South Korea's Population Collapse

South Korea just broke a global record that the country probably didn’t want to break.

South Korea just broke a global record that the country probably didn’t want to break.

We just got data that showed that the country’s fertility rate dropped to 0.78 in 2022, which is below the previous record-low of 0.81 set in 2021 by none other than South Korea.

So yes, the country just broke its own record.

And in case you’re not familiar with the term, the fertility rate is the average number of children that a woman is expected to have in her lifetime based on birthrates in a given year.

In other words, the typical woman of child-bearing age in South Korea today is expected to have either one child or no children, something that could have dramatic consequences for the country’s population.

You see, just to keep its population stable, South Korea’s fertility rate needs to be at least 2.1 (assuming no immigration). That’s called the replacement rate because that’s enough children to “replace” the parents and to account for a small number of children who don’t survive until adulthood.

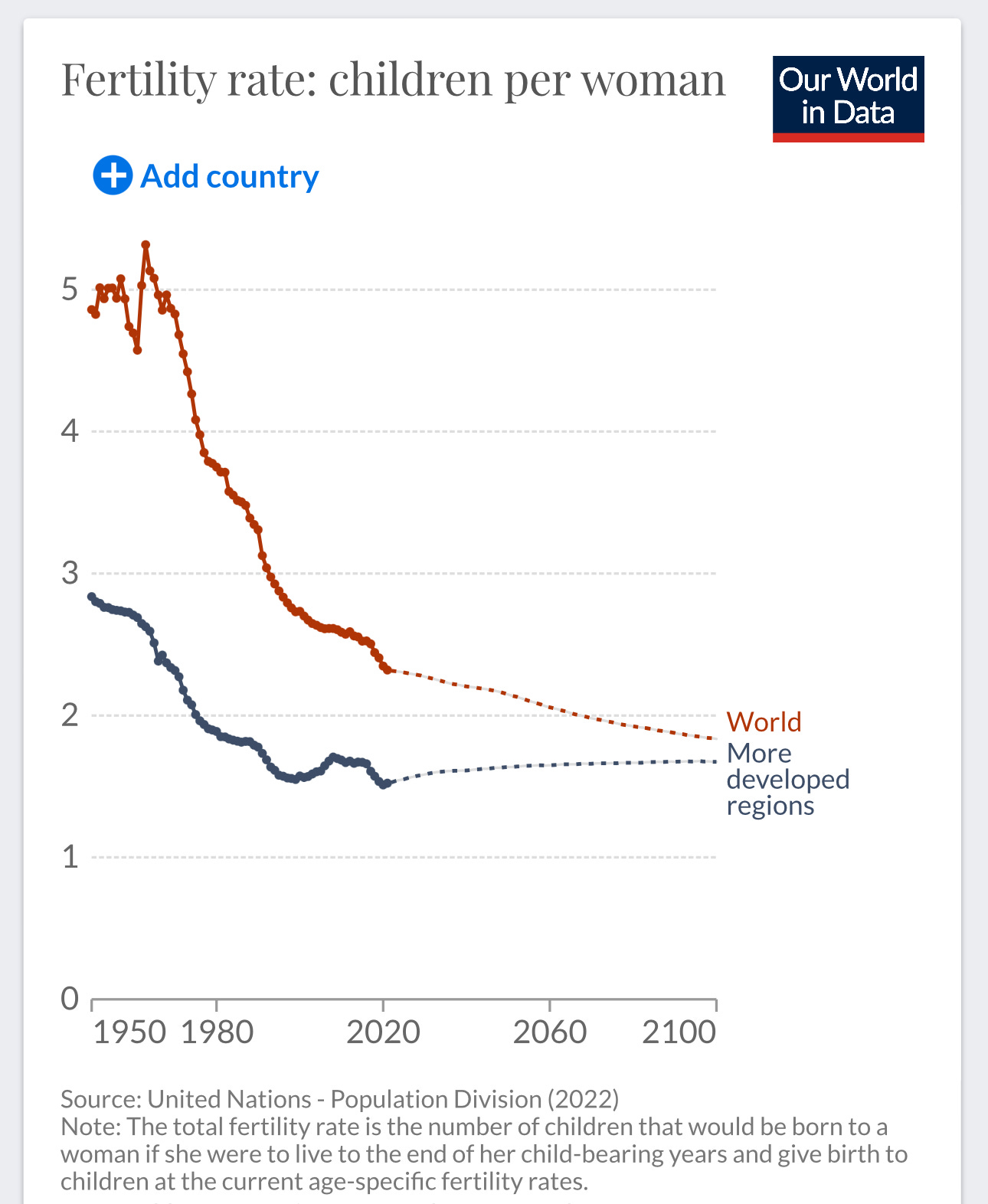

Now if you go way back in the day, almost every country in the world had really high fertility rates—5 to 7 children was pretty typical.

But as countries modernized and became richer, women had fewer and fewer kids. There’s many reasons for that, but it boils down to women having more education and more employment opportunities, combined with the fact that it’s become more expensive to raise kids.

In developed countries, fertility rates have trended down towards the replacement level over time.

And in some cases—like in much of Europe and East Asia—they’ve even fallen below the replacement level. In fact, today, almost half of the world’s population lives in countries where fertility rates are below the replacement level.

This is significant because unless a country has immigration to offset it, a fertility rate that’s below the replacement rate will eventually lead to a declining population.

