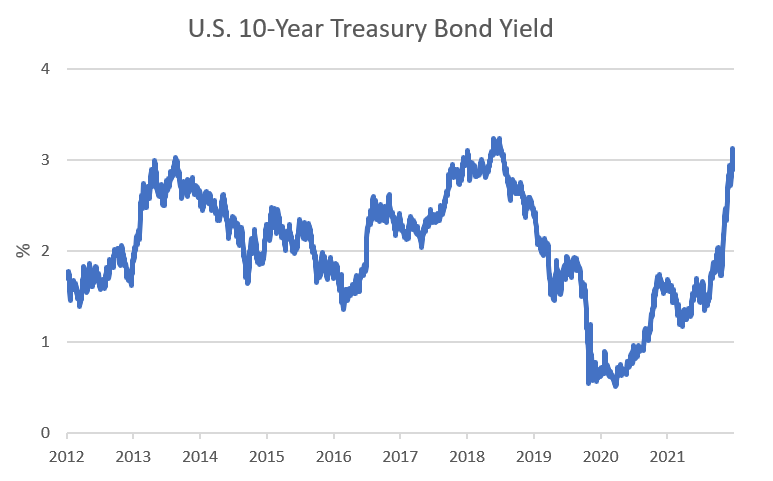

Markets and the Fed anticipate raising rates to 3% or more, a level that is already reflected in Treasury bonds.

The higher rates have completely removed a key pillar of the narrative that drove the disruptive tech bubble— that low rates would support high valuations. Now rates are not only not low, they are around their highest levels in four years, with the potential to break out to their loftiest levels in more than a decade if inflation is not contained swiftly.

At the same time that the rates-valuation narrative crumbled, the other pillar of the disruptive tech mania also reeled. It’s become increasingly clear that the pandemic didn’t create a paradigm shift in the demand for digital technologies after all; it merely pulled forward demand from the future.

E-commerce, streaming video, digital ads, and even B2B software have all seen marked slowdowns in their growth rates. Some companies that misread the demand environment and made poor operational and investment decisions, such as Peloton, find themselves in even worse shape than if the pandemic had never happened.

With higher rates and a more normalized demand environment, valuations have reverted to the mean. Because valuations were so high in 2021, that’s led to painful drawdowns in many stocks. The aforementioned ARKK fell 76% from its highs over the past 15 months, mirroring the losses in the Nasdaq-100 in the aftermath of the dot-com bubble.

The WisdomTree Cloud Computing ETF (WCLD) is down 59% since its November peak, though individual software stocks have plunged 70%, 80%, 90% or more.

As I write this, the sell-off is still ongoing and it remains to be seen where and when these former high flyers bottom out.

Though high inflation and interest rates were the catalysts that burst the disruptive tech bubble, it’s likely that valuations would have retreated no matter what. Sure, maybe the drawdown wouldn’t be as severe as it’s been if rates had stayed low, but directionally, things would have probably played out similarly.

It’s never “different this time.” Market valuations have risen over time, but only gradually. Investors should be suspect of valuations that become unmoored from historical levels. The most profitable businesses ever created—Google, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft— traded at relatively prosaic multiples for much of their public market lives. As an investor, you didn’t have to strain credulity to justify the valuations.

Once in a while there could be a stock whose growth is so strong and so durable that it can support an eye-popping multiple for a while, but that’s a rare exception (Amazon comes to mind). When you see dozens of stocks in the same boat, it’s time to be wary.

I get it, though. In the heat of the moment, when everything is going right, it’s hard to stay level-headed. FOMO is real and it’s hard to avoid the siren call of quick gains, especially in an exhilarating bubble environment.

Don’t get me wrong: I am still extremely bullish on many of the new technologies that came to the forefront during the past couple of years. The metaverse, the cloud, and crypto, aren’t going away. These are still exciting areas with a ton of growth potential. But if you’re going to invest in these spaces, you have to be more discerning about the price you pay for the assets you buy.

The bubble has popped; welcome to reality.