The Great Interest Rate Debate

Are high interest rates here to stay?

This might be the most important question when it comes to the future of our economy, yet no one knows the answer to it:

Are high interest rates here to stay?

If you’ve been keeping up with the financial media recently, you’ve probably seen all of the shock and angst caused by what’s going on in the U.S. Treasury market.

This month, the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note—which is arguably is the most important interest rate in the economy—surged to a 16-year high close to 5%.

This is different than the rate hikes by the Federal Reserve we’ve been hearing about over the past year and a half.

This is a much bigger deal because it suggests that financial markets may be starting to anticipate a world in which interest rates are going to be significantly higher going forward than they were over the past decade and a half.

If that’s the case, then the entire economy may need to adjust to this new paradigm, and that could have dramatic consequences for consumers, businesses, governments, stock prices, house prices— and more.

I’m going to talk about what this might mean for the economy, but before I do, let’s quickly go over how we got to this point, so you have more context for what I’m going to discuss later.

How We Got Here

Let’s start by rewinding the clock back to March 16, 2022. That’s the date on which the Fed hiked a key interest rate for the first time in over three years in response to skyrocketing inflation.

As you might know, the Fed conducts monetary policy by adjusting the federal funds rate, which is the rate that banks pay to borrow money from each other overnight.

The Fed uses the fed funds rate as a tool to either slow down or speed up the economy. In this case, the central bank was trying to slow down the economy in an attempt to bring inflation down with it.

In the year and a half following that first rate hike, the Fed continued to lift the fed funds rate—from an annual rate of zero in March of 2022 to 5.5% in July of this year—a massive increase, the likes of which we haven’t seen since the 1980s.

Fortunately, the rate hikes seemed to work. Inflation fell from a high of more than 9% in June of 2022 to around 3% to 4% today. And a lot of people expect that the inflation rate will continue to move lower from here.

As you might expect, the Fed is happy with that— but it’s still not satisfied. The central bank targets an inflation rate of 2%, and as long as inflation continues to run above that level, the Fed has promised to keep its foot on the brakes of the economy.

That said, just because the Fed says it will keep its foot on the brakes, doesn’t mean it’s going to keep hiking rates indefinitely.

In his most recent comments, Fed chair Jerome Powell said that because of the progress he and his colleagues have seen in bringing inflation down, the central bank probably doesn’t have to increase the fed funds rate much more from here—it’s already at a level that, according to Powell and the Fed, is restrictive enough to slow the economy and inflation over time.

However, he also said that just because the Fed will eventually stop hiking rates, doesn’t mean it’s going to suddenly turn around and start cutting rates.

According to Powell, after the Fed makes its final rate hike (which very well could have been in July, when the Fed raised rates to 5.5%), the central bank is going to keep the fed funds rate at or near its peak level for as long as it takes to ensure that inflation comes down to 2% and stays there.

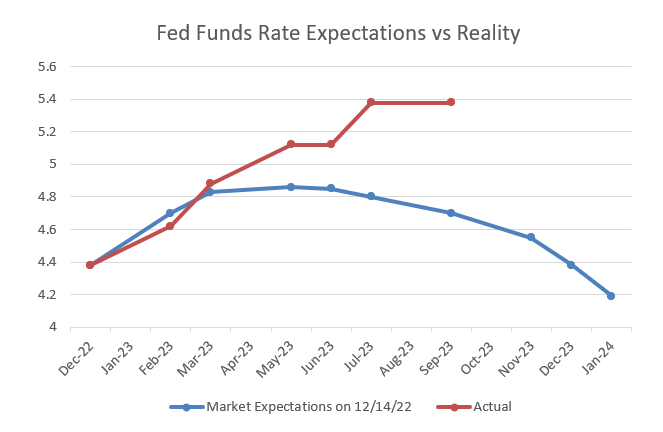

Now, these comments from Powell weren’t that surprising. Powell and other Fed officials have been saying similar things for a while.