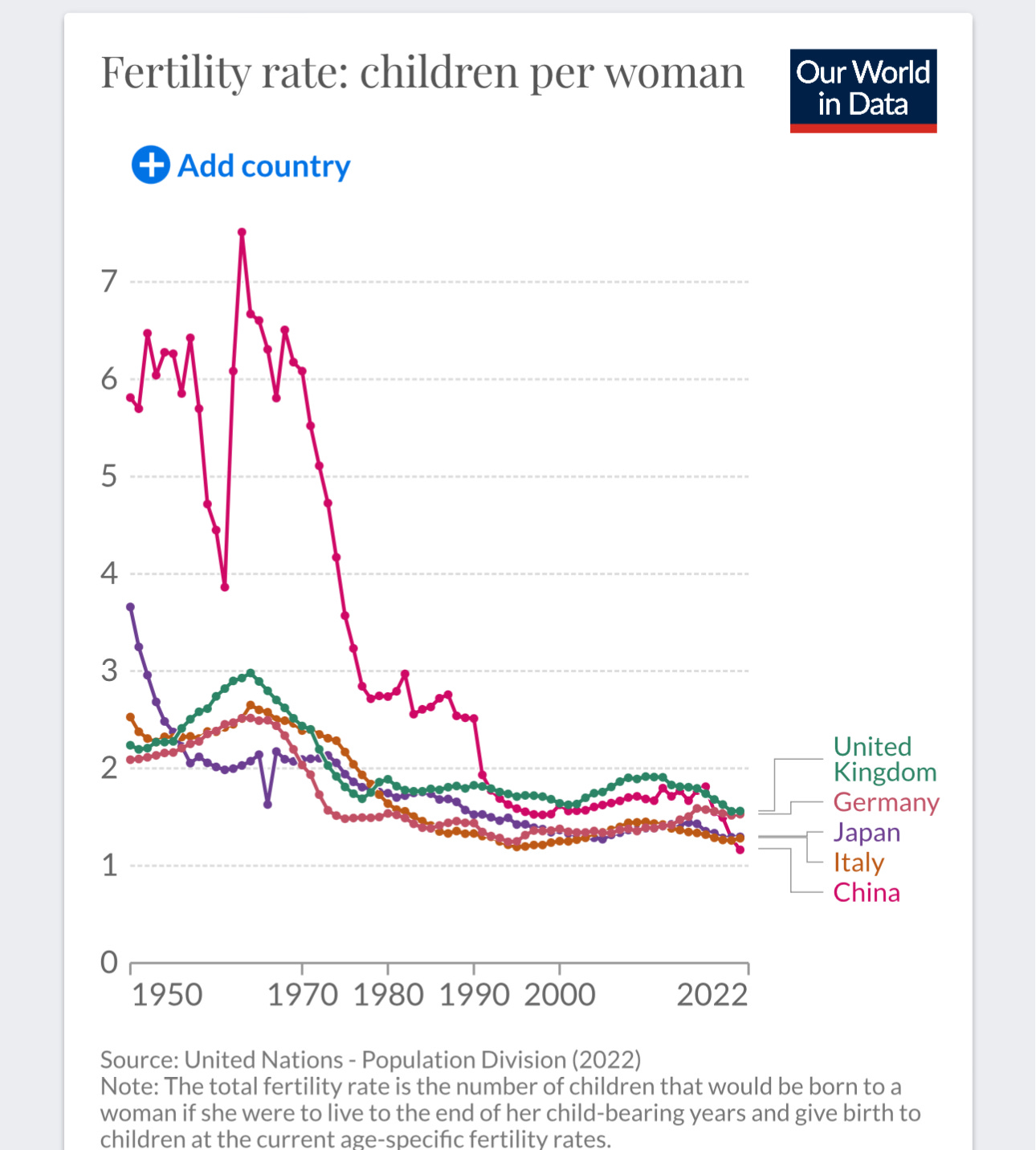

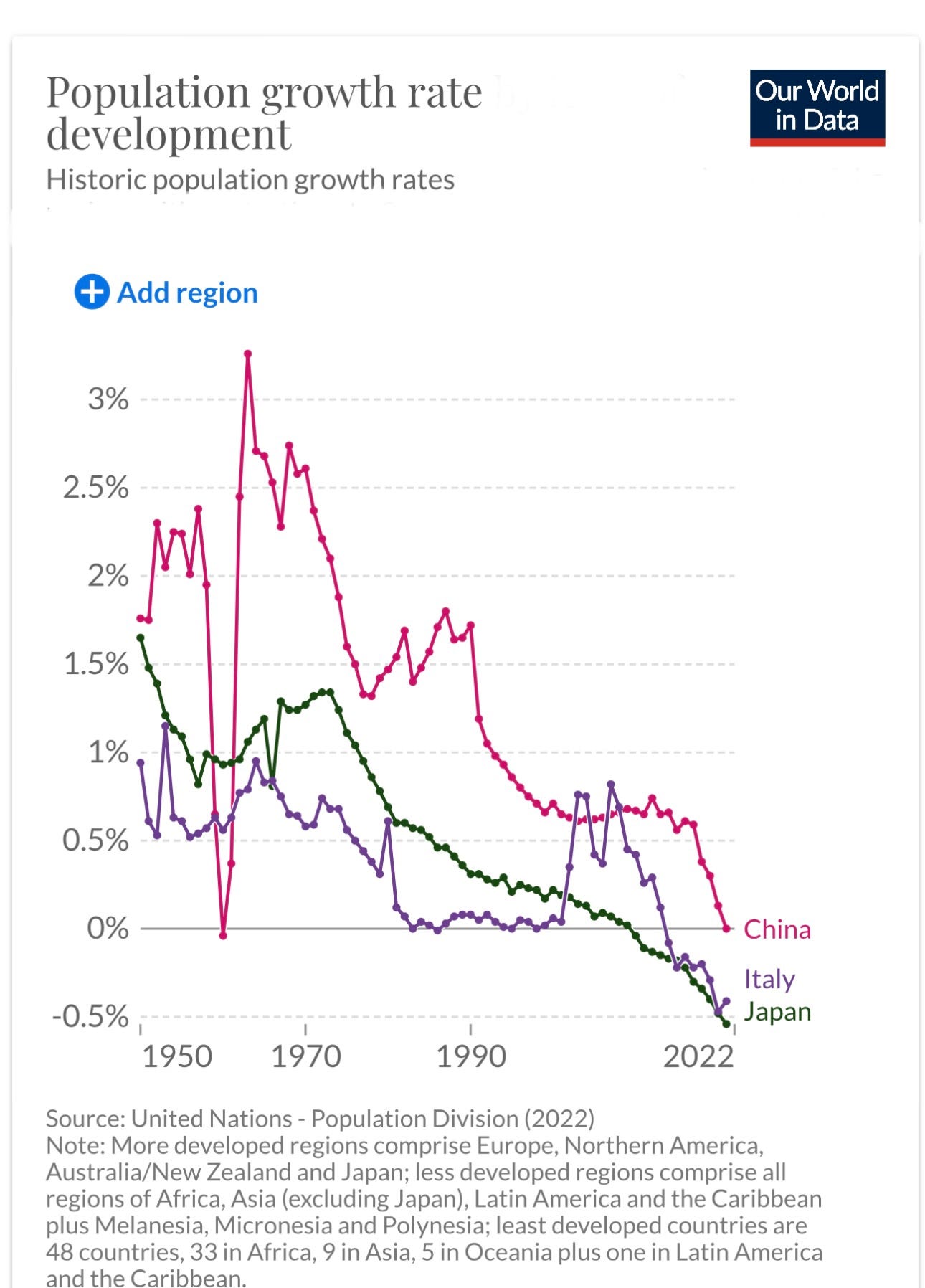

And that’s exactly what we’ve seen in countries like Italy, China, Japan and many others.

But to have a country with a fertility rate that is just slightly below the replacement rate is one thing. In that case, the population will decline slowly.

It’s a completely different thing to have a fertility rate that’s way below the replacement rate—like South Korea has. In that case, you could see a population collapse.

