Why The Music Industry Is Embracing Crypto

There's much more to crypto than scams and speculation.

I just bought streaming rights for a hit Justin Bieber song for $25.

I’m going to tell you how and why I did it, but this is about a much bigger topic—which is how a certain new technology could transform the music business, and how that same technology could revolutionize many other parts of our economy as well.

So, let’s get into it.

You see, the music industry has been on a rollercoaster ride. For much of the history of recorded music, the sale of physical copies of music was the way in which artists made money from their craft.

And though the format of those physical copies of music has changed over time—from vinyl records to cassette tapes to compact discs—for many decades, sales were going up and things were good for the industry.

But that came to a screeching halt around the turn of the century. What happened then?

Well, as you probably know, the internet took off. All of a sudden, consumers weren’t interested in buying CDs anymore; they were more interested in downloading pirated music off the internet using file sharing services like Napster, Kazaa and LimeWire.

For a long time, the music industry tried to fight this. It filed lawsuits against file sharing services and even individual users of those services—ordinary people like you and me.

But it was a lost cause. Every time one file sharing service shut down, another one popped up in its place. And music fans continued to share and download mp3 files even in the face of legal threats from the music industry.

For the next decade and a half, revenues from the sale of recorded music plunged, from a high of $14.6 billion in 1999 to $6.7 billion in 2015.

The Turnaround

Things looked hopeless for the music industry. The lawsuits weren’t working, and an attempt to sell digital music files to consumers directly through iTunes and other digital media stores wasn’t enough to offset the lost revenue from piracy.

But then around the middle of the 2010s, something changed.

Streaming services, like those offered by Spotify and Apple Music, started to take off. All of a sudden, for a flat monthly fee, you could get access to all of your favorite songs using a sleek user interface.

There was no need to mess around with clunky file sharing services and risk getting your computer infected with a virus. Pirating music just didn’t make sense anymore.

So, streaming killed widescale music piracy, and it also transformed the business model of the music industry from one focused on the sale of physical copies of music to one focused on subscriptions, helping to bring the industry back from the brink.

In 2021, thanks to streaming, recorded music revenues finally surpassed their 1999 peak (though on an inflation-adjusted basis, they’re still below that peak). Today, over two-thirds of the revenue from recorded music comes from streaming.

So, that’s good news: revenues for recorded music are growing again. But it’s not all rosy.

Yes, streaming has done a lot to compensate artists for their work. And streaming, along with social media, has done a lot to give smaller artists a chance to succeed and make a living creating music.

For instance, over nine million people have uploaded music to Spotify, including more than three million people who have uploaded at least ten songs onto the platform.

But just like in the era of physical music, it’s still the case that most of the attention and money flows to the top artists.

In 2022, only 213,000 artists on Spotify had released ten songs or more and attracted at least 10,000 monthly listeners. An even smaller number of people—57,000—generated royalties of $10,000 or more that year.

In other words, millions of people have uploaded music to Spotify, but only a small percentage of those are making a decent amount of money off of those songs.

Even concerts, which is a source of revenue that many artists use to supplement the money they get from recorded music, is top heavy, with 1% of performers taking 60% of all concert ticket sales.

So, if you’re successful enough to be a top artist, sure, you can make a living creating music. But most artists can’t.

Which raises the question: how might this change? What can be done to give more artists a shot at success?

Well, to answer that question, let’s go back to what I talked about earlier— how I bought streaming rights for a Justin Bieber song for $25.

The song is called “Company” and it was released back in 2015. It has over 500 million streams on Spotify and almost 700 million views on YouTube.

I bought streaming rights to the song off a marketplace called anotherblock ¹, which is a platform that sells music non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

Now, I know a lot of people roll their eyes when their hear about NFTs or anything to do with crypto—and understandably so. The industry is filled with scams and grifters.

But this is a case where the primary technology underlying crypto— the blockchain—can add a lot of value.

