Why I Bought Chevron Stock

A pair of big oil companies are in flux as Venezuela threatens Guyana.

If Venezuela invades Guyana, arguably no company will be hurt more than Hess. The American oil company has a 30% stake in the Stabroek Block, a 6.6-million-acre oil-rich area off the coast of Guyana.

Hess bought its interest in Stabroek from Shell back in 2014 for just $1 (that’s not a typo). For five decades, Shell failed to find much oil in Guyana, which caused the company to throw in the towel and exit the country.

But it turns out that Shell’s timing couldn’t have been worse. Just a year later, in 2015, ExxonMobil, together with its new partners, Hess and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), discovered enormous amounts of oil in the Stabroek Block.

Today, it’s believed that there are more than 11 billion barrels of recoverable oil in the area, worth three-quarters of a trillion dollars at current oil prices.

By the end of 2027, it’s estimated that 1.2 million barrels of highly profitable oil could be pumped from Stabroek every day, catapulting Guyana into the top 20 oil producing countries in the world.

Even for a giant like Exxon, that’s a big deal. Exxon’s 45% stake in the project translates into more than half a million barrels per day of oil production in 2028—or just under a fifth of the company’s projected oil production for that year.

But for Hess? It’s an even bigger deal. By 2028, Guyana could represent almost three-quarters of Hess’s total oil production, helping the company to generate $4 billion in profits per year.

The Guyanese oil is so lucrative that Chevron agreed to purchase Hess several weeks ago for over $50 billion.

But all of this could be at risk if Venezuela follows through on its promise to take over Essequibo, a 62,000 square mile territory that’s controlled by Guyana today and makes up two-thirds of the land area of the country.

For around 200 years, Venezuela has claimed that it rightfully owns the Essequibo territory, not Guyana. The reasons for the dispute are beyond the scope of this post (it goes all the way back to the British and Spanish colonial days).

Suffice to say, every several years, this dispute flairs up, but nothing really changes. The two countries agreed in 1966 to settle the matter peacefully and it’s currently being adjudicated in the International Court of Justice.

But Venezuela might not be interested in a peaceful settlement.

After huge amounts of oil were discovered off the coast of Essequibo in 2015, Venezuela has grown more emphatic in its claims that Essequibo belongs to it.

A week ago, the Venezuelan government held a referendum asking Venezuelans whether they agreed with the creation of a Venezuelan state in the Essequibo region, and whether to grant citizenship to the region’s current residents.

The referendum overwhelmingly passed, which prompted Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro to order his country’s state-run oil companies to immediately begin developing Essequibo’s oil resources—a move which some people saw as a potential precursor to more forceful action to bring Essequibo under Venezuelan control.

Investors in Hess took notice of that. Since the referendum, shares of the company have fallen by 5%. They are now trading at a 10% discount to Chevron’s acquisition price.

You could consider this discount an indicator of the likelihood of a Venezuelan invasion of Guyana in the next seven months—which is the timeframe within which Chevron’s buyout of Hess is expected to close.

If investors think an invasion is more likely, the discount should increase; if they think it’s less likely, the discount should decrease.

The idea is that if Venezuela did go to war with Guyana, that would be considered a “material adverse event” and Chevron would abandon its acquisition of Hess.

Granted, Hess’s discount might not only be due to the risks of a Venezuelan invasion of Guyana. Some of it may have to do with the Federal Trade Commission recently opening an investigation into Chevron’s buyout of the company.

If the FTC thinks the merger is anticompetitive, it could sue to stop it from happening.

The regulator also opened a similar investigation into the other big oil acquisition of this year—Exxon’s $60 billion buyout of Pioneer Natural Resources.

But while Pioneer’s discount to its acquisition price widened after the FTC probe came to light, its discount is still only 4% today, which is less than half of the 10% discount on Hess.

That’s likely a reflection of the fact that Pioneer isn’t impacted by the same geopolitical risks as Hess, since it only produces oil in the United States.

So, what should we make of all this? Well, to me, these numbers suggests that investors believe that there is a growing risk that Venezuela invades Guyana.

A couple of weeks ago, Hess was trading at a 2% discount to its acquisition price; now it’s trading at a 10% discount because of all the noise the Venezuelan government has been making about taking over Essequibo.

But while investors are getting nervous, they aren’t panicking. If they were convinced that an invasion was imminent, I think we’d see a much larger discount on shares of Hess since the oil assets in Guyana are so integral to the value of the company.

How Likely Is An Invasion?

I’m not a military or geography expert, but from what I’ve read, an invasion of Essequibo by Venezuela would be exceptionally challenging. The region is largely made up of rugged, impassable rainforest that would be extremely difficult for any army to traverse.

Venezuela’s economy is also in shambles, so any costly military adventure would be difficult to fund or justify.