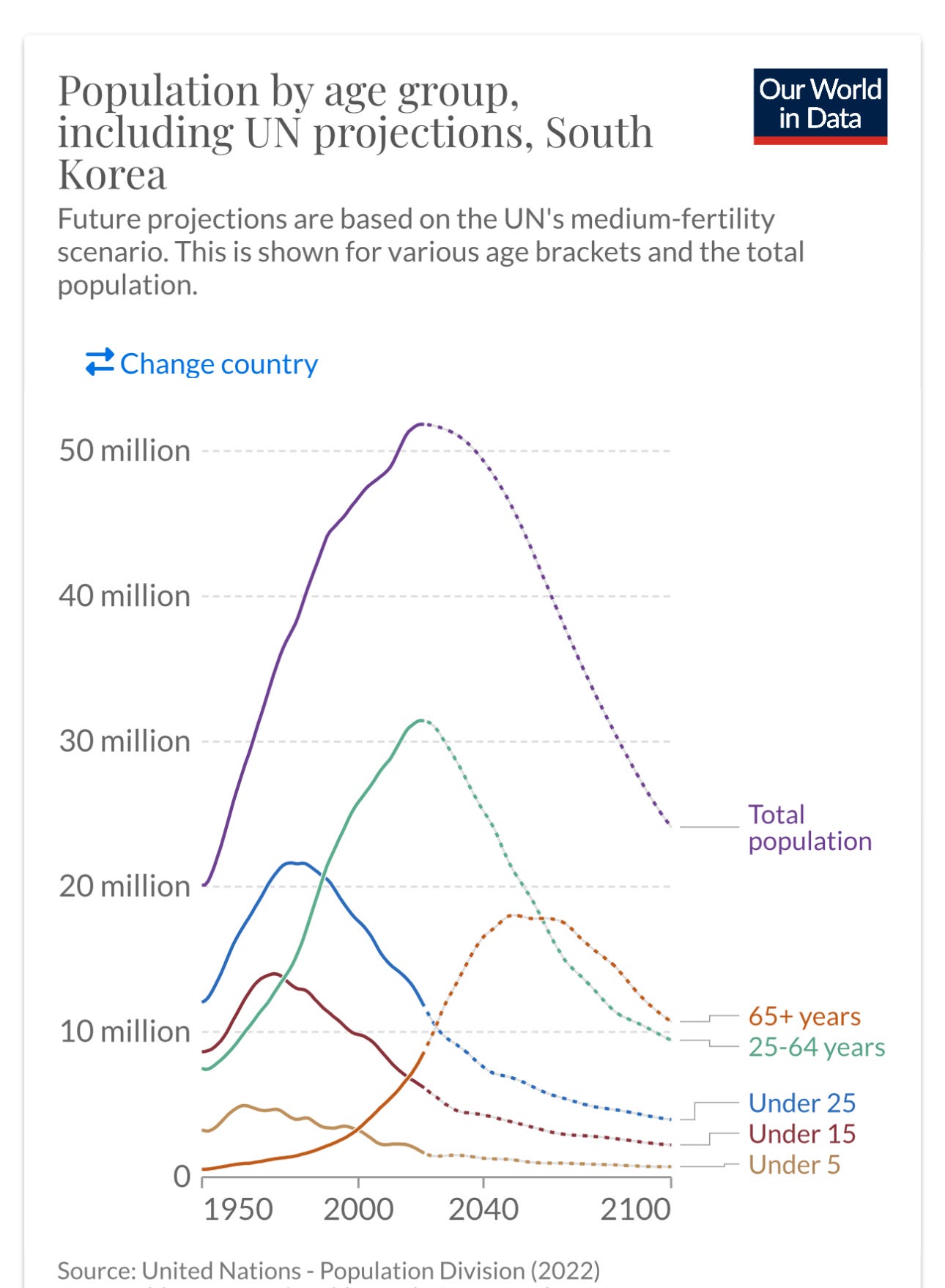

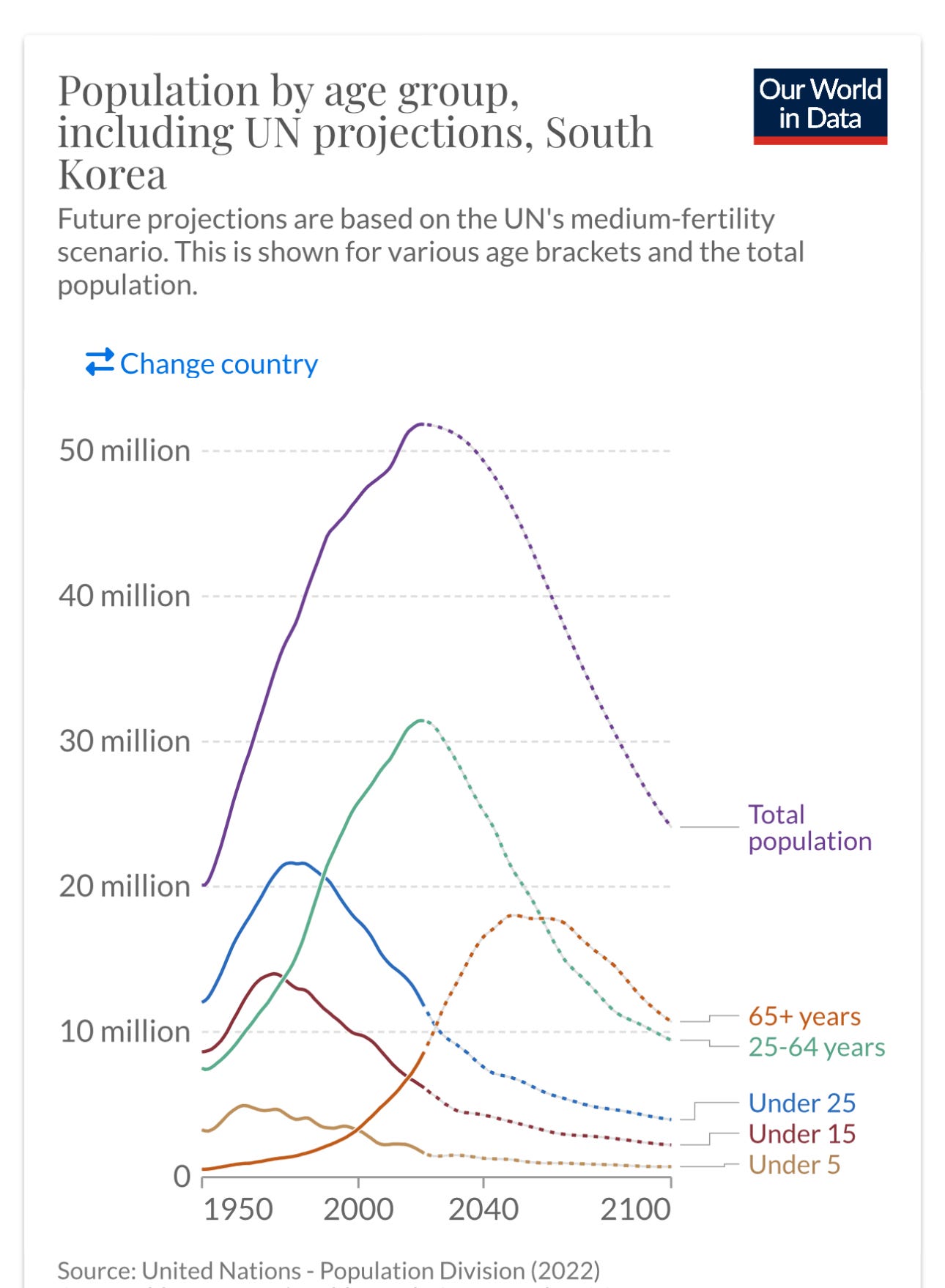

And if you look at the projections for South Korea’s population, that’s essentially what could happen. The number of people in the country is expected to fall by half by the end of the century, according to the United Nations.

A declining population might not seem like a big deal, but there are potentially some major issues that come with that. The biggest one is the impact on the workforce, the economy and on social programs.

As South Korean women have fewer children, that’s going to eventually lead to fewer working age people in the country.

As you can see from this chart, the number of people in South Korea aged 25 to 64 and under the age of 25 are forecast to fall by two-thirds by the end of the century.

Fewer workers means that the size of the South Korean economy will be smaller than it otherwise would be.