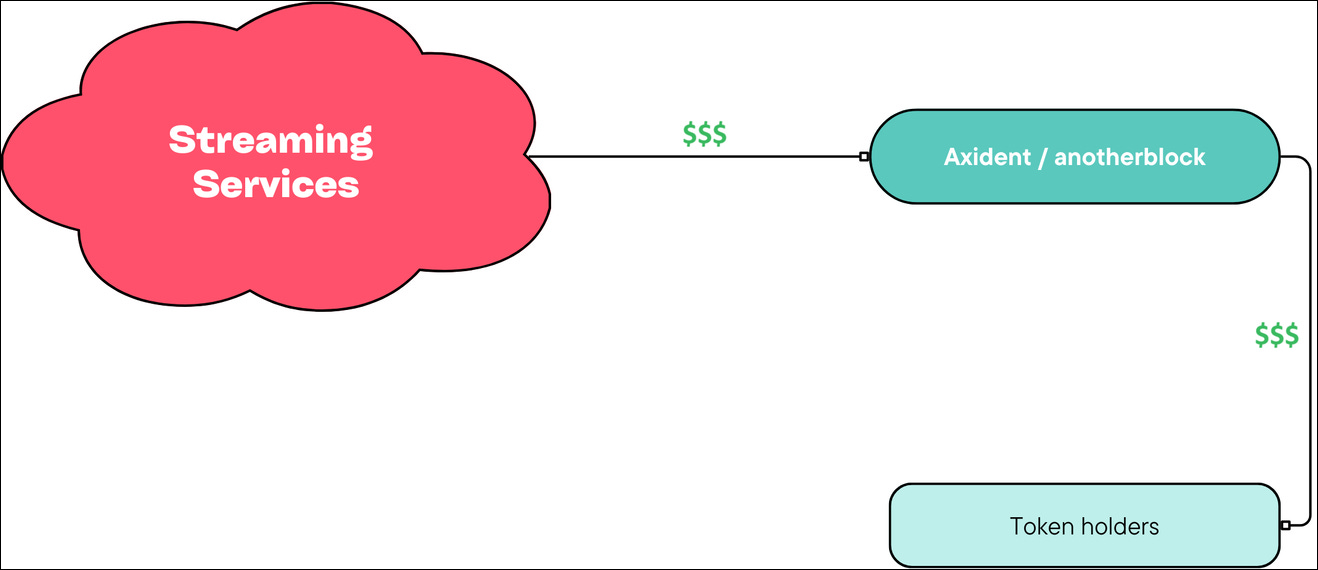

You see, what I bought on anotherblock is an NFT that represents rights to a share of the future streaming revenue from “Company.” Specifically, the one token I bought represents 0.0005% ownership of the song’s streaming rights.

I know that sounds small, but it’s still pretty cool. By buying this token, I’m essentially a partial owner of the song—which is something I could never have been in the past.

To be clear, Justin Bieber wasn’t directly involved with these NFTs (though he has dabbled with other NFTs in the past).

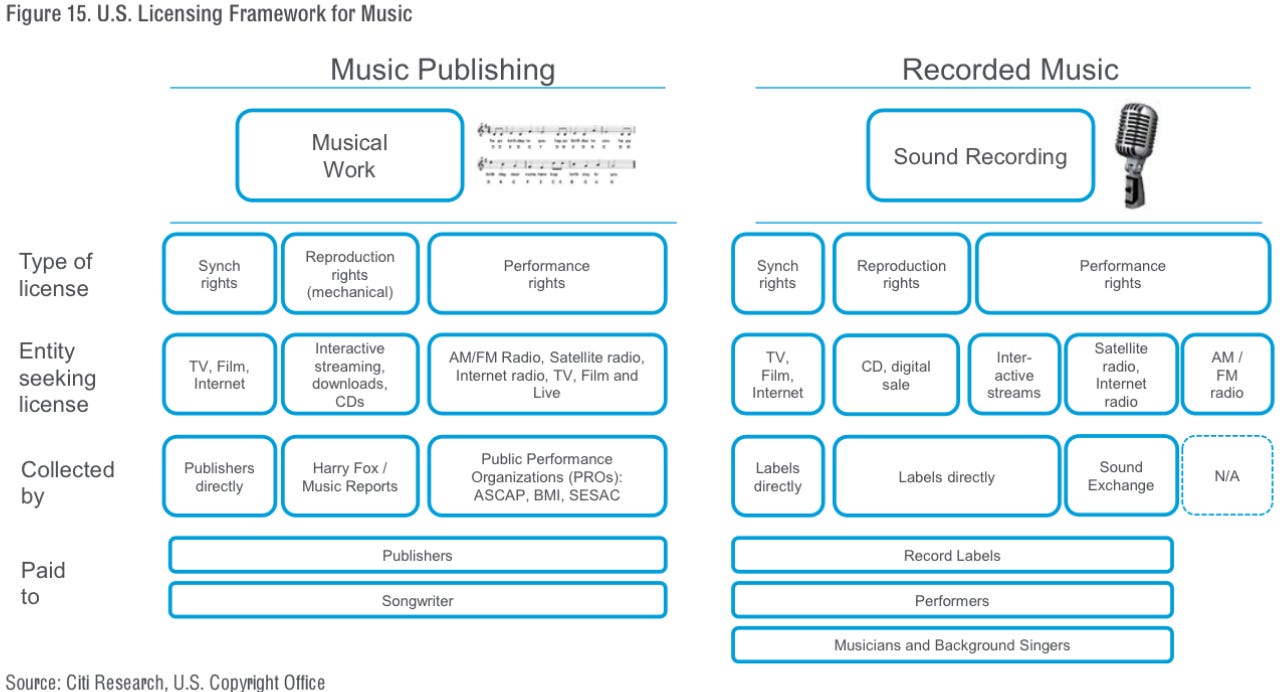

Music streaming rights are extremely complex, and everyone including musicians, songwriters, record labels, publishers and a host of other parties often hold rights to the royalties generated from a song.

