The Commercial Real Estate Crisis

It could have dire consequences for landlords, banks, local governments, and potentially the economy at large.

San Francisco is ground zero for a crisis that’s gripping cities across America and beyond.

It’s there that the owner of this $500 million building recently defaulted on its mortgage.

This type of thing is happening with increasing frequency not just in San Francisco, but in many other cities as well. And it could have dire consequences for landlords, banks, local governments, and potentially the economy at large.

Here’s everything you need to know about the commercial real estate crisis.

Permanently Altered

Take a stroll through San Francisco’s financial district midday on a Thursday and you’ll notice something strange: there’s not a whole lot of people there.

It’s strange because up until a few years ago, it was usually pretty busy in what’s essentially the city’s main commercial area.

But in 2020, something happened that changed everything: the pandemic.

The pandemic’s impact on the economy and our lives has diminished over the past couple of years. Most people hardly even think about it anymore.

But there’s one area where the pandemic has permanently altered the way many of us live our lives.

Starting in 2020, millions of office workers began working remotely, leaving giant office buildings, like those in San Francisco’s financial district, empty.

At the height of the pandemic, nearly 60% of work in the United States was done at home. Some workers, such as those in the tech industry, worked completely remotely.

Once the pandemic ended, people started slowly going back to offices, but things are still nowhere near what they were—and it’s unlikely we’ll ever go back to the way things were before the pandemic.

Today, about 12% of full-time employees work from home exclusively, while another 29% have hybrid work arrangements, where they work some of the time on-site and the rest of the time at home (overall, around 28% of work today is done at home, compared to 5% prior to the pandemic).

There’s a lot of debate about whether a fully remote, a hybrid or a fully on-site work arrangement is the best.

There’s probably no right answer. It depends on the job, on the person and on the company in question.

But regardless, we’re in a new world in which working from home is going to be much more prevalent, especially for white collar office jobs.

And that means that office buildings are going to be utilized much less than they were before.

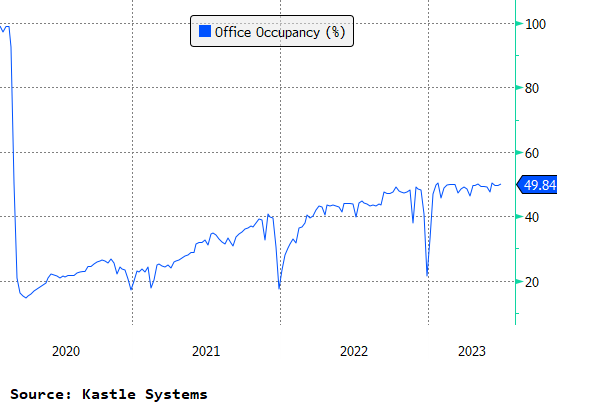

If you look at the latest office attendance data, currently, the average office is only at around 50% capacity on any given day.

That’s a lot of unused office space—too much office space.

That’s why companies have been moving quickly to reduce the amount of office space that they lease, either by subleasing space to other tenants or by letting their leases expire when they come up for renewal.

Some are even taking a more aggressive approach. Twitter, which is headquartered in San Francisco, hasn’t been paying its rent this year. Word is that the company wants to renegotiate its lease with its landlord to save some money (the landlord responded with a lawsuit).

So, it’s pretty clear that demand for office space is declining significantly.

But owners of office buildings—like Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), private equity firms, and others— aren’t the only ones who will be impacted by this.

Fewer tenants mean less revenue from rents, which makes it more difficult for landlords to pay back the loans that are backing these buildings.

You see, just as individuals and families use mortgages to purchase their home, most commercial real estate is financed using loans as well—either bank loans or things like commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), where money is raised from investors.

So, less rent revenue means less money to pay back loans, and naturally, that’s going to cause a larger number of building owners to be delinquent on their loan payments or to outright default.

That, in turn, is going to hurt lenders like banks and investors in CMBS.

Urban Doom Loop

Another group that is going to be hurt by this is local governments. In cities across America, property taxes make up a big chunk of local governments’ revenues.

In New York City, property taxes on office buildings make up 10% of the city’s total tax revenues.

Meanwhile, the businesses that surround office buildings— like restaurants, convenience stores, and other shops— will also feel the effects of the decline in office attendance. Less foot traffic around office buildings will result in the loss of billions of dollars of potential sales.

Public transportation systems will be strained as well. Fewer days in the office means less time commuting on trains and buses.

In fact, many transportation agencies in the U.S. are already facing steep budget shortfalls because of reduced ridership.

As a result, they’re considering cutting services and reducing operating hours, which are things that will make them even less attractive to riders.