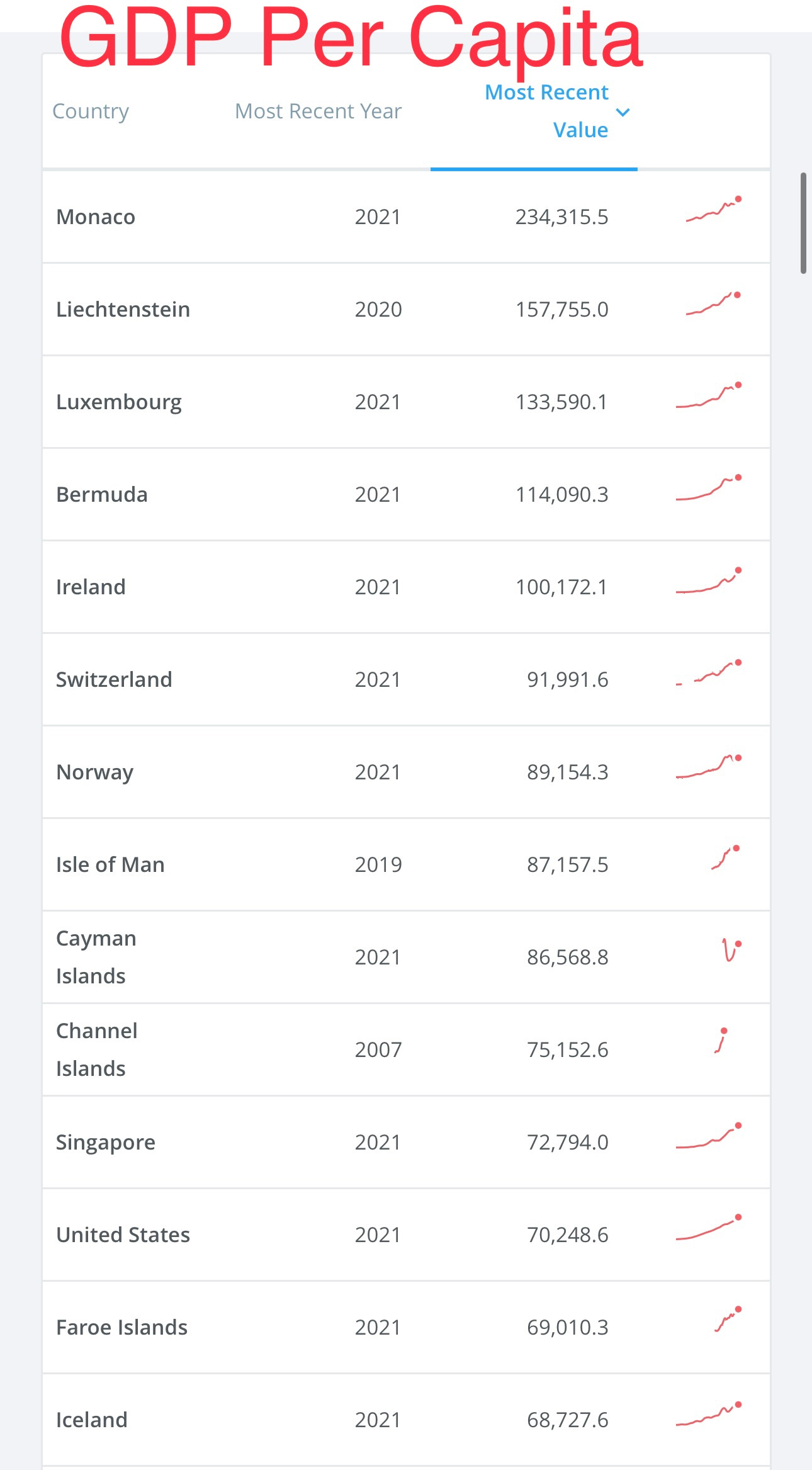

A smaller workforce isn’t necessarily a negative for peoples’ standard of living in and of itself. There are a lot of small, rich countries in the world that are doing just fine.

But you got to remember that South Korea is an export-reliant economy. If those industries can’t find the workers they need, that could reduce their competitiveness, and by extension, the broader South Korean economy.

To me, the bigger issue is one related to age structure.

What I mean by that is as its population declines, South Korea is likely going to have fewer working age people relative to older, nonworking people.

You can see that the population of people over the age of 65 is expected to more than double over the next three decades.

That means that there will be fewer working age people available to support a growing population of elderly people.

As a result, South Korea’s social welfare programs could be strained.

In January, South Korea’s national pension service forecast that the country’s main public retirement fund would run out of money by 2055.

To fill the gap, the government might have to borrow money, increasing the debt of the nation.

This is why the South Korean government is trying to get people in the country to have more children.

President Yoon Suk Yeol has called the country’s low fertility rates a national “calamity” and his administration has provided incentives for families to have children. The government is offering a monthly allowance of 1 million Korean won, or $770, to parents with babies up to 12-months-old.

So far, it hasn’t worked. People who follow these trends closely point to several cultural and economic forces that are keeping South Korean women from having more children.

There are things like the high cost of raising kids. South Koreans spend an average of six years of wages per child on education-related costs, according to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

Housing costs are astronomical as well, with Korean home prices recently reaching 18x the average annual income, up from 10x a decade ago, per Bloomberg.

