The Last Fed Rate Hike

Next week's Fed rate hike could be the last one of the cycle.

Next week’s Fed meeting is a big deal because the U.S. central bank is going to make what will probably be the last interest rate hike of this cycle.

On Wednesday, May 3rd, the Fed is expected to raise the federal funds rate by a quarter of a percentage point, bringing it up to a range of 5% to 5.25%.

That’s a key level because after the Fed’s last meeting in March, it released something called the Summary of Economic Projections. And in those projections, it indicated that the fed funds rate would end the year at 5.1%, smack dab in the middle of where the Fed will probably set the rate next week.

Based on that, the assumption is that the Fed’s rate hike next week will be its last.

That’s a big deal because the central bank has been hiking interest rates continuously for a year straight.

It’s hard to remember now but the fed funds rate was zero as recently as March of last year. So after next week’s rate hike, it will have gone from zero up to more than 5% in less than 14 months.

That is an incredibly rapid pace of monetary policy tightening, the likes of which we haven’t seen in decades.

Of course, this all started because inflation got too high. These rate hikes were designed to slow demand in the economy and bring inflation down with it.

Have they worked? Well, sort of.

Year-over-year growth in the consumer price index fell from 9.1% in the middle of last year to 5% in March, while the core PCE—the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation—has fallen from 5.4% to 4.6%. But that still leaves inflation well above the Fed’s 2% target.

The Fed’s thinking is that it’s managed to bring inflation down enough where it can now sit back and watch its rate hikes work their way through the economy.

Usually, there’s a lag between when the Fed hikes rates and when the impact of those rate hikes is felt in the economy—so the Fed is counting on those lagged effects to do the rest of the work in bringing inflation down further.

But therein lies the risk. If inflation doesn’t come down as the Fed envisions that it will, or worse— it reaccelerates—then the Fed might have to start hiking rates again and at that point, it’s going to be much more difficult to bring inflation down without seeing some very negative effects on the economy.

That’s the uncertainty that exists today. Has the Fed done enough to bring inflation down to a level that it finds acceptable, like 2% or 3%?

We’ll find out in the coming months.

But in the meantime, people are probably going to breathe a sigh of relief that, at least so far, the Fed’s extremely rapid interest rate hikes haven’t broken anything too badly in the economy.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and a few other regional banks was the worst thing we’ve seen thus far (and the pullback in regional bank lending could actually help bring inflation down).

But the U.S. economy as a whole has done pretty well, and it’s dodged the recession that so many people have been calling for.

The economy continues to grow.

And unemployment remains near multidecade lows.

You never know what’s going to happen in the future—we could still get a recession this year or next year; you can’t rule anything out. But you have to admit that the U.S. economy has been extremely resilient over the past year in the face of absolutely massive rate hikes.

Ironically, some of that resiliency can be attributed to the factors that contributed to high inflation in the first place, like the stimulus payments and ultra-low interest rates that we saw during the pandemic.

People are sitting on a big pile of savings that they accumulated during the pandemic, so they’ve been able to continue spending despite high inflation.

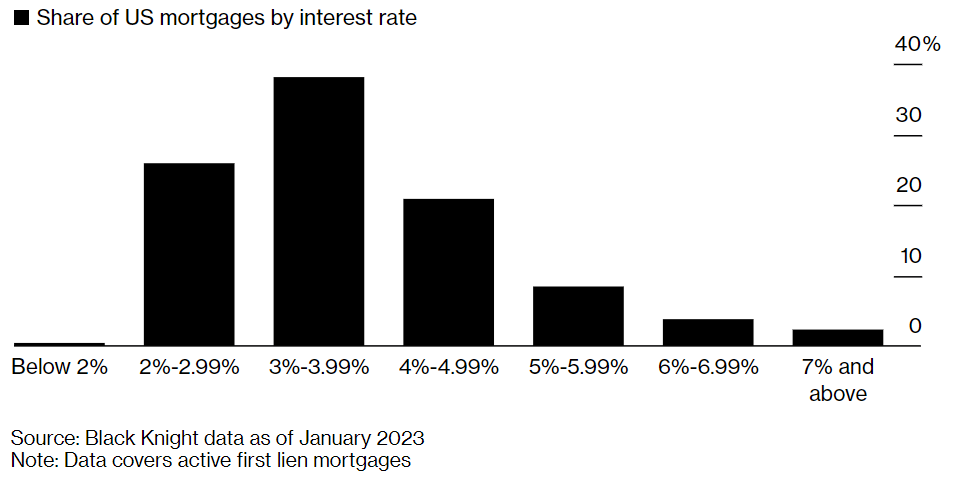

Meanwhile, many homeowners are locked into super low mortgage rates, so their payments haven’t gone up even as rates have surged. Many companies borrowed money at very low interest rates as well.

In other words, a lot of people and firms have been insulated from the full effects of the Fed’s rate hikes.

But as time goes on, savings surplus will dwindle, making peoples’ finances a little bit tighter; and homeowners and companies who borrow money going forward, will have to pay much higher interest rates than would have been the case a year ago.

Those are examples of the lagged effect of rate hikes that I talked about earlier.

But despite all of that, like I said, the economy is holding in there and the Fed pausing rate hikes is generally good news for the economy, as well as the stock market.

Based on the past six rate hiking cycles, U.S. stocks have risen an average of 19% in the year after the last Fed rate hike.

Don’t take that as gospel. It doesn’t mean the market is definitely going to rally this time around, but it is an encouraging data point.