It’s just that no one believed them.

For much of the past year and a half, most people expected that once the Fed finished hiking the fed funds rate, it would quickly reverse course and cut rates.

Their reasoning was that such a massive increase in interest rates would slow the economy dramatically, pushing it into a recession.

But that recession never materialized—not even after the shocking collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and a handful of other regional banks earlier this year.

In fact, rather than slowing down sharply, the U.S. economy seems to be holding steady or even strengthening—a confounding outcome in the face of the Fed’s massive rate hikes.

With no recession in sight, people started to throw in the towel on rate cuts and accept the Fed’s view that rates would stay high for a while.

A lot of people are calling this idea “higher for longer”— the fed funds rate is going to stay at a level higher than most people thought for longer than most people thought.

This higher for longer narrative might be a reason why rates on the all-important 10-year Treasury, as well as other longer-term bonds, spiked in recent weeks.

If the federal funds rate is going to stay above 5% for the next 12 months, 18 months, or whatever the case may be—then that is going to exert an upward gravitational pull on other, longer-term interest rates as well.

It’s actually typical for long-term interest rates to be higher than short-term interest rates, so the fact that the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury has been below the fed funds rate for nearly a year is unusual.

This phenomenon is known as an inversion, and it’s a reflection of economic concerns. People expect the economy to weaken and for the Federal Reserve to respond to that with rate cuts, so long-term rates are below short-term rates in anticipation of those Fed rate cuts.

But as I said earlier, because the economy has been so strong, the rate cut expectations are being thrown out, and the relationship between short-term and long-term interest rates is normalizing.

The interest rate on the 10-year Treasury bond today is still below the fed funds rate, but the gap has narrowed significantly as people start to believe in the “higher for longer” narrative.

But that isn’t the end of the story. “Higher for longer” is one explanation for the spike in long-term interest rates—and it almost certainly has played a part in the rate increases we’ve seen.

But there is a much more audacious view—let’s call it the view of the bond market bears— that says long term interest rates are going up, not just because of the Fed’s commitment to keep the fed funds rate high to stamp out the current bout of inflation, but for more structural reasons that will reverberate for years to come.

Under this view, factors like large government deficits, de-globalization, labor shortages and geopolitics will conspire to keep upward pressure on interest rates¹ ².

For instance, the U.S. government and many corporations have been pushing to bring more manufacturing back to the U.S. because of tensions with China and because they want to strengthen supply chain resiliency more generally.

This trend, which is sometimes called de-globalization, could put upward pressure on prices because, in many cases, it’s more expensive to manufacture things in this country.

Meanwhile, the labor market has been tightening notably over the past couple of years in part due to early retirements—mostly by baby boomers—and due to a drop in immigration and birth rates to their lowest levels in decades.

A tighter labor market gives workers more power to demand higher wages, which then get passed on to consumers through higher product prices.

Under the view of the bond market bears, de-globalization and labor market tightness will increase the long-term rate of inflation, which in turn will cause bond investors to demand higher interest rates as compensation.

Large government deficits are another factor that the bond market bears point to as a cause for higher interest rates. This year, the U.S. federal government is expected to spend $1.7 trillion more than it takes in from taxes, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

In terms of dollars, that’s the largest budget deficit outside of the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021. And even as a percentage of GDP, it’s an extremely large 5.8%.

The only other times in U.S. history where there’s been deficits of this magnitude are either during big recessions—when tax revenues declined substantially—or during world wars.

The deficit has never been this large relative to the size of the economy outside of those crisis periods (which kind of makes you wonder how big the deficit could get the next time we do have a big recession).

The CBO expects that the U.S. federal budget deficit will continue to increase over the coming decade, both on a nominal basis and as a percentage of GDP, due to increased government outlays to fund entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare, as well as interest on the national debt.

As the deficit grows, the government is going to have to borrow an increasing amount of money by selling Treasury securities, which according to the bond market bears, will only be purchased by investors if they come with higher interest rates³.