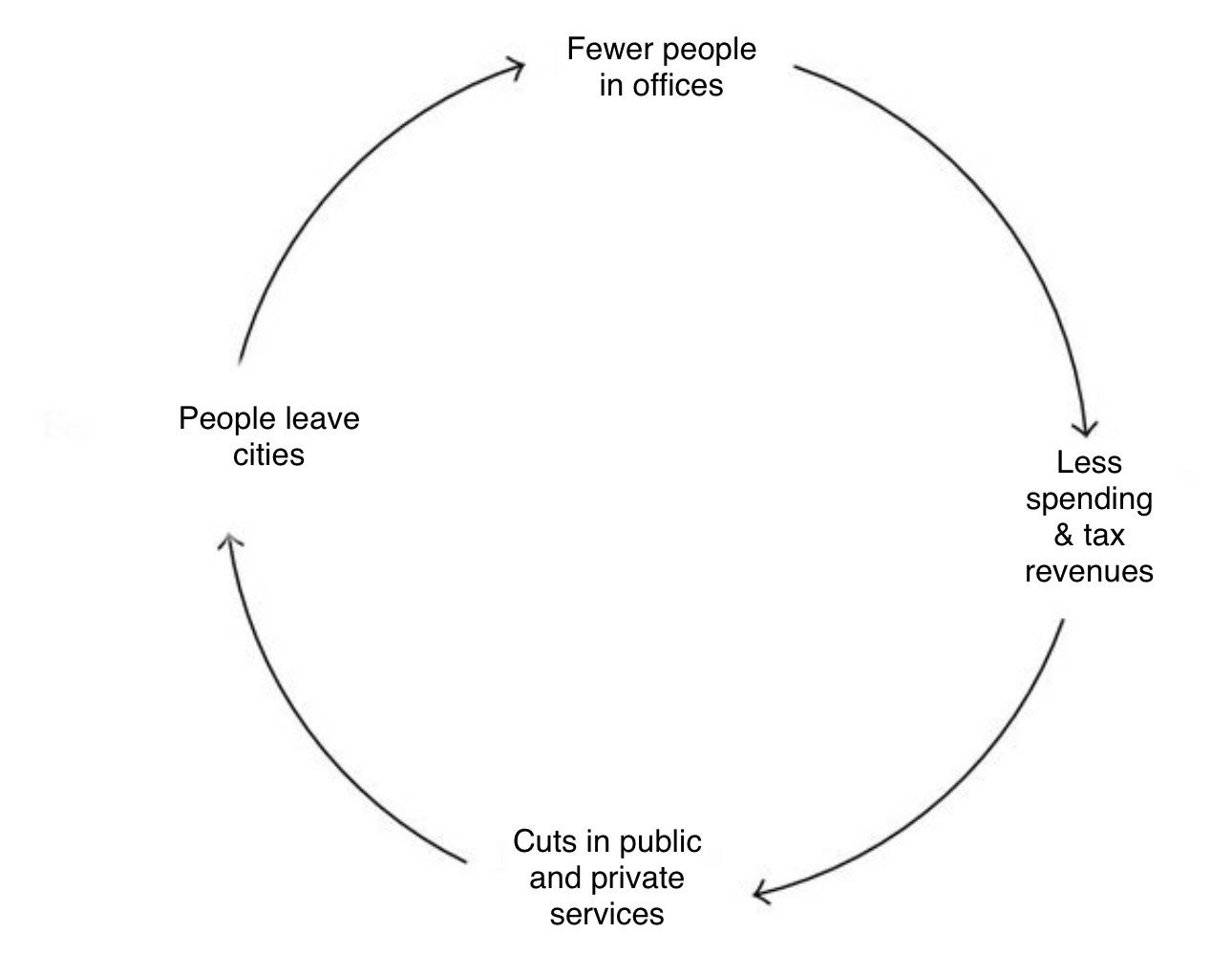

This cycle— where fewer people in offices leads to less spending and tax revenues, which then leads to cuts in public and private services, which ultimately leads to people spending less time in cities— is what some people are calling an urban doom loop.

It’s the reason why the mayors of New York City and San Francisco have called for workers to return to offices. In some cases, they’ve even pushed employers to force their workers to come back in (“you can’t stay at home in your pajamas all day,” NYC mayor Mayor Eric Adams, said last year).

But their pleas have largely fallen on deaf ears. Remote working is here to stay, and cities have to adapt to this new reality (even the mayors are slowly coming to this realization).

The Worst is Yet to Come

The bad news for all of the parties impacted by this is that things aren’t going to get better anytime soon; in fact, they’re probably going to get worse.

The truth of the matter is, we haven’t felt the full impact of the work from home phenomenon on commercial real estate yet.

The average office lease in the U.S. is seven years. So even though companies want to reduce their office footprints, they haven’t been able to yet because they’re locked into leases.

Remember how I said that the average office is only half full today? Well, the vacancy rate—or the percentage of office space that doesn’t have a lease— is 20%.

