The NOPEC Bill

If push came to shove and a U.S. president wanted to retaliate against OPEC, there is one bazooka that they could use.

This is going to make some American politicians upset.

Today, OPEC made the surprise decision to cut its oil production by 1.2 million barrels per day, which is a complete reversal from what Saudi Arabia’s energy minister said only weeks ago.

“The agreement that we struck in October is here to stay for the rest of the year, period,” Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman said on Feb. 14.

The prince was referring to the agreement that the group known as OPEC+ made in October to cut oil production by 2 million barrels per day.

That decision sparked outrage among U.S. politicians, who accused Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and other major oil producing countries of supporting Russia in its war against Ukraine.

“There’s going to be some consequences for what they’ve done with Russia,” President Biden said at the time.

Biden was upset that OPEC had agreed to cut oil production at a time in which the U.S. and its allies were facing record-high energy prices and when they were trying to choke Russia off from money that it could use to fund its war against Ukraine.

Russia is one of the two largest oil exporters in the world along with Saudi Arabia. It relies on oil and gas sales to fund nearly half of its federal budget.

Historically, Russia hasn’t been a member of OPEC, but it started to coordinate with the group in 2016. When Russia acts in concert with OPEC, people refer to the broader group as OPEC+.

To U.S. politicians, when OPEC+ decided to cut oil production by 2 million barrels per day in October, it looked like Saudi Arabia and other OPEC members were helping Russia and working against the U.S. and its interests in Ukraine.

They were trying to prop up oil prices, which directly benefits Russia.

But that decision, as well as today’s decision to cut production by another million barrels per day, might not be as nefarious as they seem. After all, OPEC has been making decisions to adjust its oil production for decades.

That’s the whole point of the organization. It’s what economists call a cartel (a group of businesses or nations that work together to increase profits).

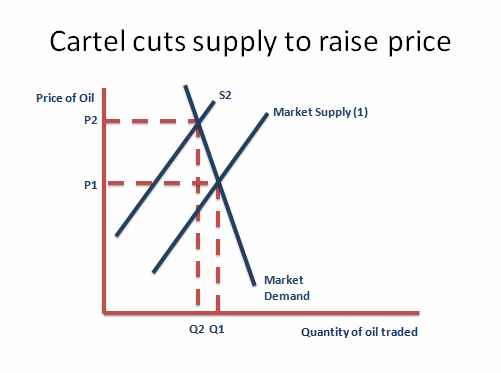

In theory, by working together, members of OPEC can reduce their oil supply by a certain percentage, leading to an even bigger percentage increase in the price of oil. As a result, they make more money than if they didn’t work together to limit supply.

In theory, this sounds like a good idea, but in reality, OPEC hasn’t been an effective cartel because its members end up cheating on each other.

Members say that they’ll cut their supply by a certain amount, but they don’t follow through and do it. They secretly pump every barrel of oil that they can and hope that all the other members cut back on their supply.

Since there’s no way for the cartel to enforce its quotas, there are no consequences for the cheating and in the end, almost every member ends up selling every barrel of oil it can.

The only members who seem to consistently follow through on their pledges is Saudi Arabia—which makes sense since it has the most to gain or lose from changes in oil prices—and its neighbor, the UAE.

According to a 2021 study, OPEC members have historically cheated on their commitments 96% of the time!

In fact, since OPEC+ member countries said that they would cut their oil production by a collective 2 million barrels per day in October, their actual production has fallen by only 500,000 barrels per day—most of which was the result of declines from, yes, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

At the same time, since the date of that announced October production cut, oil prices have fallen from $93 to less than $80.

This is the perfect illustration of the fact that OPEC isn’t a very effective cartel.

But even so, the fact that OPEC is coordinating with Russia at a time in which Russia is on really bad terms with the U.S., adds an element of political sensitivity to OPEC’s decisions, even though these decisions have quietly been made for years without incident.

Additionally, the recent strain in the relationship between the U.S. and OPEC's top oil producer, Saudi Arabia, has further intensified the scrutiny of these decisions.

Personally, outside of the rare cases when oil prices are really high or really low, I don’t believe that OPEC’s decisions are all that consequential. Oil prices today are around $80/barrel—which is in the ballpark of where they were five years ago, 10 years ago and 15 years ago.

And if you look at the price of oil on an inflation-adjusted basis, it’s right around its 40-year average.

Based on the evidence, OPEC just isn’t a huge factor in driving long term oil prices.

But, as I’ve been saying, the shifting geopolitical picture has colored how the U.S. views OPEC’s actions, and for better or for worse, at some point, we could see retaliation by the U.S.

Remember, President Biden threatened consequences for OPEC in October.

So far, we haven’t seen him actually do anything. But if push came to shove and Biden or another U.S. president wanted to retaliate against OPEC, there is one bazooka that they could use.

It’s called NOPEC (No Oil Producing and Exporting Cartels Act), a bill that would open OPEC member countries up to lawsuits for violating U.S. antitrust laws.