So, if the bond market bears are right—we could be in for a radical shift in interest rates compared to what we experienced over the past decade and a half.

The Low Rate Era

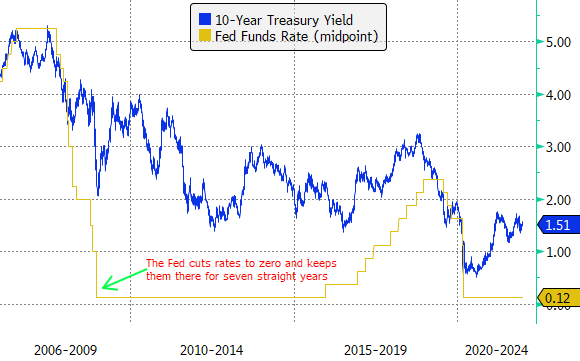

You might recall that in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2008, interest rates plunged to historically low levels and stayed there for many, many years.

The Fed kept the federal funds rate at zero for seven straight years between 2008 and 2015. Central banks around the world, like the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, did the same, and in some cases, took even more drastic action by cutting rates into negative territory.

These ultra-low interest rate policies were a reaction to the dismal state of the economy following the global financial crisis.

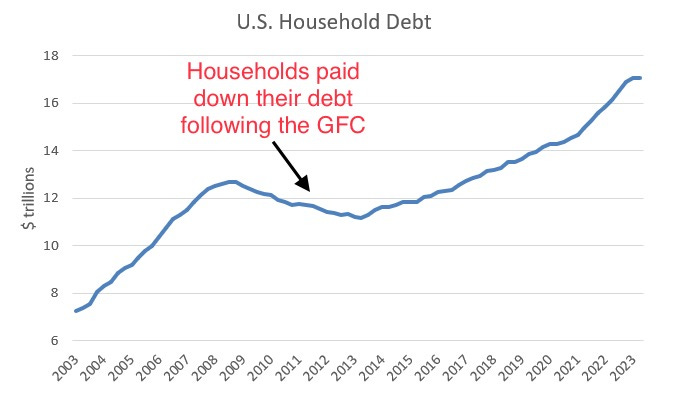

Following the GFC, economic growth was extremely weak as households, banks and other businesses worked to pay down their debts, with the scars of the crisis still fresh in their minds.

Consumers weren’t spending and businesses weren’t investing at nearly the rate they were prior to the crisis. Even the federal government became stingier about borrowing and spending money.

This lack of growth and investment pushed interest rates down⁴.

But if the bond market bears are right, then the low-interest-rate paradigm that existed in the decade and a half after the global financial crisis has ended and we’re entering a new paradigm of higher interest rates.

And not only that— if interest rates are going to be higher moving forward, then that means that the 40-year downtrend in interest rates that began in the 1980s is also over.

So, we’re talking about what could potentially be a generational shift for interest rates. Over the past 40 years, all everyone has seen is interest rates going lower and lower and lower. That could be over, according to the bond market bears.

With that said, that’s just one side of the story. There are many who still believe that nothing has fundamentally changed over the past couple of years and that rates will eventually come back down.

The people in this camp don’t believe that any of the factors I talked about before—de-globalization, tight labor markets and large government deficits—are significant enough or different enough to cause a fundamental change in what interest rates should be, and that we’re not in some type of new paradigm.

Time will tell whether the bond market bears or the bond market bulls are right about interest rates. But either way, it’s worth thinking about what higher interest rates—if they are here to stay—could mean for our economy.

The Impact of Higher Rates

In general, you can think of higher rates as a transfer of wealth from borrowers to lenders. If rates go up, lenders are better off; if rates go down, borrowers are better off.

Now is a great time to be a lender. If you have savings, you can plop it in a money market fund and make over 5% lending money to the U.S. government. You can make even more than that by offering riskier loans, for instance, to corporations.

