The Demographic Transition

The world is in the midst of a major population shift.

From the year 10,000 BC to the year 1700, the world’s population increased extremely slowly—only 0.04% per year.

Then over the next 400 years, the number of people on Earth exploded, rising 20x faster, from 600 million to 8 billion today.

Believe it or not, this population explosion is coming to an end.

The world’s population may never exceed 10 billion, and even if it does, it probably won’t go much higher than that.

The reason for that is a phenomenon known as the demographic transition.

This is a four-stage model of population growth that country after country has gone through.

Here’s what those four stages are:

In stage one, a lack of food and high levels of disease result in a low life expectancy. Birth rates are really high, but so are death rates. Consequently, a country’s population is stagnant or grows only very slowly.

This was the state of world for most of human history.

Then comes stage two, which is where human health improves. More food, better sanitation, and improvements in medical care lead to a fewer number of deaths.

But here’s a key point: while death rates quickly decline in stage two, birth rates remain high because the cultural and economic forces that push parents to have lots of kids remain in place.

The combination of high birth rates and falling death rates leads to a rapid increase in a country’s population.

In stage three, birth rates start to decline as women get more access to education and career opportunities, and the cost of raising children rises as well. This reduction in birth rates leads to slower, but still positive population growth.

Finally, in stage four, the birth rate drops even further, matching the death rate for the first time since stage one.

In turn, the population stagnates again, only this time it’s because of low birth rates rather than high death rates. In some countries, the birth rate even falls below the death rate, which leads to a declining population.

We’ve seen these four stages play out in country after country and it’s the reason why demographers can safely predict that the world’s population will peak sometime in the next several decades.

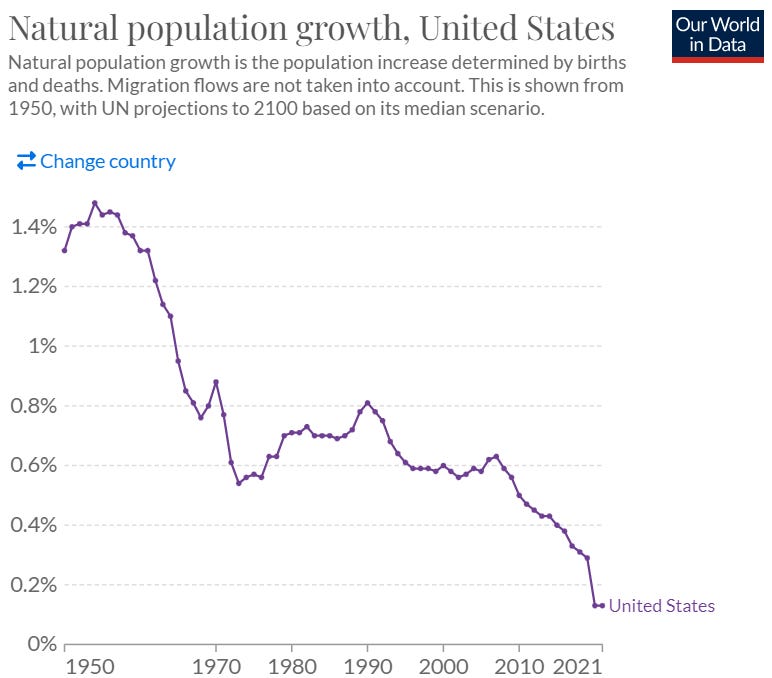

Today, most rich, developed countries are sitting at stage four. Their populations are flat or even falling.

On the other hand, developing countries are in anywhere from stage two to stage four of the transition.

Last year, China’s population outright fell, meaning that it’s very much in stage four.

On the other hand, India, which became the world’s most populous country this year, is still seeing its population grow, though at a declining rate—putting it at stage three.

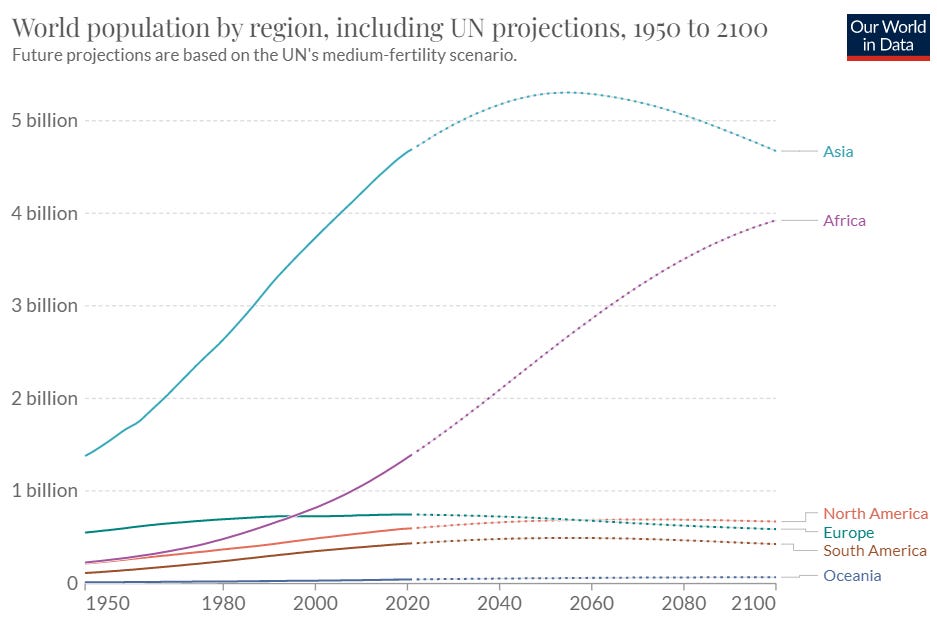

If you look at the data, most regions of the world are close to the point where their populations are going peak.