In this case, one of those rights holders—Axident, who helped produce the song— decided to sell the future revenue associated with his rights in the form of crypto tokens.

There were 2,000 tokens sold, and like I said, each one represents 0.0005% of streaming rights, which means all the tokens combined have rights to 1% of the song’s streaming revenue.

So, whenever streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music pay royalties for the song, some of that goes to anotherblock, who passes it on to token holders like me ².

This is cool because a lot of the criticism that’s been aimed at crypto is that it’s useless and that it’s all speculation. I’m sure you saw a couple years ago how tokens associated with pictures of apes were selling for millions of dollars.

Well, this is different. You have real cash flows associated with music streams flowing to holders of music NFTs.

Additional Benefits

“Company” isn’t the only song whose streaming rights have been turned into tokens. Royal, another platform focused on music NFTs, has sold tokens tied to songs from Nas, The Chainsmokers, Diplo, and many other artists—both big and small.

The neat part about the tokens sold by Royal is that they sometimes offer a lot more than just the revenue associated with music streaming rights. Some artists give token holders additional benefits, like merch, concert tickets, private listening parties, and meet & greet opportunities.

So, this is a new way for artists to connect with their biggest fans directly. I’ve talked a lot about well-known artists like Justin Bieber and The Chainsmokers, but especially for smaller artists, the ability to raise money directly from fans, and then have fans be co-owners of their work, is huge.

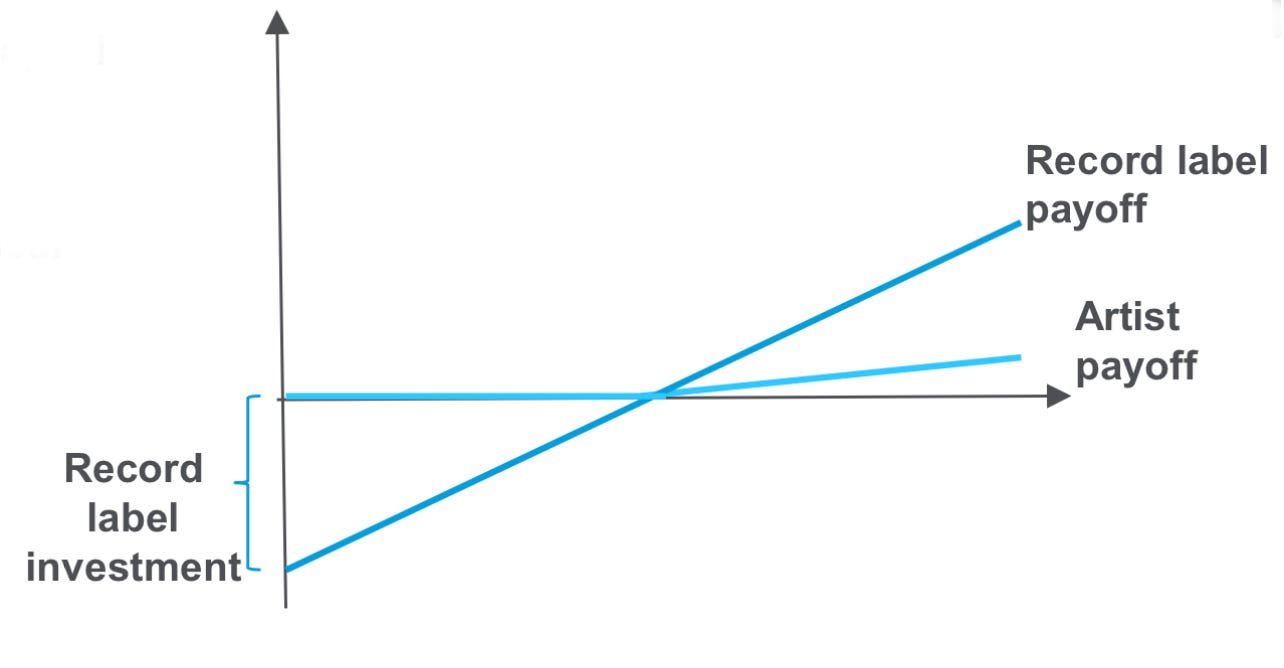

It takes some of the power away from record labels and puts it into the hands of artists, who have a new way to fund themselves without having to give up a ton of upside to big companies.