On the flip side, borrowers typically don’t like higher interest rates.

From a broad economic perspective, all else equal, higher rates tend to lead to less demand for borrowing money, which then translates into less consumption and investment. If you have to pay 9% instead of 6% on an auto loan, maybe you won’t buy that car you’ve been eying.

By the same token, if a business has to pay 8% instead of 3% to borrow money, maybe it’s no longer profitable to build another factory.

Some industries are obviously more affected than others. Real estate is very interest rate sensitive. We’ve seen the residential housing market essentially come to a standstill due to high rates.

Commercial real estate has been affected as well, and there’s concerns that some commercial real estate operators could struggle to stay afloat if they’re forced to refinance their debt at high interest rates.

Similar concerns exist for many companies that borrowed heavily during the low interest rate era and who have to refinance that debt in the future at much higher rates.

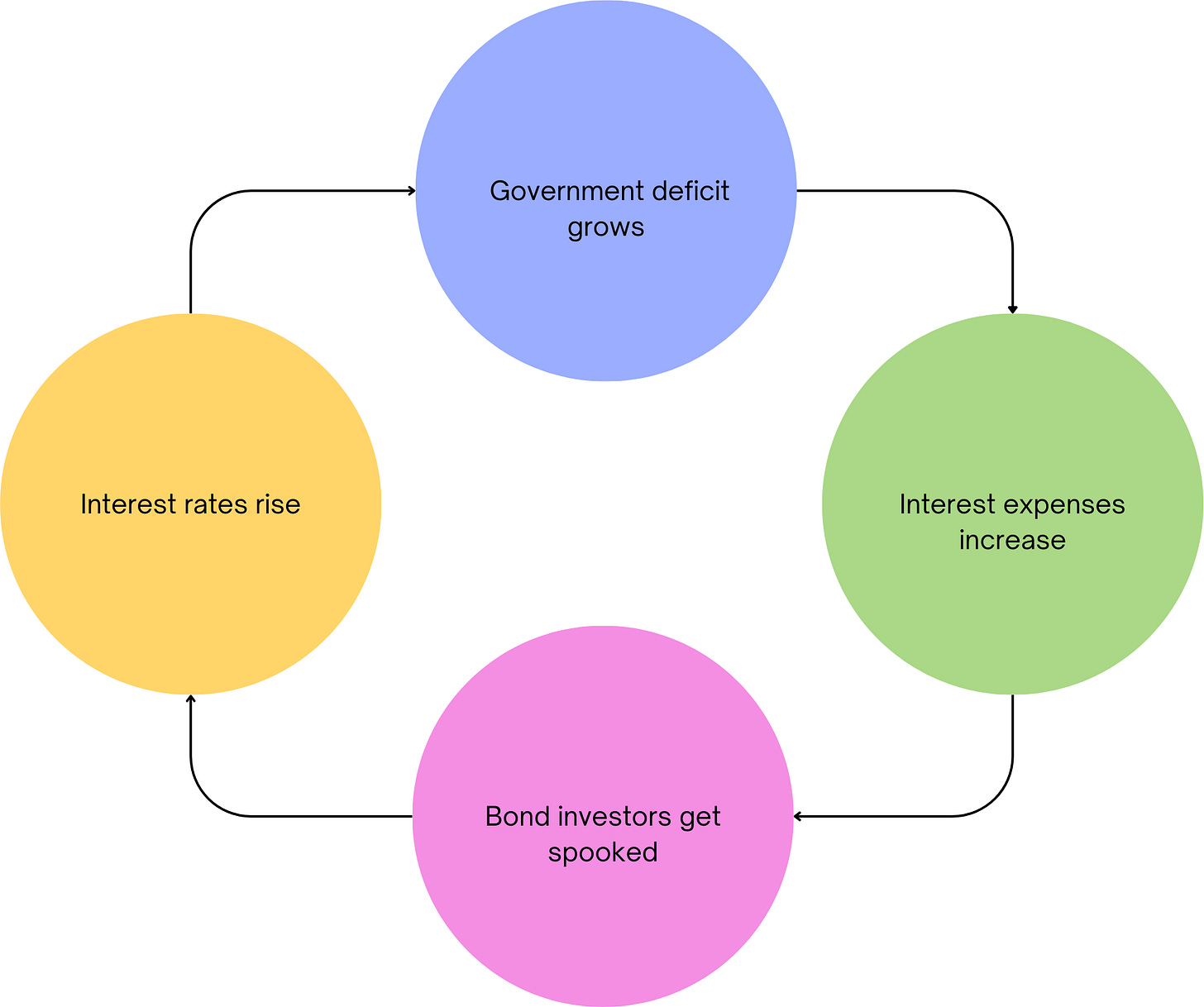

This doesn’t apply to just companies. The federal government is borrowing heavily to fund its budget deficit, and there’s worries that as it issues new debt and rolls over its old debt at higher interest rates, its interest expenses will balloon.

At some point, maybe the government’s interest expenses get so high that it spooks bond investors; causing interest rates to rise further; leading to even higher expenses for the government; which causes more interest rate increases; on and on in a vicious cycle.

That’s obviously a very gloomy scenario and confidence in the federal government’s finances would need to be shaken significantly before we ever see anything like that. But it’s something to think about if interest rates stay high, or worse, head even higher.

Another area where high interest rates have an impact is on asset prices. High interest rates make it so income received in the future is worth less today, so that weighs on the valuations of income-generating assets—things like stocks and real estate.

Good Reasons vs Bad Reasons

By now you have a sense that higher interest rates are a drag on the economy and asset prices, when you look at them in isolation.

But you have to remember, the fluctuations in interest rates that we’re seeing aren’t happening in a vacuum. They’re a reflection of several different factors, including expectations for Fed monetary policy (the fed funds rate), inflation, the federal budget deficit and economic growth.