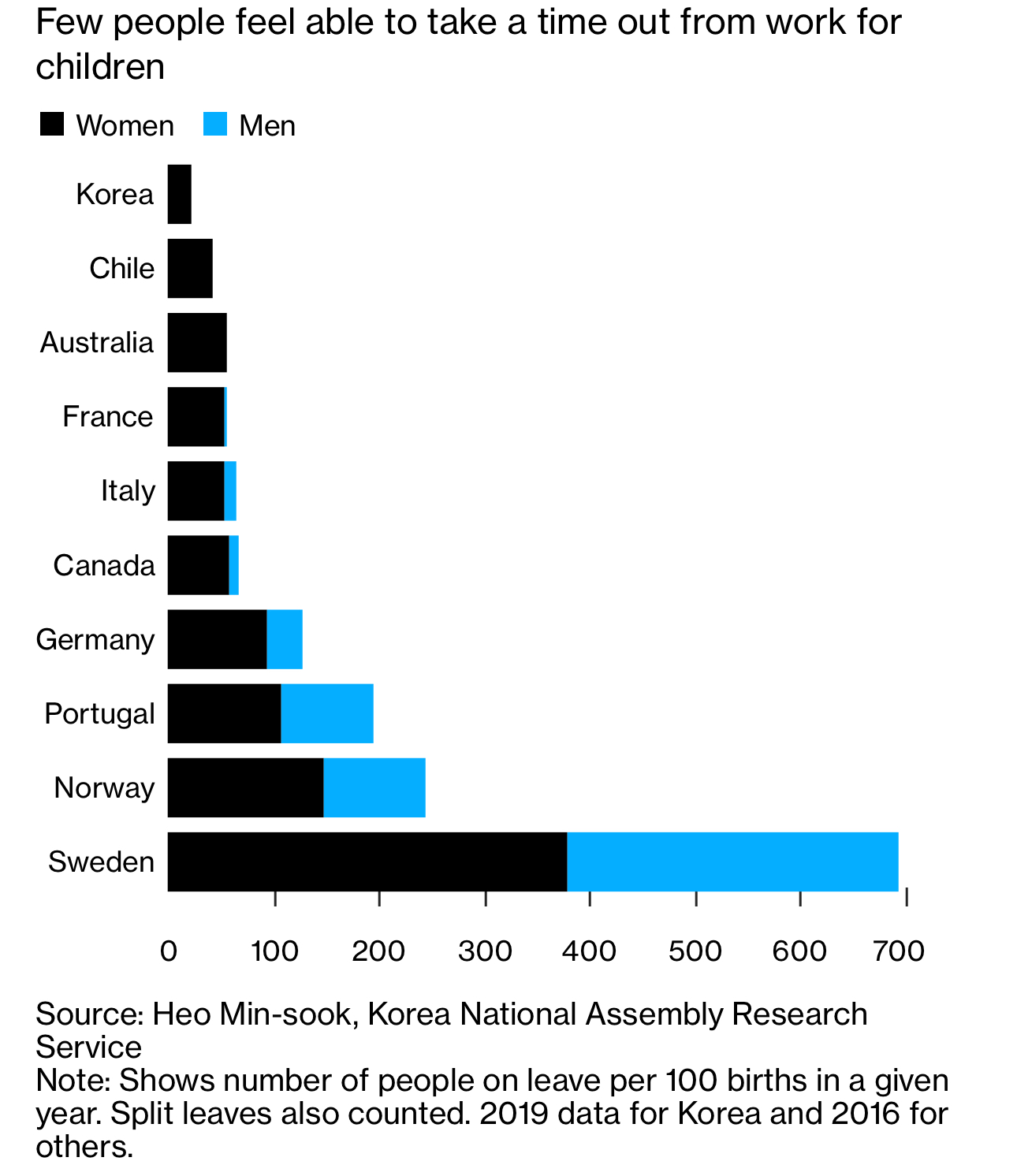

There’s also pressure from employers to work long, grueling hours with limited time off, even to take care of babies. At the same time, childcare services are difficult to find and extremely expensive.

All this has made it increasingly unappealing for South Koreans—particularly South Korean women who do most of the work of raising children—to have kids.

So we’ll see what happens. Maybe some of these cultural and economic norms will change or maybe the government will be successful in incentivizing families to have more children.

Or maybe not.

Other options are to increase the workforce by allowing more immigration. Over the past couple of decades, South Korea has relaxed its immigration policies and invited more foreigners into the country.

But immigration remains a controversial topic in the country and South Korea’s population still remains largely homogenous.

Another option is to use technology and automation to replace the workers that will be lost due to population decline.

We are seeing some really big technological changes happening today so maybe a declining population won’t be as much of a challenge in the future thanks to technology.

Other countries like Japan, Singapore, and Germany are facing similar issues as South Korea, so this is going to be an interesting area to watch.