Additionally, Brazil, which lies between parts of Venezuela and Guyana, has warned that it doesn’t want to see a war, while the U.S. recently performed military drills with Guyana to discourage Venezuela from making any hostile moves.

On the other hand, if Venezuela does decide to go head-to-head with Guyana, it would have an obvious military advantage thanks to the size of its population. 28 million people live in the country, 35x as many as who live in Guyana.

Bluffing

Most people believe that Venezuelan President Maduro is making so much noise about Essequibo right now to gin up support for his administration ahead of elections next year, and that he doesn’t really intend to take military action against Guyana.

After all, it was only a couple months ago months ago, that his government made a deal with the U.S. to release political prisoners and hold fair elections in 2024 in exchange for the easing of sanctions on Venezuelan oil.

It would be counterproductive for him to turn around and do something that would cause the U.S. to reimplement those sanctions or take even more aggressive measures against Venezuela.

So, let’s hope there is no invasion. It would be bad for the people of Guyana and their economy, which is the fastest growing economy in the world. If current projections for the country’s oil production are accurate, Guyana’s GDP per capita could grow to $36,000 by 2027, up sixfold from 2017.

But you never know what will happen. After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 to the surprise of pretty much everyone, you can’t really count anything completely out.

Investment Perspective

From an investment perspective, I think that this is an interesting opportunity. If the consensus is right and Venezuela doesn’t invade Guyana—or at least, doesn’t invade Guyana in the next seven months—then Chevron’s acquisition of Hess should close at the agreed upon price (it’s unlikely that the FTC will be able to block the buyout).

The classic way to bet on the merger closing is to short shares of Chevron and buy shares of Hess, thereby capturing the 10% spread between where Hess is trading at today and the full price that Chevron is paying for the company.

The risk to that arbitrage is that the spread could continue to widen if tensions between Venezuela and Guyana intensify, or worse, Venezuela actually invades its neighbor, causing Chevron to call off the merger and Hess’s stock to plunge.

Another option is to buy the stock of Hess outright. The benefit of this approach is you don’t have to deal with shorting stocks, which a lot of investors don’t like to do.

You also have the potential for additional upside beyond 10% if the merger closes and shares of Chevron go up from here (Chevron has agreed to pay investors in Hess 1.025 shares of its stock for every share of Hess, so shares of Hess are linked to shares of Chevron).

However, this exposes investors to the same risks as the first approach. If Venezuela invades Guyana, shares of Hess could drop significantly.

Personally, the 10% discount that Hess is currently trading at isn’t compelling enough for me to buy it. I figure, if Venezuela really does invade Guyana, we could see a 30% to 50% drop in the stock.

I don’t want exposure to that risk, no matter how remote it is, especially for just 10% upside. Maybe if the discount widens to a much higher level, like 20% or more, I might take a look at buying Hess, depending on the circumstances.

But that’s just me. You might believe that the risks of Venezuela invading Guyana are so low that it makes sense to buy Hess for a 10% or greater gain over the next several months.

The approach I took is a little bit different. A few days ago, I bought a small position in Chevron. Shares of the oil company fell about 15% due to its acquisition of Hess, and they’re currently trading near their lows for the year.

As long as oil prices don’t decline significantly from here, I think the stock could recoup most of those losses.

With Chevron, I don’t have to worry about geopolitical risks surrounding Venezuela and Guyana, at least until the buyout of Hess closes.

I’m not a bull on oil long-term since the world is inexorably transitioning away from fossil fuels. But oil is going to stick around for many more years and the companies that produce it are going to continue to make money for now.

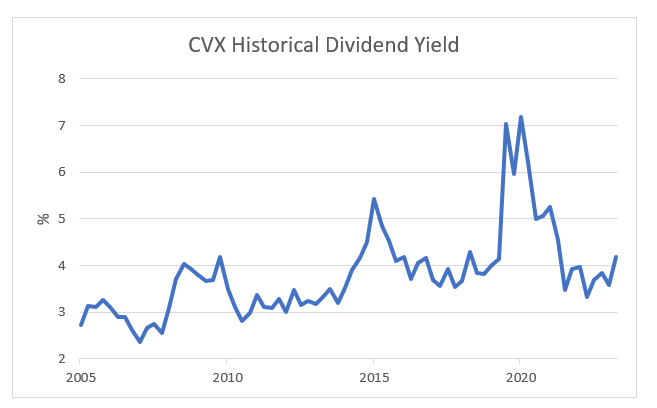

Chevron currently pays a 4.2% dividend, which has generally been an attractive yield on the stock.

I’ll probably sell it after a 10% to 20% bounce—so this isn’t a long-term buy and hold investment for me; it’s a trade.

Thanks for reading!