That’s a record high vacancy rate, but based on office attendance, it seems like that rate could go even higher in the future.

As leases come up for renewal, more and more companies are going to let them expire, leading to higher vacancies.

Unfortunately for building owners, their problems don’t end there. The plunge in demand for offices due to more people working from home is already a massive headache for them.

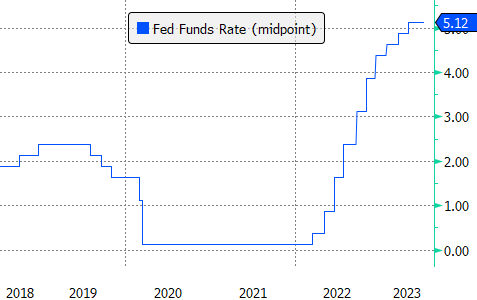

But this couldn’t have come at a worse time. Over the past year and a half, interest rates have gone through the roof in response to elevated levels of inflation.

Higher interest rates increase borrowing costs for building owners and they lower property values as well*.

So, this is a terrible combination for landlords. Their borrowing costs are going to go up at the same time that their rents and their property values are going to go down.

The full effects of this will be felt when it comes time for building owners to pay back their loans.

Many will be unable to pay them back. And whereas in the past they might have been able to refinance their loans to give them more time, high interest rates could eliminate that possibility.

Analysts at MSCI estimate that $155 billion worth of U.S. commercial real estate could face financial troubles in the next few years.

The Economic Fallout

When a building owner defaults on its loan, that kicks off a foreclosure process by which the lender will try to recoup its money by selling the property**.

Banks finance 40% to 60% of commercial real estate in the U.S., so they’re the ones who are going to be left holding the bag when landlords can’t make their payments.

In many cases, they’ll end up selling these properties at extremely depressed prices.

One report from researchers at NYU and Columbia University suggests that office property values might decline by 44% from their peak levels by the end of this decade. Another report from analysts at Capital Economics says that prices could tumble by 35% by 2025.

That would be a big hit for any banks holding onto these properties. And because banks are so fundamental to our financial system, their troubles could spread to the rest of the economy if they dramatically pull back on lending (that’s essentially what happened during the global financial crisis in 2008).

A Rosier Outlook

But it’s not all doom and gloom. There are rosier projections that paint a much more optimistic picture for office buildings.

The commercial real estate services firm Cushman & Wakefield predicts that there will still be plenty of demand for office space in the future as companies adapt to a hybrid work environment.

They believe that there will be 330 million square feet of excess office space by the end of the decade. But that’s not a huge amount when you compare it to 5.68 billion square feet of total office inventory that they expect there to be at that time.

Analysts at the firm think that high-end, modern office buildings with a lot of amenities will have no problem finding tenants.

On the other hand, older, generic buildings with few amenities will have the most trouble attracting tenants.

Longer-term, a solution for those older buildings is for them to be converted— either into other types of commercial properties for which there is a lot of demand (like health care facilities)—or into residential properties (like apartments and condos).

That is essentially the playbook that New York City has used in the past when demand for office buildings has faltered. According to one estimate, about 40% of the residential units built in lower Manhattan over the past three decades were the result of office building conversions.

That said, even though converting offices to residences sounds like a good idea, it isn’t something that’s easy to do. Zoning restrictions, high costs, and floor plates that aren’t conducive to residential use make converting some office buildings difficult, if not impossible.

So, we’ll see what happens. There’s no sugarcoating it: the next few years will be challenging, especially for owners of lower quality office buildings, the businesses that surround them, the banks that lend to their owners, and city governments.

But this doesn’t necessarily have to become an economy-wide crisis. After all, we know what’s coming, so there’s time for the affected parties to prepare.

That time and foresight reduces any potential negative fallout on the broader economy.

Another thing I’ll note is that there are some parallels between what we’re seeing with office buildings today and what we’ve seen in another part of the commercial real estate market: retail.

Over the past decade and a half, many brick-and-mortar retailers have struggled due to competition from e-commerce.

Even today, we’re seeing the effects of that, with the bankruptcy of Bed Bath & Beyond, Party City and others.

But despite the retail industry’s struggles, there’s still demand for brick-and-mortar retail properties (the vacancy rate for retail-focused commercial real estate has been steady around 10% during the past decade, according to Moody’s Analytics).

The same will probably be true of office buildings. We might not need as much office space in the future, and some of the older buildings might need to be renovated or converted to soak up some of the excess inventory, but eventually, a new equilibrium will be reached.

*Commercial real estate is often valued by estimating a property’s net operating income and dividing that by a capitalization rate. Cap rates are based on the risk-free interest rate and investors’ perception of the riskiness of the property (riskier properties have higher cap rates).

**Alternatively, the lender and owner could try to reach some sort of renegotiated loan agreement.