At the same time, it makes music royalties easier to buy, sell, and price, making them more valuable— both for the artists who sell them, as well as those who buy them (including buyers who are fans and buyers who aren’t necessarily fans but want to invest in an artist and potentially profit from their success).

So, I’m excited to see how music NFTs evolve ³.

But this isn’t just about music. Blockchain—which, again, is the primarily technology underlying crypto—can revolutionize many parts of our economy.

It’s a completely new type of computing system that’s operated not by one entity like a person, a company or a government, but by an entire network of participants. And this decentralized design gives it features that you don’t get with more centralized systems.

Anyone, for instance, can use Ethereum, the world’s most popular general purpose blockchain, to create and engage with what are known as “smart contracts,” which are computer programs that run automatically as people interact with them.

These smart contracts also store data permanently— and that’s what makes blockchains so revolutionary. Data is stored forever in a computing system that’s open to everyone and operated collectively by many different participants.

This creates a level of trust in blockchains that you might not have in more centralized systems, where one entity can single handedly change things.

We’ve all heard of situations where people have gotten kicked off certain platforms—whether rightly or wrongly—for the things that they’ve said or done. Worse, in some countries, governments have confiscated peoples’ assets without due process. That’s the type of risk that blockchains could potentially reduce significantly.

Given the characteristics I just talked about, blockchains are the perfect place to track the ownership of assets—assets that can be represented as tokens in the blockchain database.

You can use smart contracts to create tokens to represent anything. That includes purely digital assets—like cryptocurrencies and items in video games— or real-world assets—like music streaming rights, physical property, and traditional (fiat) currencies.

These tokens can’t just be stripped away by the arbitrary whims of a company or a government ⁴, so people have confidence that they will continue to own them as long as they want to. That’s why a lot of people consider blockchains to be property rights systems.

Another great thing about tokenized assets is they benefit from the unique properties that blockchains enable, like interoperability and composability.

For example, I could take a music NFT that I purchased on Royal and put it up for sale on another marketplace like OpenSea. Or I could use the NFT as ticket to get into an in-person or online event. I could also use it as collateral for a loan from a blockchain-based lending application.

Any app could potentially see that I own this music NFT and be able to interact with it and me in interesting ways.

The possibilities are endless and only with time will we see what completely novel types of experiences are created on the back of blockchains.

With that said, even though blockchains holds a lot of promise, they are not the solution for everything. In many cases, a more centralized system works just as well or better than a blockchain.

If the priority is speed, cost efficiency, and control, then a blockchain might not make sense.

Even when it comes to music royalties, there are more traditional competitors to NFT platforms like Royal and anotherblock that work just fine. The big one is RoyaltyExchange, which has been facilitating the sale of music royalty revenues for over a decade.

I’ve never used it myself, but they have an extensive catalogue of music royalties available on their marketplace.

There are no crypto tokens involved, so you don’t get those benefits of the blockchain that I discussed earlier, but that might not matter to you.

You can still use their marketplace to buy and sell royalty rights; you just can’t easily transfer those rights off of the platform or use them for anything else like you could if those rights were in the form tokens on the blockchain ⁵.

So, we’ll see what happens. As time goes on, I do think we’re going to see the ownership records of an increasing number of assets—both physical and digital—on the blockchain. But there’s still a lot of work that has to be done before this technology can really become mainstream.

¹ The NFTs were first sold on anotherblock. I used the marketplace, OpenSea, to buy them off someone who wanted to resell them.

² These particular NFTs tied to “Company” don’t offer royalties to U.S. citizens due to “regulatory uncertainty.” This is probably because of the SEC’s war against crypto. However, there are many other music NFTs that do pay royalties to Americans.

³ I bought $25 of music NFTs as an experiment. I don’t intend to put a significant money into these tokens anytime soon. Anyone who purchases similar tokens should know that they are extremely high risk, with the potential for steep price declines.

⁴ The tokens themselves can’t be stripped away, but if the tokens represent ownership of “real world” assets, that ownership is dependent on real world institutions, like the legal system. For instance, music NFTs rely on a contract between the token holder and the original music royalty rightsholder (or the platform that facilitates the sale of the tokens). That contract stipulates that the token holder is entitled to a portion of the royalties from the song in question. The blockchain can’t enforce this contract; only the real-world legal system can. However, the blockchain can store information about the contract.

⁵ RoyaltyExchange started offering music NFTs in 2021, but it’s not active in the space.