You can think of these factors as impacting the supply and demand for bonds⁵. If the supply of bonds increases, their price goes down and interest rates go up (interest rates and bond prices move in opposite directions). On the other hand, if the demand for bonds increases, their price goes up and interest rates go down.

You can see that the supply and demand for bonds drives interest rates. And today, the interplay between the supply and demand for bonds is driving interest rates up.

That said, there’s a difference between interest rates going up for good reasons and interest rates going up for bad reasons.

A good reason would be that economic growth is strong. In that scenario, companies (and maybe even the government) borrow a lot of money to fund capital investments. So, they issue a lot of bonds, increasing the supply of bonds, and that pushes interest rates up.

But they’re happy to pay those higher rates because there are so many worthwhile, profitable investment opportunities in the economy.

If you think about our current economy, maybe all of the money being spent on A.I., clean energy, infrastructure, etc. is creating an investment boom and that’s fueling higher interest rates⁶.

On the flip side, a bad reason for rates to go up would be concerns about the sustainability of the federal government’s large budget deficits. If bond investors lose confidence in the federal government’s fiscal discipline, that could spark the vicious cycle I talked about earlier.

Inflation

Then there’s also inflation, which is a driver of interest rates as well. This one is kind of ambiguous—it could be neutral or it could be bad—it depends on if the inflation is predictable or not.

If long-term interest rates are rising because bond investors think that inflation going forward will be a little bit higher than it’s been in the recent past due to de-globalization or other factors, then that might be okay as long as that inflation is predictable and people know what to expect.

Because—I haven’t mentioned this up until now, but it’s important—it’s the real, inflation-adjusted interest rate that matters for the economy. If interest rates are 5% and inflation is 3%, then the real inflation-adjusted rate is 2% (the borrower is paying back their loan with money that is worth less over time).

You would have the same real interest rate in that scenario as when interest rates are 4% and inflation is 2%.

In both cases, the real interest rate is 2%.