Europe is already past its peak, while North America, South America and even Asia aren’t that far from reaching their peaks. All three of those continents are expected to see only around a 10% increase in their populations over the next few decades.

The only major region where we’re likely to see significant population growth going forward is Africa.

But here is also where the most uncertainty about the world’s population lies.

The United Nation’s base case projection calls for Africa’s population to triple to 4 billion by the end of this century.

On the other hand, the Wittgenstein Centre projects that the continent’s population will only double to 2.6 billion.

In the UN’s projection, the world’s population reaches 10.4 billion, while in the WC’s projection, the world’s population tops out at 8.9 billion.

The difference in the projections comes down to assumptions about how quickly Africa’s fertility rate—or the average number of children that a woman has in her lifetime— drops from the current level of more than four to just over two, which is the point at which the population stops growing.

The speed of the decline will depend on factors like education and career opportunities for women.

If Africa’s population peaks earlier than expected, then the world’s population will also peak, never reaching 10 billion. And even if it does cross that threshold, it probably won’t go much higher than that, according to most demographic models.

In the meantime, Africa’s population is going to grow rapidly—something that is a burden for the continent in the short-term, but an opportunity longer term.

That’s because after a country goes through its population boom, it later receives an economic benefit.

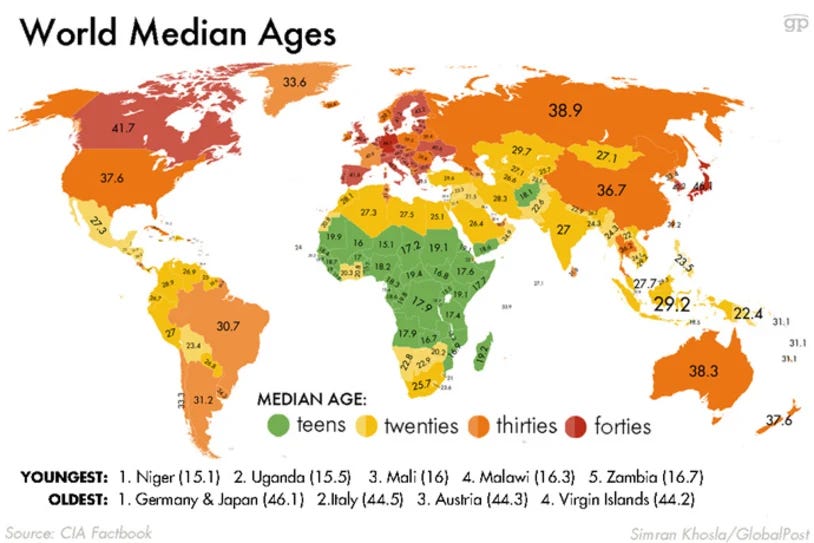

Today, because of high birth rates and a rapidly growing population, Africa has a large number of really young people. For example, the median age in Niger is 15, which compares to a median age of 46 for Japan.

Initially, having a large number of young people, especially children, is a drag on the economy because they use a country’s resources but they don’t “contribute” anything by working.

But as the population ages and those children become working adults, that reverses.

Suddenly, you have a large number of productive, working age people contributing to the economy.

The resources previously dedicated to supporting a large number of children can be redirected to enhance investments in education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

This is called the demographic dividend, and it’s what Africa is on the cusp of reaping and what other relatively youthful countries in Asia like India and the Philippines are currently benefiting from.

But to take full advantage of the demographic dividend, a country needs to have effective policies and investments in place so that the burgeoning workforce can get to work and be productive.

Without that, the dividend could go to waste.

The Demographic Burden

The demographic dividend is available for several decades. But eventually, a country’s population growth reaches zero.

At the same time, a country’s population ages and you reach a point where there are a lot of elderly people around.

This is what developed countries are facing today and it’s essentially the opposite of the demographic dividend.

In these countries, there is an increasing number of nonworking older people compared to the working age population.

This puts strains on the economy as there are fewer people in the workforce to meet the demands of a growing elderly population which requires more and more resources to support its needs (another way to think about it is there is less tax revenue to fund social programs).

Eventually, every country is going to face this issue as the share of the global population aged 65 years or above is projected to rise from 10% in 2022 to 16% in 2050 and 24% in the year 2100.

To address this, countries will need to come up with ways to support their aging populations— either with investments in things like health care and technology— or by increasing the working-age population through immigration policies, etc.

This is going to be a big issue in the coming decades. We’ll see what happens.