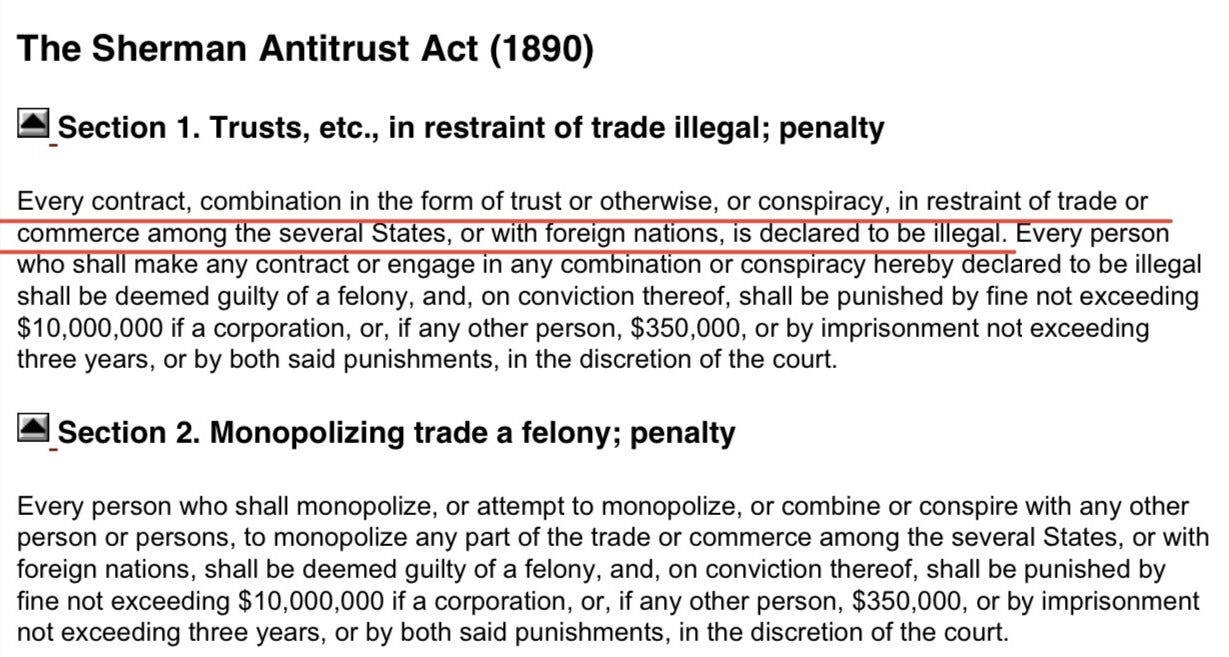

Remember how I mentioned how OPEC is a cartel earlier? Well, cartels are illegal in most countries.

In the U.S., the Sherman Antitrust Act prohibits anticompetitive practices that attempt to restrain trade and commerce—something that OPEC clearly tries to do by limiting oil production.

But currently, OPEC member countries have sovereign immunity from U.S. lawsuits, which means they cannot be sued in U.S. courts.

The NOPEC bill would remove that immunity, opening OPEC countries up to lawsuits from the Department of Justice.

Proponents of the NOPEC bill argue that OPEC shouldn’t be allowed to collude and attempt to restrict oil supply and raise oil prices.

They believe that the threat of lawsuits would lead to increased oil supply, as the OPEC countries that are restricting their oil production—primarily Saudi Arabia and the UAE—would be compelled to release all of their oil onto the market.

But there are many opponents to the NOPEC bill as well.

As OPEC itself argues, the NOPEC bill could cause more volatility in oil prices by reducing the ability of OPEC countries to smooth out oil price fluctuations by increasing production when prices and high and decreasing production when prices are low.

Others believe that the bill would severely damage diplomatic relations between the U.S. and OPEC oil producing countries, potentially leading to economic blowback on America.

With the threat of lawsuits hanging over them, oil producing nations could reduce their investments in American assets, fearing that those assets could be seized as part of any legal judgments against them.

American company’s overseas assets could also be put at risk from retaliation by OPEC members. And America’s geopolitical interests in the Middle East and Africa, where many OPEC countries reside, could be hurt by the passing of this bill.

As the Baker Institute points out, for many of these oil producing countries, oil is an “existential economic priority and in some cases, underpins the survival of ruling families,” while for the U.S., it’s “only one of many competing priorities.”

In other words, the NOPEC bill could introduce a lot of problems for the U.S. in exchange for very little upside.

That’s probably why the NOPEC bill has never been signed into law despite being introduced to Congress so many times. The closest it got was in 2007, when the bill easily passed both chambers of Congress, but failed to become law after President George W Bush threatened to veto it.

You never know what could happen, but I find it unlikely that the NOPEC bill is going to pass this year if it didn’t pass last year, when oil prices were much higher and when the Russia-Ukraine war was more of a front page story than it is today.

It feels like a bill like this has the greatest chance of passing when oil prices are really high and politicians are looking for someone to blame for those high prices.

That’s not the case today, but one day we could get the perfect storm that pushes an American president to support this bill and sign it into law.