So, if the nominal interest rate (the interest rate that’s not adjusted for inflation) goes up 1% because investors expect inflation to be 1% higher, that’s fine because then the nominal rate is only rising to reflect the higher rate of inflation. The real interest rate—which is the one that matters— isn’t going up.

Where you run into problems is if inflation becomes volatile and unpredictable. If prices rise 8% one year, 3% the next year and then 5% the year after that, then things become a lot more uncertain.

Investors don’t know what inflation will be from one year to the next, so they’ll most likely demand much higher interest rates to compensate them for the higher risk that they’re taking by buying bonds. In that case, the real interest rate will probably go up quite a bit, which is bad for the economy.

As you can see, the reason why interest rates are rising matters. High interest rates aren’t a bad thing if they reflect better economic growth prospects or slightly higher inflation⁷. They only start to become more of a concern if they’re a reflection of unsustainable federal budget deficits, high and unpredictable levels of inflation, and things like that.

If you consider that idea in the context of the current environment, you could say that the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note has surged in recent weeks for both good reasons and bad reasons.

The economy is much stronger than most people thought it would be—that’s a good reason. On the other hand, the federal government’s budget deficit is unusually large and there’s a lot of uncertainty about the future path for inflation—those are bad reasons.

An Uncertain Outlook

So, we’ll see how this all shakes out and where the rate on the 10-year Treasury ultimately tops out. If settles around 5%, we probably don’t need to panic, as long as inflation is under control.

Assuming inflation is 2% or 3%, that translates into a real interest rate of 2% or 3%.

Yes, that is much higher than what we saw over the past 15 years when real interest rates were around -1% to 1%, but it’s not so different than what we saw before the global financial crisis. And the economy and asset prices did pretty well in the 1990s and early 2000s, even with those higher interest rates⁸ ⁹ ¹⁰.

On the other hand, there are more bearish scenarios to consider as well. Maybe inflation remains elevated, causing nominal interest rates to keep climbing beyond 5%—to 6%, 7% or more (pushing real interest rates to 3-5%+).

I’m not sure the economy could handle that (then again, I’ve been surprised how resilient the economy has been in the face of the rate increases we’ve seen so far).

So, the bottom line is this: there’s a lot of uncertainty in the outlook for interest rates. As I said at the start of this piece, no one knows definitively whether high interest rates are here to stay.

It’s going to be months or even years before we know whether we’ve entered a new interest rate paradigm or not.

I’ll keep you posted.

¹ Reduced foreign buying of Treasuries has also been cited as a cause for higher interest rates. The evidence doesn’t back that up though

² Technical factors, like the shift in stock-bond correlations from negative to positive, have been cited as a reason for spiking rates as well

³ ”Quantitative tightening” by the Fed, where the central bank lets bonds on its balance sheet “roll off” without being replaced has acted as an effective increase in bond supply

⁴ Some have argued that low rates in the post-GFC period were caused solely by central bank monetary policy. But if that was the case and rates were artificially held down by the Fed, then we should have had runaway inflation. Instead, inflation was extremely low

⁵ Bonds in this example are a proxy for borrowing money. Obviously, there are many ways to borrow money outside of issuing bonds

⁶ By the same token, when rates were depressed following the global financial crisis, that was because the demand for borrowing money was low. Economic growth was weak and there weren’t a lot of investment opportunities

⁷ A slight rise in inflation could still be a problem if the Federal Reserve isn’t okay with it and slows the economy dramatically to get to its 2% target

⁸ There is the possibility that the economy can support a higher level of interest rates, but that a sudden surge in interest rates causes economic and financial market troubles (similar to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank)

⁹ The overall economy might hold up, but low-quality investments that were only feasible in the low-rate era could suffer if high rates are here to stay

¹⁰ For the first time in a long time, stocks are facing competition from bonds. 5% yields in Treasuries and even higher yields in corporate bonds could be attractive to some investors compared to stocks, which have delivered average returns of around 10%, but with much more volatility